Caspian Sea

| Caspian Sea | |

|---|---|

| Azerbaijani: Xəzər dənizi, Turkmen: Hazar deňizi, Kazakh: Каспий теңізі, Russian: Каспийское море, Persian: دریای کاسپین | |

| File:ISS056-E-13641 - View of Azerbaijan.jpg The Caspian Sea taken from the International Space Station, seen from the southwest | |

| Location | Eastern Europe, West Asia, and Central Asia |

| Coordinates | 42°00′N 50°30′E / 42.0°N 50.5°E |

| Type | Ancient lake, Endorheic, saline, permanent, natural |

| Primary inflows | Volga River, Ural River, Kura River, Terek River, Haraz River, Sefid-Rud |

| Primary outflows | Evaporation, Kara-Bogaz-Gol |

| Catchment area | 3,626,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Russian Federation (specifically Astrakhan Oblast, Dagestan and Kalmykia) |

| Max. length | 1,030 km (640 mi) |

| Max. width | 435 km (270 mi) |

| Surface area | 371,000 km2 (143,200 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 211 m (690 ft) |

| Max. depth | 1,025 m (3,360 ft) |

| Water volume | 78,200 km3 (18,800 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 250 years |

| Shore length1 | 7,000 km (4,300 mi) |

| Surface elevation | −28 m (−92 ft) |

| Islands | 26+ |

| Settlements | Baku (Azerbaijan), Bandar-e Anzali (Iran), Aqtau (Kazakhstan), Makhachkala (Russia), Türkmenbaşy (Turkmenistan) (see article) |

| References | [1] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea.[2][3][4] An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia, south of the fertile plains of Southern Russia in Eastern Europe, and north of the mountainous Iranian Plateau. It covers a surface area of 371,000 km2 (143,000 sq mi) (excluding the highly saline lagoon of Garabogazköl to its east), an area approximately equal to that of Japan, with a volume of 78,200 km3 (19,000 cu mi).[5] It has a salinity of approximately 1.2% (12 g/L), about a third of the salinity of average seawater. It is bounded by Kazakhstan to the northeast, Russia to the northwest, Azerbaijan to the southwest, Iran to the south, and Turkmenistan to the southeast. The name of the Caspian sea is derived from the ancient Iranic Caspi people. The sea stretches 1,200 km (750 mi) from north to south, with an average width of 320 km (200 mi). Its gross coverage is 386,400 km2 (149,200 sq mi) and the surface is about 27 m (89 ft) below sea level. Its main freshwater inflow, Europe's longest river, the Volga, enters at the shallow north end. Two deep basins form its central and southern zones. These lead to horizontal differences in temperature, salinity, and ecology. The seabed in the south reaches 1,023 m (3,356 ft) below sea level, which is the third-lowest natural non-oceanic depression on Earth after Baikal and Tanganyika lakes. Written accounts from the ancient inhabitants of its coast perceived the Caspian Sea as an ocean, probably because of its salinity and large size. With a surface area of 371,000 square kilometres (143,000 sq mi), the Caspian Sea is nearly five times as big as Lake Superior (82,000 square kilometres (32,000 sq mi)).[6] The Caspian Sea is home to a wide range of species and is famous for its caviar and oil industries. Pollution from the oil industry and dams on rivers that drain into it have harmed its ecology. It is predicted that during the 21st century, the depth of the sea will decrease by 9–18 m (30–60 ft) due to global warming and the process of desertification, leading to an ecocide.[7][8][9]

Etymology

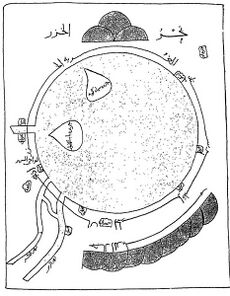

The sea's name stems from Caspi, the ancient people who lived to the southwest of the sea in Transcaucasia.[10] Strabo (died circa AD 24) wrote that "to the country of the Albanians (Caucasian Albania, not to be confused with the country of Albania) belongs also the territory called Caspiane, which was named after the Caspian tribe, as was also the sea; but the tribe has now disappeared".[11] Moreover, the Caspian Gates, part of Iran's Tehran province, may evince such people migrated to the south. The Iranian city of Qazvin shares the root of its name with this common name for the sea. The traditional and medieval Arabic name for the sea was Baḥr ('sea') Khazar, but in recent centuries the common and standard name in Arabic language has become بحر قزوين Baḥr Qazvin, the Arabized form of Caspian.[12] In modern Russian language, it is known as Russian: Каспи́йское мо́ре, Kaspiyskoye more.[13] Some Turkic ethnic groups refer to it with the Caspi(an) descriptor; in Kazakh it is called Каспий теңізі, Kaspiy teñizi, Kyrgyz: Каспий деңизи, romanized: Kaspiy deñizi, Uzbek: Kaspiy dengizi. Others refer to it as the Khazar sea: Turkmen: Hazar deňzi; Azerbaijani: Xəzər dənizi, Turkish: Hazar Denizi. In all these the first word refers to the historical Khazar Khaganate, a large empire based to the north of the Caspian Sea between the 7th and 10th centuries.[citation needed] In Iran, the lake is referred to as the Mazandaran Sea (Persian: دریای مازندران), after the historic Mazandaran Province at its southern shores.[14] Old Russian sources use the Khvalyn or Khvalis Sea (Хвалынское море / Хвалисское море) after the name of Khwarezmia.[15] Among Greeks and Persians in classical antiquity it was the Hyrcanian ocean.[16] Renaissance European maps labelled it as the Abbacuch Sea (Oronce Fine's 1531 world map), Mar de Bachu (Ortellius' 1570 map), or Mar de Sala (the Mercator 1569 world map). It was also sometimes called the Kumyk Sea[17] and Tarki Sea[18] (derived from the name of the Kumyks and their historical capital Tarki).

