Kingdom of the Lombards

Kingdom of the Lombards | |

|---|---|

| 568–774 | |

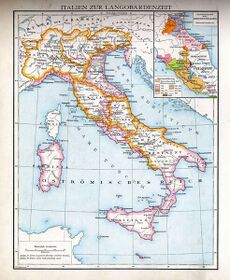

| The Lombard Kingdom 751, under King Aistulf. The Lombard Kingdom 751, under King Aistulf. | |

| Capital | Pavia |

| Official languages | Medieval Latin |

| Common languages | Vulgar Latin Lombardic |

| Religion | Christianity

|

| Government | Feudal elective monarchy |

| King | |

• 565–572 | Alboin (first) |

• 756–774 | Desiderius (last) |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

• Lombard migration | 568 |

| 774 | |

| Currency | Tremissis |

| History of Italy |

|---|

| Old map of Italian peninsula |

| flag Italy portal |

The Kingdom of the Lombards,[1] also known as the Lombard Kingdom and later as the Kingdom of all Italy (Latin: Regnum totius Italiae), was an early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part of the 6th century. The king was traditionally elected by the very highest-ranking aristocrats, the dukes, as several attempts to establish a hereditary dynasty failed. The kingdom was subdivided into a varying number of duchies, ruled by semi-autonomous dukes, which were in turn subdivided into gastaldates at the municipal level. The capital of the kingdom and the center of its political life was Pavia in the modern northern Italian region of Lombardy. The Lombard invasion of Italy was opposed by the Byzantine Empire, which had control of the peninsula at the time of the invasion. For most of the kingdom's history, the Byzantine-ruled Exarchate of Ravenna and Duchy of Rome separated the northern Lombard duchies, collectively known as Langobardia Maior, from the two large southern duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, which constituted Langobardia Minor. Because of this division, the southern duchies were considerably more autonomous than the smaller northern duchies. Over time, the Lombards gradually adopted Roman titles, names, and traditions. By the time Paul the Deacon was writing in the late 8th century, the Lombardic language, dress and hairstyles had all disappeared.[2] Initially the Lombards were Arian Christians or pagans, which put them at odds with the Roman population as well as the Byzantine Empire and the Pope. However, by the end of the 7th century, their conversion to Catholicism was all but complete. Nevertheless, their conflict with the Pope continued and was responsible for their gradual loss of power to the Franks, who conquered the kingdom in 774. Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, adopted the title "King of the Lombards", although he never managed to gain control of Benevento, the southernmost Lombard duchy. The Kingdom of the Lombards at the time of its demise was the last minor Germanic kingdom in Europe. Some regions were never under Lombard domination, including Latium, Sardinia, Sicily, Calabria, Naples, Venice and southern Apulia. A reduced Regnum Italiae, a heritage of the Lombards, continued to exist for centuries as one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, roughly corresponding to the territory of the former Langobardia Maior. The so-called Iron Crown of Lombardy, one of the oldest surviving royal insignias of Christendom, may have originated in Lombard Italy as early as the 7th century and continued to be used to crown kings of Italy until Napoleon Bonaparte in the early 19th century.

Administration

The Lombard Kingdom (Neustria, Austria and Tuscia) and the Lombard Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento

The earliest Lombard law code, the Edictum Rothari, may allude to the use of seal rings, but it is not until the reign of Ratchis that they became an integral part of royal administration, when the king required their use on passports. The only evidence for their use at the ducal level comes from the Duchy of Benevento, where two private charters contain requests for the duke to confirm them with his seal. The existence of seal rings "testifies to the tenacity of Roman traditions of government".[3]

History

6th century

Founding of the kingdom

In the 6th century Byzantine Emperor Justinian attempted to reassert imperial authority in the territories of the Western Roman Empire. In the resulting Gothic War (535–554) waged against the Ostrogothic Kingdom, Byzantine hopes of an early and easy triumph evolved into a long war of attrition that resulted in mass dislocation of population and destruction of property. Problems were further exacerbated by volcanic winter (536), causing widespread famine (538–542) and a devastating plague pandemic (541–542). Although the Byzantine Empire eventually prevailed, the triumph proved to be a pyrrhic victory, as all these factors caused the population of the Italian Peninsula to crash, leaving the conquered territories severely underpopulated and impoverished. Although an invasion attempt by the Franks, then allies of the Ostrogoths, late in the war was successfully repelled, a large migration by the Lombards, a Germanic people that had been previously allied with the Byzantine Empire, ensued. In the spring of 568 the Lombards, led by King Alboin, moved from Pannonia and quickly overwhelmed the small Byzantine army left by Narses to guard Italy. The Lombard arrival broke the political unity of the Italian Peninsula for the first time since the Roman conquest (between the 3rd and 2nd century BC). The peninsula was now torn between territories ruled by the Lombards and the Byzantines, with boundaries that changed over time. The newly arrived Lombards were divided into two main areas in Italy: the Langobardia Maior, which comprised northern Italy gravitating around the capital of the Lombard kingdom, Ticinum (the modern-day city of Pavia in the Italian region of Lombardy); and Langobardia Minor, which included the Lombard duchies of Spoleto and Benevento in southern Italy. The territories which remained under Byzantine control were called "Romania" (today's Italian region of Romagna) in northeastern Italy and had its stronghold in the Exarchate of Ravenna.

Arriving in Italy, King Alboin gave control of the Eastern Alps to one of his most trusted lieutenants, Gisulf, who became the first Duke of Friuli in 568. The duchy, established in the Roman town of Forum Iulii (modern-day Cividale del Friuli), constantly fought with the Slavic population across the Gorizia border.[4] Justified by its exceptional military needs, the Duchy of Friuli thus had greater autonomy compared to other duchies of Langobardia Maior until the reign of Liutprand (712–744). Over time, other Lombard duchies were created in major cities of the kingdom. This was dictated primarily by immediate military needs as dukes were primarily military commanders, tasked to secure control of territory and guard it against possible counter-attacks. However, the resulting collection of duchies also contributed to political fragmentation and sowed the seeds of the structural weakness of the Lombard royal power.[5] In 572, after the capitulation of Pavia and its elevation to the royal capital, King Alboin was assassinated in a conspiracy in Verona plotted by his wife Rosamund and her lover, the noble Helmichis, in league with some Gepid and Lombard warriors. Helmichis and Rosamund's attempt to usurp power in place of the assassinated Alboin, however, gained little support from Lombard duchies, and they were forced to flee together to the Byzantine territory before getting married in Ravenna.

Cleph and the Rule of the Dukes

Later in 572, the thirty-five dukes assembled in Pavia to hail king Cleph. The new monarch extended the boundaries of the kingdom, completing the conquest of Tuscia and laying siege to Ravenna. Cleph tried to pursue the policy of Alboin consistently, which aimed to break the legal-administrative institutions firmly established during Ostrogoth and Byzantine rule. He achieved this by eliminating much of the Latin aristocracy, through occupying their lands and acquiring their assets. However, he too, fell victim to regicide in 574, slain by a man in his entourage who perhaps colluded with the Byzantines. Following Cleph's assassination another king was not appointed, and for a decade[6] dukes ruled as absolute monarchs in their duchies. At this stage, the occupation of the dukes was simply the heads of the various fara (families) of the Lombard people. Not yet firmly associated with the cities, they simply acted independently, also because they were under pressure from the warriors nominally under their authority to allow them to loot. This unstable situation, which persisted over time, led to the final collapse of the Roman-Italic political-administrative structure, which was almost maintained up to the invasion, so that the same Roman-Italic aristocracy had retained responsibility for civil administration (as exemplified by the likes of Cassiodorus). In Italy, the Lombards then imposed themselves at first as the dominant caste in place of the former lineages, who were subsequently extinguished or exiled. The products of the land were allocated to his Roman subjects that worked it, giving to the Lombards a third (tertia) of crops. The proceeds were not given to individuals but to the family, which administered them in the halls (a term still used in the Italian toponymy). The economic system of late antiquity, which focused on large estates worked by peasants in semi-servile condition, was not revolutionized, but modified only to benefit the new rulers.[7]