Basin countries

Border countries

North

East

West

South

Physical characteristics

Formation

The Caspian Sea is at its South Caspian Basin, like the Black Sea, a remnant of the ancient Paratethys Sea. Its seafloor is, therefore, a standard oceanic basalt and not a continental granite body.[19] It is estimated to be about 30 million years old,[20] and became landlocked in the Late Miocene, about 5.5 million years ago, due to tectonic uplift and a fall in sea level. The Caspian Sea was a comparatively small endorheic lake during the Pliocene, but its surface area increased fivefold around the time of the Pliocene-Pleistocene transition.[21] During warm and dry climatic periods, the landlocked sea almost dried up, depositing evaporitic sediments like halite that were covered by wind-blown deposits and were sealed off as an evaporite sink when cool, wet climates refilled the basin. (Comparable evaporite beds underlie the Mediterranean.) Due to the current inflow of fresh water in the north, the Caspian Sea water is almost fresh in its northern portions, getting more brackish toward the south. It is most saline on the Iranian shore, where the catchment basin contributes little flow.[22] Currently, the mean salinity of the Caspian is one third that of Earth's oceans. The Garabogazköl lagoon, which dried up when water flow from the main body of the Caspian was blocked in the 1980s but has since been restored, routinely exceeds oceanic salinity by a factor of 10.[23]

Geography

The Caspian Sea is the largest inland body of water in the world by area and accounts for 40–44% of the total lake waters of the world,[24] and covers an area larger than Germany. The coastlines of the Caspian are shared by Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan. The Caspian is divided into three distinct physical regions: the Northern, Middle, and Southern Caspian.[25] The Northern–Middle boundary is the Mangyshlak Threshold, which runs through Chechen Island and Cape Tiub-Karagan. The Middle–Southern boundary is the Apsheron Threshold, a sill of tectonic origin between the Eurasian continent and an oceanic remnant,[26] that runs through Zhiloi Island and Cape Kuuli.[27] The Garabogazköl Bay is the saline eastern inlet of the Caspian, which is part of Turkmenistan and at times has been a lake in its own right due to the isthmus that cuts it off from the Caspian. Differences between the three regions are dramatic. The Northern Caspian only includes the Caspian shelf,[28] and is very shallow; it accounts for less than 1% of the total water volume with an average depth of only 5–6 m (16–20 ft). The sea noticeably drops off towards the Middle Caspian, where the average depth is 190 m (620 ft).[27] The Southern Caspian is the deepest, with oceanic depths of over 1,000 m (3,300 ft), greatly exceeding the depth of other regional seas, such as the Persian Gulf. The Middle and Southern Caspian account for 33% and 66% of the total water volume, respectively.[25] The northern portion of the Caspian Sea typically freezes in the winter, and in the coldest winters ice forms in the south as well.[29]

Over 130 rivers provide inflow to the Caspian, the Volga River being the largest. A second affluent, the Ural River, flows in from the north, and the Kura River from the west. In the past, the Amu Darya (Oxus) of Central Asia in the east often changed course to empty into the Caspian through a now-desiccated riverbed called the Uzboy River, as did the Syr Darya farther north. The Caspian has several small islands, primarily located in the north with a collective land area of roughly 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi). Adjacent to the North Caspian is the Caspian Depression, a low-lying region 27 m (89 ft) below sea level. The Central Asian steppes stretch across the northeast coast, while the Caucasus mountains hug the western shore. The biomes to both the north and east are characterized by cold, continental deserts. Conversely, the climate to the southwest and south are generally warm with uneven elevation due to a mix of highlands and mountain ranges; the drastic changes in climate alongside the Caspian have led to a great deal of biodiversity in the region.[23]

The Caspian Sea has numerous islands near the coasts, but none in the deeper parts of the sea. Ogurja Ada is the largest island. The island is 37 km (23 mi) long, with gazelles roaming freely on it. In the North Caspian, the majority of the islands are small and uninhabited, like the Tyuleniy Archipelago, an Important Bird Area (IBA).

Climate

The climate of the Caspian Sea is variable, with the cold desert climate (BWk), cold semi-arid climate (BSk), and humid continental climate (Dsa, Dfa) being present in the northern portions of the Caspian Sea, while the Mediterranean climate (Csa) and humid subtropical climate (Cfa) are present in the southern portions of the Caspian Sea.

Hydrology

The Caspian has characteristics common to both seas and lakes. It is often listed as the world's largest lake, although it is not freshwater: the 1.2% salinity classes it with brackish water bodies. It contains about 3.5 times as much water, by volume, as all five of North America's Great Lakes combined. The Volga River (about 80% of the inflow) and the Ural River discharge into the Caspian Sea, but it has no natural outflow other than by evaporation. Thus the Caspian ecosystem is a closed basin, with its own sea level history that is independent of the eustatic level of the world's oceans. The sea level of the Caspian has fallen and risen, often rapidly, many times over the centuries. Some Russian historians, such as Lev Gumilev, claim that the rising of the Caspian in the 10th century caused the coastal towns of Khazaria to flood, resulting in the Khazars losing approximately two-thirds of their territory due to flooding.[30] Over the centuries, Caspian Sea levels have changed in synchrony with the estimated discharge of the Volga, which in turn depends on rainfall levels in its vast catchment basin. Precipitation is related to variations in the amount of North Atlantic depressions that reach the interior, and they in turn are affected by cycles of the North Atlantic oscillation. Thus levels in the Caspian Sea relate to atmospheric conditions in the North Atlantic, thousands of kilometres to the northwest.[31] The last short-term sea-level cycle started with a sea-level fall of 3 m (10 ft) from 1929 to 1977, followed by a rise of 3 m (10 ft) from 1977 until 1995. Since then smaller oscillations have taken place.[32] A study by the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences estimated that the level of the sea was dropping by more than six centimetres per year due to increased evaporation due to rising temperatures caused by climate change.[33]