Final settlement: Autari, Agilulf and Theudelinda

After ten years of interregnum, the need for a strong centralised monarchy was clear even to the most independent of the dukes; Franks and Byzantines pressed and the Lombards could no longer afford so fluid a power structure, useful only to make forays in search of plunder. In 584 the dukes agreed to crown King Cleph's son, Autari, and delivered to the new monarch half of their property (and then probably getting even with a new crackdown against the surviving Roman property land).[8] Autari was then able to reorganise the Lombards and stabilise their settlement in Italy. He assumed, like the Ostrogoth Kings, the title of Flavio, with which he intended to proclaim himself also protector of all Romans in Lombard territory: it was a clear call, with anti-Byzantine overtones, to the heritage of the Western Roman Empire.[9] From the military point of view, Autari defeated both the Byzantines and Franks and broke the coalition, thereby fulfilling the mandate with which the dukes had entrusted him at the time of his election. In 585 he drove the Franks into modern Piedmont and led the Byzantines to ask, for the first time since the Lombards had entered Italy, for a truce. At the end, he occupied the last Byzantine stronghold in northern Italy: Isola Comacina in Lake Como. To ensure a stable peace with the Franks, Autari attempted to marry a Frankish princess, but the project failed. Then the king, in a move that would influence the fate of the kingdom for more than a century, turned to the traditional enemies of the Franks, the Bavarii, to marry a princess, Theodelinda, from the Lethings dynasty. This allowed the monarchy to trace a line of descent from Wacho, king of the Lombards between 510 and 540, a figure surrounded by an aura of legend, and a member of a respected royal line. The alliance with the Bavarii led to a rapprochement between Franks and Byzantines, but Autari managed (in 588 and again, despite some severe early setbacks, in the 590s) to repel the resulting Frankish attacks. The period of Autari marked, according to Paul the Deacon, the attainment of the first internal stability in the Lombard kingdom:

Erat hoc mirabile in regno Langobardorum: nulla erat violentia, nullae struebantur insidiae; nemo aliquem iniuste angariabat, nemo spoliabat; non erant furta, non latrocinia; unusquisque quo libebat securus sine timore

There was a miracle in the kingdom of the Lombards: there was no violence, no insidious plot; no others unjustly oppressed, no depredations; there were no thefts, there were no robberies, where everyone went where they wanted, safely and without fear

— Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, III, 16

Autari died in 590, probably due to poisoning in a palace plot and, according to the legend recorded by Paul the Deacon,[10] the succession to the throne was decided in a novel fashion. It was the young widow Theodelinda who chose the heir to the throne and her new husband: the Duke of Turin, Agilulf. The following year (591) Agilulf received the official investiture from the Assembly of the Lombards, held in Milan. The influence of the queen over Agilulf's policies was remarkable and major decisions are attributed to both.[11]

After a rebellion among some dukes in 594 was preempted, Agilulf and Theodelinda developed a policy of strengthening their hold on Italian territory, while securing their borders through peace treaties with France and the Avars. The truce with the Byzantines was systematically violated and the decade up to 603 was marked by a notable recovery of the Lombard advance. In northern Italy Agilulf occupied, among other cities, Parma, Piacenza, Padova, Monselice, Este, Cremona and Mantua, but also to the south the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, extending the Lombards' domains. Istria was attacked and invaded by the Lombards on several occasions, although the degree of their occupation of the peninsula and its subordination to the Lombard kings is unclear. Even when Istria was part of the Exarchate of Ravenna, a Lombard, Gulfaris, rose to power in the region, styling himself as dux Istriae.[12] The strengthening of royal powers, started by Autari and continued by Agilulf, also marked the transition to a new concept based on stable territorial division of the kingdom into duchies. Each duchy was led by a duke, not just the head of a fara but also a royal official, the depository of public powers. The locations of the duchies were established in strategically important centers, thus furthering the development of many urban centers placed along the main communication routes of the time (Cividale del Friuli: Treviso, Trento, Turin, Verona, Bergamo, Brescia, Ivrea, Lucca). In the management of public power dukes were joined by minor officials, these the sculdahis and the gastald. The new organisation of power, less linked to race and clan relations and more to land management, marked a milestone in the consolidation of the Lombard kingdom in Italy, which gradually lost the character of a pure military occupation and approached a more proper state model.[11] The inclusion of the losers (the Romans) was an inevitable step, and Agilulf made some symbolic choices aimed at the same time at strengthening its power and gaining credit with people of Latin descent. The ceremony of ascension to the throne of his son Adaloald in 604, followed a Byzantine rite. He chose not to continue to use Pavia as the capital, but the ancient Roman city of Milan with Monza as a summer residence. He identified himself, in a votive crown, Gratia Dei rex totius Italiae, "By the grace of God king of all Italy", and not just Langobardorum rex, "King of the Lombards".[13] Moves in this direction also included strong pressure, particularly from Theodelinda, to convert the Lombards, who until then were still largely pagan or Arians, to Catholicism. The rulers also endeavored to heal the Three Chapter schism (where the Patriarch of Aquileia had broken communion with Rome), maintained a direct relationship with Gregory the Great (preserved in correspondence between him and Theodelinda) and promote the establishment of monasteries, like the one founded by Saint Columbanus in Bobbio. Even art enjoyed, under Agilulf and Theodelinda, a flourishing season. In architecture Theodelinda founded the Basilica of St. John (also known as the Duomo of Monza) and the Royal Palace of Monza, while some masterpieces in gold were created such as the Agilulf Cross, the Hen with seven chicks, the Theodelinda Gospels and the famous Iron Crown (all resident in the Duomo of Monza treasury).

7th century

Revival of the Arians: Arioald, Rothari

After the death of Agilulf in 616, the throne passed to his son Adaloald, a minor. The regency (which continued even after the king passed into majority)[14] was exercised by the Queen Mother, Theodelinda, who gave command of the military to Duke Sundarit. Theodelinda continued Agilulf's pro-Catholic policy and maintained the peace with the Byzantines, which generated ever-stronger opposition from the warriors and Arians among the Lombards. A civil war broke out in 624, led by Arioald, Duke of Turin and Adaloald's brother-in-law (through his marriage to Adaloald's sister Gundeperga). Adaloald was deposed in 625 and Arioald became king. This coup d'état against the Bavarian dynasty of Adaloald and Theodelinda intensified the rivalry between the Arian and Catholic factions. The conflict had political overtones, as the Arians also opposed peace with Byzantium and the Papacy and integration with the Romans, opting instead for a more aggressive and expansionist policy.[15] Arioald (r. 626–636), who brought the capital back to Pavia, was troubled by these conflicts, as well as external threats; the King was able to withstand an attack of the Avars in Friuli, but could not limit the growing influence of the Franks in the kingdom. At his death, the legend says that, using the same procedure as that followed by his mother Theodelinda, Queen Gundeperga had the privilege to choose her new husband and king.[16] The choice fell on Rothari, the duke of Brescia and an Arian. Rothari reigned from 636 to 652 and led numerous military campaigns, which brought almost all of northern Italy under the rule of the Lombard kingdom. He conquered Liguria (643), including the capital Genoa, Luni, and Oderzo; however, not even a total victory over the Byzantine Exarch of Ravenna, defeated and killed along with his eight thousand men at the River Panaro, succeeded in forcing the Exarchate to submit to the Lombards.[17] Internally, Rothari strengthened the central power at the expense of the duchies of Langobardia Maior, while in the south the Duke of Benevento, Arechi I (who in turn was expanding Lombard domains), also recognized the authority of the King of Pavia. The memory of Rothari is linked to his famous edict, promulgated in 643 in Pavia by a gairethinx, an assembly of the army,[18] and written in Latin. The Edict consolidated and codified Germanic rules and customs, but also introduced significant innovations, a sign of the progress of Latin influence on the Lombards. The edict tried to discourage the feud (private revenge) by increasing the weregild (financial compensation) for injuries/murders and also contained drastic restrictions on the use of the death penalty.