Environmental degradation

The Volga River, the longest river in Europe, drains 20% of the European land area and is the source of 80% of the Caspian's inflow. Heavy development in its lower reaches has caused numerous unregulated releases of chemical and biological pollutants. The UN Environment Programme warns that the Caspian "suffers from an enormous burden of pollution from oil extraction and refining, offshore oil fields, radioactive wastes from nuclear power plants and huge volumes of untreated sewage and industrial waste introduced mainly by the Volga River".[33] The magnitude of fossil fuel extraction and transport activity in the Caspian also poses a risk to the environment. The island of Vulf off Baku, for example, has suffered ecological damage as a result of the petrochemical industry; this has significantly decreased the number of species of marine birds in the area. Existing and planned oil and gas pipelines under the sea further increase the potential threat to the environment.[34] The high concentration of mud volcanoes under the Caspian Sea were thought to be the cause of a fire that broke out 75 kilometers from Baku on July 5, 2021. The State oil company of Azerbaijan SOCAR said preliminary information indicated it was a mud volcano which spewed both mud and flammable gas.[35] It is calculated that during the 21st century, the water level of the Caspian Sea will decrease by 9–18 m (30–60 ft) due to the acceleration of evaporation due to global warming and the process of desertification, causing an ecocide.[7][8][9][36] On October 23, 2021, Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed the Protocol for the Protection of the Caspian Sea against Pollution from Land-based Sources in order to ensure better protection for the biodiversity of the Caspian Sea.[37]

Flora and fauna

Flora

The rising level of the Caspian Sea between 1995 and 1996 reduced the number of habitats for rare species of aquatic vegetation. This has been attributed to a general lack of seeding material in newly formed coastal lagoons and water bodies.[38][39] Many rare and endemic plant species of Russia are associated with the tidal areas of the Volga delta and riparian forests of the Samur River delta. The shoreline is also a unique refuge for plants adapted to the loose sands of the Central Asian Deserts. The principal limiting factors to successful establishment of plant species are hydrological imbalances within the surrounding deltas, water pollution, and various land reclamation activities. The water level change within the Caspian Sea is an indirect reason for which plants may not get established. These affect aquatic plants of the Volga Delta, such as Aldrovanda vesiculosa and the native Nelumbo caspica. About 11 plant species are found in the Samur River delta, including the unique liana forests that date back to the Tertiary period.[40] Since 2019 UNESCO has admitted the lush Hyrcanian forests of Mazandaran, Iran as World Heritage Site under category (ix).[41]

Fauna

The Caspian turtle (Mauremys caspica), although found in neighboring areas, is a wholly freshwater species. The zebra mussel is native to the Caspian and Black Sea basins, but has become an invasive species elsewhere, when introduced. The area has given its name to several species, including the Caspian gull and the Caspian tern. The Caspian seal (Pusa caspica) is the only aquatic mammal endemic to the Caspian Sea, being one of very few seal species that live in inland waters, but it is different from those inhabiting freshwaters due to the hydrological environment of the sea. A century ago the Caspian was home to more than one million seals. Today, fewer than 10% remain.[33] Archeological studies of Gobustan Rock Art have identified what may be oceanic species including cetaceans from baleen whales to dolphins,[43][44] and auks most likely Brunnich's Guillemot,[43][45] although the rock art on Kichikdash Mountain which is assumed to depict either a beaked whale or a dolphin,[43][45] it may represent the famous beluga sturgeon instead due to its size (430 cm in length). These petroglyphs may suggest potential presences of oceanic faunas in the Caspian Sea presumably until the Quaternary or even the last glacial period or antiquity due to historic marine inflow between the current Caspian Sea and either the Arctic Ocean or North Sea, or the Black Sea. This is supported by the existences of current endemic, oceanic species such as lagoon cockles which was genetically identified to originate in the Caspian and Black Seas regions.[43][46] The sea's basin (including associated waters such as rivers) has 160 native species and subspecies of fish in more than 60 genera.[42] About 62% of the species and subspecies are endemic, as are 4–6 genera (depending on taxonomic treatment). The lake proper has 115 natives, including 73 endemics (63.5%).[42] Among the more than 50 genera in the lake proper, 3–4 are endemic: Anatirostrum, Caspiomyzon, Chasar (often included in Ponticola) and Hyrcanogobius.[42] By far the most numerous families in the lake proper are gobies (35 species and subspecies), cyprinids (32) and clupeids (22). Two particularly rich genera are Alosa with 18 endemic species/subspecies and Benthophilus with 16 endemic species.[42] Other examples of endemics are four species of Clupeonella, Gobio volgensis, two Rutilus, three Sabanejewia, Stenodus leucichthys, two Salmo, two Mesogobius and three Neogobius.[42] Most non-endemic natives are either shared with the Black Sea basin or widespread Palearctic species such as crucian carp, Prussian carp, common carp, common bream, common bleak, asp, white bream, sunbleak, common dace, common roach, common rudd, European chub, sichel, tench, European weatherfish, wels catfish, northern pike, burbot, European perch and zander.[42] Almost 30 non-indigenous, introduced fish species have been reported from the Caspian Sea, but only a few have become established.[42] Six sturgeon species, the Russian, bastard, Persian, sterlet, starry and beluga, are native to the Caspian Sea.[42] The last of these is arguably the largest freshwater fish in the world. The sturgeon yield roe (eggs) that are processed into caviar. Overfishing has depleted a number of the historic fisheries.[47] In recent years, overfishing has threatened the sturgeon population to the point that environmentalists advocate banning sturgeon fishing completely until the population recovers. The high price of sturgeon caviar – more than 1,500 Azerbaijani manats[33] (US$880 as of April 2019[update]) per kilo – allows fishermen to afford bribes to ensure the authorities look the other way, making regulations in many locations ineffective.[48] Caviar harvesting further endangers the fish stocks, since it targets reproductive females.

Reptiles native to the region include the spur-thighed tortoise (Testudo graeca buxtoni) and Horsfield's tortoise.