Bavarian dynasty

After the short reign of the son of Rothari and his son Rodoald (652-653), the dukes elected Aripert I, Duke of Asti and grandson of Theodolinda, as the new king. The Bavarian dynasty returned to the throne, and the Catholic Aripert duly suppressed Arianism. At Aripert's death in 661, his will divided the kingdom between his two sons, Perctarit and Godepert. This method of succession was known from the Romans and Franks,[19] but was a unique case among the Lombards. Perhaps because of this, a conflict broke out between Perctarit, who was based in Milan, and Godepert, who remained in Pavia. The Duke of Benevento, Grimoald, intervened with a substantial military force to support Godepert, but, as soon as he arrived in Pavia, he killed Godepert and took his place. Perctarit, clearly in danger, fled to the Avars. Grimoald was invested by the Lombard nobles, but still had to deal with the legitimate faction, which tried international alliances to return the throne to Perctarit. Grimoald, however, persuaded the Avars to return the deposed ruler. Perctarit, as soon as he returned to Italy, had to make an act of submission to the usurper before he could escape to the Franks of Neustria, who attacked Grimoald in 663. The new king, hated by Neustria because he was allied with the Franks of Austrasia, repulsed them at Refrancore, near Asti. Grimoald, who in 663 had also defeated an attempt to reconquer Italy by the Byzantine Emperor Constans II, exercised his sovereign powers with a fullness never attained by his predecessors.[20] He entrusted the Duchy of Benevento to his son Romuald, and assured the loyalty of the duchies of Spoleto and Friuli, by appointing their dukes. He favoured the integration of the different components of the kingdom, presenting an image modeled on that of his predecessor Rotari—wise legislator in adding new laws to the Edict, patron (building a church in Pavia dedicated to Saint Ambrose), and valiant warrior.[21] With Grimoald's death in 671, his minor son Garibald assumed the throne, but Perctarit returned from exile and swiftly deposed him. He immediately came to an agreement with Grimoald's other son, Romualdo I of Benevento, who pledged loyalty in exchange for recognition of the autonomy of his duchy. Perctarit developed a policy in line with the tradition of his dynasty and supported the Catholic Church against Arianism and the chapters anathematized in the Three-Chapter Controversy. He sought and achieved peace with the Byzantines, who acknowledged Lombard sovereignty over most of Italy, and repressed the rebellion of the Duke of Trent, Alahis, although at the cost of hard territorial concessions to Alahis (including the Duchy of Brescia). Alahis rebelled again later, joining with the political opponents of the pro-Catholic Bavarian policy at Perctarit's death in 688. His son and successor Cunipert was initially defeated and forced to take refuge on the Isola Comacina - only in 689 did he manage to quash the rebellion, defeating and killing Alahis in the Battle of Coronate at the Adda.[22]

The crisis resulted from the divergence between the two regions of Langobardia Maior: Neustria, to the west, was loyal to the Bavarian rulers, pro-Catholic and supporters of the policy of reconciliation with Rome and Byzantium; on the other hand, Austria, to the east, identified with the traditional Lombard adherence to paganism and Arianism, and favored a more warlike policy. The dukes of Austria challenged the increasing "latinization" of customs, court practices, law and religion, which they believed accelerated the disintegration and loss of the Germanic identity of the Lombard people.[22] The victory allowed Cuniperto, already long associated with the throne by his father, to continue the work of pacifying the kingdom, always with a pro-Catholic accent. A synod convened in Pavia in 698 sanctioned the reintegration of the three anathematized chapters into Catholicism.