- The Asiatic cheetah used to occur in the Trans-Caucasus and Central Asia, but is today restricted to Iran.[49][50]

- The Asiatic lion used to occur in the Trans-Caucasus, Iran, and possibly the southern part of Turkestan.[49][50]

- The Caspian tiger used to occur in northern Iran, the Caucasus and Central Asia.[49][50]

- The endangered Persian leopard is found in Iran, the Caucasus and Central Asia.[49][50]

History

Geology

The main geologic history locally had two stages. The first is the Miocene, determined by tectonic events that correlate with the closing of the Tethys Sea. The second is the Pleistocene noted for its glaciation cycles and the full run of the present Volga. During the first stage, the Tethys Sea had evolved into the Sarmatian Lake, that was created from the modern Black Sea and south Caspian, when the collision of the Arabian peninsula with West Asia pushed up the Kopet Dag and Caucasus Mountains, lasting south and west limits to the basin. This orogenic movement was continuous, while the Caspian was regularly disconnected from the Black Sea. In the late Pontian stage, a mountain arch rose across the south basin and divided it into the Khachmaz and Lankaran Lakes (or early Balaxani). The period of restriction to the south basin was reversed during the Akchagylian – the lake became more than three times its size today and took again the first of a series of contacts with the Black Sea and Aral Sea. A recession of Lake Akchagyl completed stage one.[51]

Early settlement nearby

The earliest hominid remains found around the Caspian Sea are from Dmanisi dating back to around 1.8 Ma and yielded a number of skeletal remains of Homo erectus or Homo ergaster. More later evidence for human occupation of the region came from a number of caves in Georgia and Azerbaijan such as Kudaro and Azykh Caves. There is evidence for Lower Palaeolithic human occupation south of the Caspian from western Alburz. These are Ganj Par and Darband Cave sites. Neanderthal remains also have been discovered at a cave in Georgia. Discoveries in the Hotu cave and the adjacent Kamarband cave, near the town of Behshahr, Mazandaran south of the Caspian in Iran, suggest human habitation of the area as early as 11,000 years ago.[52][53] Ancient Greeks focused on the civilization on the south shore – they call it the (H)yr(c/k)anian Sea (Ancient Greek: Υρκανία θάλαττα,[54] with sources noting the latter word was evolving then to today's Thelessa: late Ancient Greek: θάλασσα).[55] Hafiz-i Abru, a fourteenth century Timurid Empire geographer, recorded that the destruction of the Oxus river dam and irrigation works diverted the river flow towards the Caspian Sea, which caused the Aral sea to nearly disappear.[56][57]

Chinese maximal limit

Later, in the Tang dynasty (618–907), the sea was the western limit of the Chinese Empire.[58][59][dubious – discuss]

Fossil fuel

The area is rich in fossil fuels. Oil wells were being dug in the region as early as the 10th century to reach oil "for use in everyday life, both for medicinal purposes and for heating and lighting in homes".[60] By the 16th century, Europeans were aware of the rich oil and gas deposits locally. English traders Thomas Bannister and Jeffrey Duckett described the area around Baku as "a strange thing to behold, for there issueth out of the ground a marvelous quantity of oil, which serveth all the country to burn in their houses. This oil is black and is called nefte. There is also by the town of Baku, another kind of oil which is white and very precious [i.e., petroleum]."[61] Today, oil and gas platforms abound along the edges of the sea.[62]

During the rule of Peter I the Great, Fedor I. Soimonov was a pioneering explorer of the sea. He was a hydrographer who charted and greatly expanded knowledge of the sea. He drew a set of four maps and wrote Pilot of the Caspian Sea, the first lengthy report and modern maps. These were published in 1720 by the Russian Academy of Sciences.[63]

Cities

Ancient

- Hyrcania, ancient state in the north of Iran

- Sari, Mazandaran Province of Iran

- Anzali, Gilan Province of Iran

- Astara, Gilan Province of Iran

- Astarabad, Golestan Province of Iran

- Tamisheh, Golestan Province of Iran

- Atil, Khazaria

- Khazaran

- Baku, Azerbaijan

- Derbent, Dagestan, Russia

- Xacitarxan, modern-day Astrakhan

Modern

- Iran:

- Azerbaijan:

- Kazakhstan:

- Russia:

- Turkmenistan:

- Türkmenbaşy (formerly Krasnovodsk)

- Hazar (formerly Çeleken)

- Esenguly

- Garabogaz (formerly Bekdaş)

Economy

Countries in the Caspian region, particularly Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, have high-value natural-resource-based economies, where the oil and gas compose more than 10 percent of their GDP and 40 percent of their exports.[64] All the Caspian region economies are highly dependent on this type of mineral wealth. The world energy markets were influenced by Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, as they became strategically crucial in this sphere, thus attracting the largest share of foreign direct investment (FDI). All of the countries are rich in solar energy and harnessing potential, with the highest rainfall much less than the mountains of central Europe in the mountains of the west, which are also rich in hydroelectricity sources. Iran has high fossil fuel energy potential. It has reserves of 137.5 billion barrels of crude oil, the fourth largest in the world, producing around four million barrels a day. Iran has an estimated 988.4 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, around 16 percent of world reserves, thus key to current paradigms in global energy security.[64] Russia's economy ranks as the twelfth largest by nominal GDP and sixth largest by purchasing power parity in 2015.[65] Russia's extensive mineral and energy resources are the largest such reserves in the world,[66] making it the second leading producer of oil and natural gas globally.[67] Caspian littoral states join efforts to develop infrastructure, tourism and trade in the region. The first Caspian Economic Forum was convened on August 12, 2019, in Turkmenistan and brought together representatives of Kazakhstan, Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran and that state. It hosted several meetings of their ministers of economy and transport.[68] The Caspian countries develop robust cooperation in the tech and digital field as part of the Caspian Digital Hub. The project helps expand data transmission capabilities in Kazakhstan as well as data transit capabilities between Asia and Europe. The project generated interest from investors from all over the world, including the UK.[69]

Oil and gas

The Caspian Sea region presently is a significant, but not major, supplier of crude oil to world markets, based upon estimates by BP Amoco and the U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy. The region output about 1.4–1.5 million barrels per day plus natural gas liquids in 2001, 1.9% of total world output. More than a dozen countries output more than this top figure. Caspian region production has been higher, but waned during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan accounts for 55% and Azerbaijan for about 20% of the states' oil output.[70]

The world's first offshore wells and machine-drilled wells were made in Bibi-Heybat Bay, near Baku, Azerbaijan. In 1873, exploration and development of oil began in some of the largest fields known to exist in the world at that time on the Absheron Peninsula near the villages of Balakhanli, Sabunchi, Ramana, and Bibi Heybat. Total recoverable reserves were more than 500 million tons. By 1900, Baku had more than 3,000 oil wells, 2,000 of which were producing at industrial levels. By the end of the 19th century, Baku became known as the "black gold capital", and many skilled workers and specialists flocked to the city. By the beginning of the 20th century, Baku was the center of the international oil industry. In 1920, when the Bolsheviks captured Azerbaijan, all private property, including oil wells and factories, was confiscated. Rapidly the republic's oil industry came under the control of the Soviet Union. By 1941, Azerbaijan was producing a record 23.5 million tons of oil per year – its Baku region output was nearly 72 percent of the Soviet Union's oil.[60] In 1994, the "Contract of the Century" was signed, heralding extra-regional development of the Baku oil fields. The large Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline conveys Azeri oil to the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan and opened in 2006. The Vladimir Filanovsky oil field in the Russian section of the body of water was discovered in 2005. It is reportedly the largest found in 25 years. It was announced in October 2016 that Lukoil would start production from it.[71]

Transport

Baku has the main moorings of all large vessels, such as oil tankers, in Azerbaijan. It is the largest port of the Caspian Sea. The port (and tankers) have access to the oceans along the Caspian Sea–Volga–Don Canal, and the Don–Sea of Azov. A northern alternate is the Volga–Baltic (a sea which has a connection to the North Sea of the Atlantic, as the White Sea does via the White Sea-Baltic canal). Baku Sea Trade Port and Caspian Shipping Company CJSC, have a big role in the sea transportation of Azerbaijan. The Caspian Sea Shipping Company CJSC has two fleets plus shipyards. Its transport fleet has 51 vessels: 20 tankers, 13 ferries, 15 universal dry cargo vessels, 2 Ro-Ro vessels, as well as 1 technical vessel and 1 floating workshop. Its specialized fleet has 210 vessels: 20 cranes, 25 towing and supplying vehicles, 26 passenger, two pipe-laying, six fire-fighting, seven engineering-geological, two diving and 88 auxiliary vessels.[72] The Caspian Sea Shipping Company of Azerbaijan, which acts as a liaison in the Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA), simultaneously with the transportation of cargo and passengers in the Trans-Caspian direction, also performs work to fully ensure the processes of oil and gas production at sea. In the 19th century, the sharp increase in oil production in Baku gave a huge impetus to the development of shipping in the Caspian Sea, and as a result, there was a need to create fundamentally new floating facilities for the transportation of oil and oil products.[73]

Political issues

Many of the islands along the Azerbaijani coast retain great geopolitical and economic importance for demarcation-line oil fields relying on their national status. Bulla Island, Pirallahı Island, and Nargin, which is still used as a former Soviet base and is the largest island in the Baku bay, hold oil reserves. The collapse of the Soviet Union allowed the market opening of the region. This led to intense investment and development by international oil companies. In 1998, Dick Cheney commented that "I can't think of a time when we've had a region emerge as suddenly to become as strategically significant as the Caspian."[74] A key problem to further local development is arriving at precise, agreed demarcation lines among the five littoral states. The current disputes along Azerbaijan's maritime borders with Turkmenistan and Iran could impinge future development. Much controversy currently exists over the proposed Trans-Caspian oil and gas pipelines. These projects would allow Western markets easier access to Kazakh oil and, potentially, Uzbek and Turkmen gas as well. Russia officially opposes the project on environmental grounds.[75] However, analysts note that the pipelines would bypass Russia completely, thereby denying the country valuable transit fees, as well as destroying its current monopoly on westward-bound hydrocarbon exports from the region.[75] Recently, both Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have expressed their support for the Trans-Caspian Pipeline.[76] Leaked U.S. diplomatic cables revealed that BP covered up a gas leak and blowout incident in September 2008 at an operating gas field in the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshi area of the Azerbaijan Caspian Sea.[77][78]

Territorial status

Coastline

Five states are located along about 4,800 km (3,000 mi) of Caspian coastline. The length of the coastline of these countries:[79]

- Kazakhstan – 1,422 km (884 mi)

- Turkmenistan – 1,035 km (643 mi)

- Iran – 865 km (537 mi)

- Azerbaijan – 813 km (505 mi)

- Russia – 692 km (430 mi)

Negotiations

The nations of Iran & the USSR split the Caspian sea's surface 50/50 and the sea's volume 75/25 with Iran getting more, between themselves in 1931. In 2000, negotiations as to the demarcation of the sea had been going on for nearly a decade among all the states bordering it. Whether it was by law a sea, a lake, or an agreed hybrid, the decision would set the demarcation rules and was heavily debated.[80] Access to mineral resources (oil and natural gas), access for fishing, and access to international waters (through Russia's Volga river and the canals connecting it to the Black Sea and Baltic Sea) all rest on the negotiations' outcome. Access to the Volga is key for market efficiency and economic diversity of the landlocked states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. This concerns Russia as more traffic seeks to use – and at some points congest – its inland waterways. If the body of water is, by law, a sea, many precedents and international treaties oblige free access to foreign vessels. If it is a lake there are no such obligations. Resolving and improving some environmental issues properly rests on the status and borders issue. All five Caspian littoral states maintain naval forces on the sea.[81]

According to a treaty signed between Iran and the Soviet Union, the sea is technically a lake and was divided into two sectors (Iranian and Soviet), but the resources (then mainly fish) were commonly shared. The line between the two sectors was considered an international border in a common lake, like Lake Albert. The Soviet sector was sub-divided into the four littoral republics' administrative sectors. Russia, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan have bilateral agreements with each other based on median lines. Because of their use by the three nations, median lines seem to be the most likely method of delineating territory in future agreements. However, Iran insists on a single, multilateral agreement among the five nations (aiming for a one-fifth share). Azerbaijan is at odds with Iran over some of the sea's oil fields. Occasionally, Iranian patrol boats have fired at vessels sent by Azerbaijan for exploration into the disputed region. There are similar tensions between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan (the latter claims that the former has pumped more oil than agreed from a field, recognized by both parties as shared). The Caspian littoral states' meeting in 2007 signed an accord that only allows littoral-state flag-bearing ships to enter the sea.[82][failed verification] Negotiations among the five states ebbed and flowed, from about 1990 to 2018. Progress was notable in the fourth Caspian Summit held in Astrakhan in 2014.[83]