8th century

Dynastic crisis

Cunipert's death in 700 marked the opening of a dynastic crisis. The succession of Cunipert's minor son, Liutpert, was immediately challenged by the Duke of Turin, Raginpert, the most prominent of the Bavarian dynasty. Raginpert defeated the supporters of Liutpert (viz., his tutor Ansprand, Duke of Asti, and the Duke of Bergamo, Rotarit) in Novara, and, at the beginning of 701, took the throne. However, he died after just eight months, leaving the throne to his son Aripert II. Ansprand and Rotarit reacted immediately and imprisoned Aripert, returning the throne to Liutpert. Aripert, in turn, managed to escape and confront his rival's supporters. In 702, he defeated them in Pavia, imprisoned Liutpert and occupied the throne. Shortly after, he finally defeated the opposition: he killed Rotarit, suppressed his duchy, and drowned Liutpert. Only Ansprand managed to escape, taking refuge in Bavaria. Subsequently, Aripert crushed a new rebellion, that of the Duke of Friuli, Corvulus, and adopted a strongly pro-Catholic policy. In 712, Ansprand returned to Italy with an army raised in Bavaria, and clashed with Aripert; the battle was uncertain, but the king behaved cowardly and was abandoned by his supporters.[23] He died while trying to escape to the realm of the Franks, and drowned in the Ticino, dragged to the bottom by the weight of the gold that he brought with him.[23] With him ended the Bavarian dynasty's role in the Lombard kingdom.

Liutprand: the apogee of the reign

Ansprand died after only three months of his reign, leaving the throne to his son Liutprand. His reign, the longest of all Lombard monarchs, was characterized by the almost religious admiration that was accorded to the king by his people, who recognized in him boldness, courage and political vision.[24] Thanks to these qualities Liutprand survived two attempts on his life (one organized by one of his relatives, Rotari), and he displayed no inferior qualities in the conduct of the many wars of his long reign. These values are typical of Liutprand: Germanic descent, king of a nation now overwhelmingly Catholic, joined by those of a piissimus rex ("loving king") (despite having tried several times to take control of Rome). On two occasions, in Sardinia and in the region of Arles (where he had been called by his ally Charles Martel) he successfully fought Saracen pirates, enhancing his reputation as a Christian king. His alliance with the Franks, crowned by a symbolic adoption of the young Pepin the Short, and with the Avars, on the eastern borders, allowed him to keep his hand relatively free in the Italian theater, but he soon clashed with the Byzantines and with the Papacy. A first attempt to take advantage of an Arab offensive against Constantinople in 717 achieved few results. Closer relations with the papacy therefore had to wait for the outbreak of tensions caused by the worsening of the Byzantine tax, and the expedition in 724 conducted by the Exarch of Ravenna against Pope Gregory II. Later on he exploited the disputes between the pope and Constantinople over iconoclasm (after the decree of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian of 726) to take possession of many cities of the Exarchate and of the Pentapolis, posing as the protector of Catholics. In order not to antagonize the Pope, he gave up the occupation of the village of Sutri; however, Liutprand gave the city not to the emperor, but to "the apostles Peter and Paul", as Paul the Deacon related in his Historia Langobardorum.[25] This donation, known as the Donation of Sutri, provided the legal basis for attributing a temporal power to the papacy, which finally produced the Papal States. In the following years, Liutprand entered into an alliance with the Exarch against the pope, without giving up the old one with the Pope against the Exarch; he crowned this classic double play with an offensive that led to placing the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento under his authority, eventually arriving to negotiate a peace between the pope and Exarch beneficial to the Lombards. No Lombard king had ever obtained similar results in wars with other powers in Italy. In 732 his nephew Hildeprand, who succeeded him on the throne, briefly took possession of Ravenna, but he was driven away by the Venetians, who had allied with the new pope, Gregory III. Liutprand was the last of the Lombard kings to rule over a unified kingdom; later kings would face substantial internal opposition, which eventually contributed to the kingdom's downfall. The strength of his power was based not only on personal charisma, but also on the reorganization of the kingdom which he had undertaken since the beginning of his reign. He strengthened the chancellery of the royal palace of Pavia and defined in an organic way the territorial competencies (legal and administrative) of sculdasci, gastalds and dukes. He was also very active in the legislative field: the twelve volumes of laws enacted by him introduced legal reforms inspired by Roman law, improved the efficiency of the courts, changed the wergild and, above all, protected the weaker sectors of society, including minors, women, debtors, and slaves.[26][27]