Caspian Summit

The Caspian Summit is a head of state-level meeting of the five littoral states.[84] The fifth Caspian Summit took place on August 12, 2018, in the Kazakh port city of Aktau.[84] The five leaders signed the 'Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea'.[85] Representatives of the Caspian littoral states held a meeting in the capital of Kazakhstan on September 28, 2018, as a follow-up to the Aktau Summit. The conference was hosted by the Kazakh Ministry of Investment and Development. The participants in the meeting agreed to host an investment forum for the Caspian region every two years.[86]

Convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea

The five littoral states build consensus on legally binding governance of the Caspian Sea through Special Working Groups of a Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea.[87] In advance of a Caspian Summit, the 51st Special Working Group took place in Astana in May 2018 and found consensus on multiple agreements: Agreements on cooperation in the field of transport; trade and economic cooperation; prevention of incidents on the sea; combating terrorism; fighting against organized crime; and border security cooperation.[88] The convention grants jurisdiction over 24 km (15 mi) of territorial waters to each neighboring country, plus an additional 16 km (10 mi) of exclusive fishing rights on the surface, while the rest is international waters. The seabed, on the other hand, remains undefined, subject to bilateral agreements between countries. Thus, the Caspian Sea is legally neither fully a sea nor a lake.[89] While the convention addresses caviar production, oil and gas extraction, and military uses, it does not touch on environmental issues.[33]

Crossborder inflow

UNECE recognizes several rivers that cross international borders which flow into the Caspian Sea.[90] These are:

| River | Countries |

|---|---|

| Atrek River | Iran, Turkmenistan |

| Kura River | Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Turkey |

| Ural River | Kazakhstan, Russia |

| Samur River | Azerbaijan, Russia |

| Sulak River | Georgia, Russia |

| Terek River |

Transportation

Although the Caspian Sea is endorheic, its main tributary, the Volga, is connected by important shipping canals with the Don River (and thus the Black Sea) and with the Baltic Sea, with branch canals to Northern Dvina and to the White Sea. Another Caspian tributary, the Kuma River, is connected by an irrigation canal with the Don basin as well. Scheduled ferry services (including train ferries) across the sea chiefly are between:

- Türkmenbaşy in Turkmenistan, (formerly Krasnovodsk) and Baku.

- Aktau, Kazakhstan and Baku.

- Cities in Iran and Russia (chiefly for cargo.)

Canals

As an endorheic basin, the Caspian Sea basin has no natural connection with the ocean. Since the medieval period, traders reached the Caspian via a number of portages that connected the Volga and its tributaries with the Don River (which flows into the Sea of Azov) and various rivers that flow into the Baltic Sea. Primitive canals connecting the Volga Basin with the Baltic were constructed as early as the early 18th century. Since then, a number of canal projects have been completed. The two modern canal systems that connect the Volga Basin, and hence the Caspian Sea, with the ocean are the Volga–Baltic Waterway and the Volga–Don Canal. The proposed Pechora–Kama Canal was a project that was widely discussed between the 1930s and 1980s. Shipping was a secondary consideration. Its main goal was to redirect some of the water of the Pechora River (which flows into the Arctic Ocean) via the Kama River into the Volga. The goals were both irrigation and the stabilization of the water level in the Caspian, which was thought to be falling dangerously fast at the time. During 1971, some peaceful nuclear construction experiments were carried out in the region by the U.S.S.R. In June 2007, in order to boost his oil-rich country's access to markets, Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev proposed a 700 km (435 mi) link between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. It is hoped that the "Eurasia Canal" (Manych Ship Canal) would transform landlocked Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries into maritime states, enabling them to significantly increase trade volume. Although the canal would traverse Russian territory, it would benefit Kazakhstan through its Caspian Sea ports. The most likely route for the canal, the officials at the Committee on Water Resources at Kazakhstan's Agriculture Ministry say, would follow the Kuma–Manych Depression, where currently a chain of rivers and lakes is already connected by an irrigation canal (the Kuma–Manych Canal). Upgrading the Volga–Don Canal would be another option.[91]

See also

- Caspians

- Caspian languages

- Caspian Sea Monster

- Baku oil fields

- Epoch of Extreme Inundations

- Eurasia Canal

- Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea

- Iranrud

- Shah Deniz gas field

- South Caucasus Pipeline

- Southern Gas Corridor

- Tengiz Field

- Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline

- Trans-Caspian Oil Transport System

- Volga–Don Canal

- Wildlife of Azerbaijan

- Wildlife of Iran

- Wildlife of Kazakhstan

- Wildlife of Turkmenistan

- Wildlife of Russia

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 van der Leeden, Troise, and Todd, eds., The Water Encyclopedia. Second Edition. Chelsea F.C., MI: Lewis Publishers, 1990, p. 196.

- ↑ "Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea". President Of Russia. 12 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ↑ "Is the Caspian a sea or a lake?". The Economist. 16 August 2018. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ↑ Zimnitskaya, Hanna; von Geldern, James (1 January 2011). "Is the Caspian Sea a sea; and why does it matter?". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 2 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2010.10.009. ISSN 1879-3665. S2CID 154951201.

- ↑ Leong, Goh Cheng (27 October 1995). Certificate Physics And Human Geography; Indian Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-562816-6. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ "Great Lakes – Physical Facts". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dumont, Henri (October 1995). "Ecocide in the Caspian Sea". Nature. 377 (6551): 673–674. Bibcode:1995Natur.377..673D. doi:10.1038/377673a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4363852.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wesselingh, Frank; Lattuada, Matteo (23 December 2020). "The Caspian Sea is set to fall by 9 metres or more this century – an ecocide is imminent". The Conversation. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Prange, Matthias; Wilke, Thomas; Wesselingh, Frank P. (2020). "The other side of sea level change". Communications Earth & Environment. 1 (1): 69. Bibcode:2020ComEE...1...69P. doi:10.1038/s43247-020-00075-6. S2CID 229357523.

- ↑ Caspian Sea Archived 2008-01-07 at the Wayback Machine in Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Strabo. Geography. 11.3.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "موضوع : بررسی تطبیقی رژیم حقوقی بزگترین دریاچه های جهان و دریای خزر /کسپین/نام های دریاچه خزر | پژوهشهای ایرانی.دریای پارس" [Topic: Comparative study of the legal regime of the world's largest lakes and the Caspian Sea / Caspian / Caspian Lake names | Iranian researches. Pars sea]. parssea.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ Iran (5th ed., 2008), by Andrew Burke and Mark Elliott, p. 28 Archived 2011-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, Lonely Planet Publications, ISBN 978-1-74104-293-1.

- ↑ Zonn, I.S.; Kosarev, A.N.; Glantz, M.; Kostianoy, A.G. (2010). The Caspian Sea Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia of Seas. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-642-11524-0. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ↑ Max Vasmer, Etimologicheskii slovar' russkogo yazyka, Vol. IV (Moscow: Progress, 1973), p. 229.

- ↑ Hyrcania Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. www.livius.org. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ↑ Абдулгаффар Кырыми. Умдет ал-ахбар. Книга 2: Перевод. Серия «Язма Мирас. Письменное Наследие. (tr. "Abdulgaffar Crimea. Umdet al-ahbar. Book 2: Translation. Series "Written Heritage. Written Heritage.") Textual Heritage». Вып. 5 / Пер. с османского Ю. Н. Каримовой, И. М. Миргалеева; общая и научная редакция, предисловие и комментарии И. М. Миргалеева. — Казань: Институт истории им. Ш. Марджани АН РТ, 2018. — 200 с

- ↑ Гусейнов Г.-Р., "Султан-Мут и западные пределы кумыкского государства", материалы научной конференции, (tr. " "Sultan-Mut and the western limits of the Kumyk state", materials of the scientific conference") journal Средневековые тюрко-татарские государства, 2009

- ↑ Kaz’min, V. G.; Verzhbitskii, E. V. (2011). "Age and origin of the South Caspian Basin". Oceanology. 51 (1). Pleiades Publishing Ltd: 131–140. Bibcode:2011Ocgy...51..131K. doi:10.1134/s0001437011010073. ISSN 0001-4370. S2CID 129203844.

- ↑ Caspian Sea: Largest Inland Body of Water - Live Science

- ↑ Van Baak, Christiaan G. C.; Grothe, Arjen; Richards, Keith; Stoica, Marius; Aliyeva, Elmira; Davies, Gareth R.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Krijgsman, Wout (March 2019). "Flooding of the Caspian Sea at the intensification of Northern Hemisphere Glaciations". Global and Planetary Change. 174: 153–163. Bibcode:2019GPC...174..153V. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.01.007. hdl:1871.1/00574e4b-fd93-4b99-8364-ff5e466c9c2d. S2CID 134219493. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ↑ "Sea Facts". Casp Info. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Caspian Sea – Background". Caspian Environment Programme. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Caspian Sea". Iran Gazette. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hooshang Amirahmadi (2000). The Caspian Region at a Crossroad: Challenges of a New Frontier of Energy and Development. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-0-312-22351-9. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Khain V.E. Gadjiev A.N. Kengerli T.N. (2007). "Tectonic origin of the Apsheron Threshold in the Caspian Sea". Doklady Earth Sciences. 414 (1): 552–556. Bibcode:2007DokES.414..552K. doi:10.1134/S1028334X07040149. S2CID 129017738.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Henri J. Dumont; Tamara A. Shiganova; Ulrich Niermann (2004). Aquatic Invasions in the Black, Caspian, and Mediterranean Seas. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-1869-5. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ A. G. Kostianoi and A. Kosarev (2005). The Caspian Sea Environment. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-540-28281-5. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ "News Azerbaijan". ann.az. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Gumilev, Lev Nikolayevich (1967). "New Data On The History Of The Khazars" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae: 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2018.

- ↑ "Temperature and precipitation in the Caspian Sea Region | GRID-Arendal". www.grida.no. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Caspian Sea Level Project Site". Caspage.citg.tudelft.nl. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 "Caviar pool drains dry as Caspian Sea slides towards catastrophe". The Nation. Bangkok. Agence France-Presse. 18 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ↑ "Caspian Environment Programme". caspianenvironment.org. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Azerbaijan Investigates Large Fire In Caspian Sea". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 5 July 2021. Archived from the original on 5 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ Times, The Moscow (25 December 2020). "Scientists Sound the Alarm Over Fast-Shrinking Caspian Sea". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ↑ November 2021, Assel Satubaldina in Central Asia on 3 (3 November 2021). "President Tokayev Pledges to Better Protect Caspian Sea Biodiversity by Signing Caspian Sea Protection Protocol". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Caspian Sea Biodiversity Project - Biodiversity Report". www.zin.ru. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ Grillo, Oscar; Venora, Gianfranco (16 December 2011). Ecosystems Biodiversity. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-953-307-417-7. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ "Western Asia: Along the coast of the Caspian Sea in Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "Hyrcanian Forests". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 42.8 Naseka, A.M. and Bogutskaya, N.G. (2009). "Fishes of the Caspian Sea: zoogeography and updated check-list". Zoosystematica Rossica 18(2): 295–317.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Gallagher, Ronnie (2011). "The Ice Age Rise and Fall of the Ponto Caspian: Ancient Mariners and the Asiatic Mediterranean". Stratigraphy and Sedimentology of Oil-gas Basins (pp. 48-68) on Academia.edu. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ↑ Фараджева, Малахат (2015). "Культурно-исторический контекст археологического комплекса Гобустан". Российская Археология (4): 50–63. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019 – via Acedemia.edu.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Gobustan Petroglyphs – Subject Matter". The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Gobustan Petroglyphs – Methods & Chronology". The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. "Overfishing". Encyclopedia of Earth. eds. Sidney Draggan and Cutler Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

- ↑ "Fishing Prospects". Iran Daily. 14 January 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Heptner, V.G., Sludskij, A.A. (1992) [1972]. Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 1–732. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Humphreys, P., Kahrom, E. (1999). Lion and Gazelle: The Mammals and Birds of Iran Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Images Publishing, Avon.