The socio-economic structure of the kingdom had been progressively changing since the 7th century. Population growth led to fragmentation of funds, which increased the number of Lombards who fell below the poverty line, as evidenced by the laws aimed at alleviating their difficulties. By contrast, some Romans began to ascend the social ladder, becoming rich through commerce, crafts, the professions or the acquisition of lands that the Lombards had not been able to manage profitably. Liutprand also intervened in this process by reforming the administrative structure of the kingdom and freeing the poorest Lombards from military obligations.[28]

Last kings

Hildeprand's reign lasted only a few months, before he was overthrown by Duke Ratchis. The details of the episode are not clear, since the crucial testimony of Paul the Deacon ended with a eulogy on the death of Liutprand. Hildeprand had been anointed king in 737, during a serious illness suffered by Liutprand (who did not like the choice of king at all: "Non aequo animo accepit" wrote Paul the Deacon,[29] although, once recovered, he accepted the choice). The new king, then, at least initially enjoyed the support of most of the aristocracy, if not that of the great monarch. Ratchis, the Duke of Friuli, came from a family with a long tradition of rebellion against the monarchy and rivalry with the royal family, but on the other hand, he owed his life and the ducal title to Liutprand, who had forgiven him after discovering a conspiracy headed by his father, Pemmo of Friuli. Ratchis was a weak ruler: on one side he had to concede greater freedom of action to the other dukes, on the other extreme he had to take care not to exacerbate the Franks and, above all, the mayor of the palace and de facto king Pepin the Short, the adopted son of the king whose nephew he had dethroned. Not being able to trust the traditional structures of support for the Lombard monarchy, he sought support among the gasindii, the gentry bound to the king by treaties of protection,[30] and especially among the Romans, the non-Lombard subjects. The adoption of ancient customs, along with public pro-Latin attitudes—he married a Roman woman, Tassia, and with Roman rite, and adopted the title of princeps instead of the traditional rex Langobardorum—increasingly alienated the Lombard base, which forced him to adopt a diametrically opposed policy, with a sudden attack on the cities of the Pentapolis. The pope, however, convinced him to abandon the siege of Perugia. After this failure, the prestige of Ratchis collapsed and the dukes elected as the new king his brother Aistulf, who had already succeeded him as duke in Cividale and now, after a short struggle, forced him to flee to Rome and finally to become a monk in Monte Cassino.

Aistulf

Aistulf expressed the more aggressive stance of the dukes, who refused an active role for the Roman population. For his expansionist policy, however, he had to reorganize the army to include, albeit in the subordinate position of light infantry, all ethnic groups in the kingdom. All free men of the kingdom, both those of Roman and Lombard origin, were obliged to serve in the military. The military standards promulgated by Aistulf mention the merchants several times, a sign of how that class had now become relevant.[31]