- ↑ Dumont, H. J. (22 December 2003). "The Caspian Lake: History, biota, structure, and function". Limnology and Oceanography. 43 (1): 44–52. Bibcode:1998LimOc..43...44D. doi:10.4319/lo.1998.43.1.0044. ISSN 0024-3590.

- ↑ "Major Monuments" Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Iranair.com. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ↑ "Safeguarding Caspian Interests". Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2016.. iran-daily.com (2006-11-26)

- ↑ "Strabo, Geography, § 2.5.14". Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ↑ "Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography, §132". Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ↑ Alan Mikhail (2013). "6". Water on Sand Environmental Histories of the Middle East and North Africa (Paperback). OUP USA. p. 152. ISBN 9780199768660. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

... Sea but identified an old bed that led to the Caspian. Writing in the fifteenth century, following the destruction of dams and irrigation works on the Oxus that diverted the river's flow toward the Caspian Sea, the Timurid geographer ...

- ↑ Sala, Renato (28 February 2019). "Quantitative Evaluation of the Impact on Aral Sea Levels by Anthropogenic Water Withdrawal and Syr Darya Course Diversion During the Medieval Period (1.0–0.8 ka BP)". In Yang, Lian Emlyn; Bork, Hans-Rudolf; Fang, Xuiqi; Mishke, Steffen (eds.). Socio-Environmental Dynamics along the Historical Silk Road. Springer, Cham. p. 95-121. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-00728-7_5. ISBN 978-3-030-00727-0. S2CID 134377831.

- ↑ Chan, Leo (2003). One Into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Rodopi. p. 285. ISBN 9789042008151. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Lockard, Craig (2020). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 260. ISBN 9780357365472. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "The Development of the Oil and Gas Industry in Azerbaijan Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine". SOCAR[full citation needed]

- ↑ "Back to the Future: Britain, Baku Oil and the Cycle of History Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine". SOCAR[full citation needed]

- ↑ "Caspian Sea Map, Caspian Sea Location Facts History, Major Bodies of Water". World Atlas. 29 September 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Fedor I. Soimonov". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Kalyuzhnova, Y. (2008). Economics of the Caspian Oil and Gas Wealth: Companies, Governments, Policies. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-22755-2. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "Commission of the Russian Federation for UNESCO". www.unesco.ru. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "The Astana Times". astanatimes.com. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "British Investors Consider Plan to Create Caspian Digital Hub in Aktau". The Astana Times. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Geld, Bernard (9 April 2002). "Caspian Oil and Gas: Production and Prospects" (PDF). wvvw.iwar.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "LUKOIL starts up V. Filanovsky in the Caspian Sea". 31 October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "Volume of oil tanker transportation in Caspian Sea to increase". AzerNews.az. 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "Caspian Sea-Black Sea Transport". Georgia Today on the Web. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "The Great Gas Game Archived 2007-06-08 at the Wayback Machine", Christian Science Monitor (2001-10-25)

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Sergei Blagov, "Russia Tries to Scuttle Proposed Trans-Caspian Pipeline Archived 2007-06-10 at the Wayback Machine", Eurasianet (2006-03-27)

- ↑ "Russia Seeking To Keep Kazakhstan Happy Archived 2008-05-12 at the Wayback Machine", Eurasianet (2007-12-10)

- ↑ Tim Webb (15 December 2010). "WikiLeaks cables: BP suffered blowout on Azerbaijan gas platform". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Walt, Vivienne (18 December 2010). "WikiLeaks Reveals BP's 'Other' Offshore Drilling Disaster". Time. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Characteristics of Caspian Sea". Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ↑ Khoshbakht B. Yusifzade. "8.3 The Status of the Caspian Sea – Dividing Natural Resources Between Five Countries". Azer.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ "The great Caspian arms race", Foreign Policy, June 2012, archived from the original on 9 October 2014, retrieved 6 March 2017

- ↑ "Russia Gets Way in Caspian Meet". Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Nicola Contessi (April 2015), "Traditional Security in Eurasia: The Caspian caught between Militarisation and Diplomacy", The RUSI Journal, vol. 160, no. 2, pp. 50–57, doi:10.1080/03071847.2015.1031525, S2CID 152614480

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Five Leaders Attend Caspian Summit". RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "Five States Sign Convention On Caspian Legal Status". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ "Caspian Sea states to host sea-related investment forum every two years". astanatimes.com. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ↑ "Are the Littoral States Close to Signing an Agreement on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea?". Jamestown. The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "The working group agreed on the provisional agenda of the Caspian summit and the draft of final document". caspianbarrel.org. 30 May 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Is the Caspian a sea or a lake?". The Economist. 16 August 2018. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ "Drainage basin of the Caspian Sea" (PDF). UNECE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Caspian Canal Could Boost Kazakh Trade" Archived 2009-01-19 at the Wayback Machine Business Week (2007-07-09)

External links

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 452–455.

- Names of the Caspian Sea

- Caspian Sea Region

- Dating Caspian sea level changes

- Caspian Sea

- Ancient lakes

- Azerbaijan–Iran border

- Azerbaijan–Russia border

- Border tripoints

- Endorheic lakes of Europe

- Endorheic lakes of Asia

- Eutrophication

- Geography of Central Asia

- Geography of Europe

- Geography of Southern Russia

- Geography of West Asia

- International disputes

- International lakes of Asia

- International lakes of Europe

- Iran–Soviet Union border

- Iran–Turkmenistan border

- Kazakhstan–Russia border

- Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan border

- Lakes of Astrakhan Oblast

- Lakes of Azerbaijan

- Lakes of Dagestan

- Lakes of Iran

- Lakes of Kalmykia

- Lakes of Kazakhstan

- Lakes of Russia

- Lakes of Turkmenistan

- Landforms of Central Asia

- Landforms of West Asia

- Lowest points of countries

- Saline lakes of Asia

- Saline lakes of Europe