Initially, Aistulf achieved some notable successes, culminating in the conquest of Ravenna (751). Here the king, residing in the Palace of the Exarch, and coining money in Byzantine style, presented his program: to collect under Lombard power all the Romans until then subject to the emperor, without necessarily merging them with the Lombards. The Exarchate was not homologous to other Lombard possessions in Italy (that is it was not converted into a duchy), but retained its specificity as sedes imperii; in this way Aistulf proclaimed himself heir in the eyes of Italian Romans of both the Byzantine Emperor and the Exarch, the Emperor's representative.[32] His campaigns led the Lombards to a near-complete domination of Italy, with the occupation also of Istria, Ferrara, Comacchio, and all territories south of Ravenna up to Perugia, from 750 to 751. With the occupation of the stronghold of Ceccano, he was putting further pressure on the territories controlled by Pope Stephen II, while in Langobardia Minor he was able to impose his power on Spoleto and, indirectly, on Benevento. Just when it seemed Aistulf was able to defeat all opposition on Italian soil, Pepin the Short, the old enemy of the usurpers of Liutprand's family, finally managed to overthrow the Merovingian dynasty in Gaul, deposing Childeric III and becoming king de jure as well as de facto. The support Pepin enjoyed from the papacy was decisive, although negotiations were also underway between Aistulf and the pope (which soon failed), and an attempt was made to weaken Pepin by turning his brother Carloman against him. Because of the threat this move represented for the new king of the Franks, an agreement between Pepin and Stephen II settled, in exchange for the formal royal anointing, the descent of the Franks in Italy. In 754, the Lombard army, deployed in defence of the Locks in Val di Susa, was defeated by the Franks. Aistulf, perched in Pavia, had to accept a treaty that required the delivery of hostages and territorial concessions, but two years later resumed the war against the pope, who in turn called on the Franks. Defeated again, Aistulf had to accept much harsher conditions: Ravenna was returned not to the Byzantines, but to the pope, increasing the core area of the Patrimony of St. Peter; Aistulf had to accept a sort of Frankish protectorate, the loss of territorial continuity of his domains, and payment of substantial compensation. The duchies of Spoleto and Benevento were quick to ally themselves with the victors. Aistulf died in 756, shortly after this severe humiliation. Aistulf's brother Ratchis left the monastery and attempted, initially with some success, to return to the throne. He opposed Desiderius, who was put in charge of the Duchy of Tuscia by Aistulf and based in Lucca; he did not belong to the dynasty of Friuli, frowned upon by the pope and the Franks, and managed to get their support. The Lombards surrendered to him to avoid another Frankish invasion, and Rachis was persuaded by the Pope to return to Monte Cassino. Desiderius, with a clever and discreet policy, gradually reasserted Lombard control over the territory by gaining favor with the Romans again, creating a network of monasteries ruled by Lombard aristocrats (his daughter Anselperga was named abbess of San Salvatore in Brescia), dealing with Pope Stephen II's successor, Pope Paul I, and recognizing the nominal domain on many areas truly in his power, such as reclaimed southern duchies. He also implemented a casual marriage policy, marrying his daughter Liutperga to the Duke of Bavaria, Tassilo (763), historical adversary of the Franks and, at the death of Pepin the Short, by marrying the other daughter Desiderata (who was immortalised in the tragedy Adelchi by Alessandro Manzoni as Ermengarde) to the future Charlemagne, offering him a useful support in the fight against his brother Carloman. Despite the changing fortunes of central political power, the 8th century represented the apogee of the reign, also a period of economic prosperity. The ancient society of warriors and subjects had been transformed into a vivid articulation of classes with landowners, artisans, farmers, merchants, lawyers; the era saw great development, including abbeys, notably Benedictine, and expanded monetary economics, resulting in the creation of a banking class.[33] After an initial period during which Lombard coinage only imitated Byzantine coins, the kings of Pavia developed an independent gold and silver coinage. The Duchy of Benevento, the most independent of the duchies, also had its own independent currency.

Fall of the kingdom

In 771, Desiderius managed to convince the new pope, Stephen III, to accept his protection. The death of Carloman left Charlemagne, now firmly on the throne after repudiating the daughter of Desiderius, freehanded. The following year a new pope, Adrian I, of the opposite party of Desiderius, reversed the delicate game of alliances, demanding the surrender of the area never ceded by Desiderius and thus causing him to resume the war against the cities of Romagna.[34] Charlemagne, though he had just begun his campaign against the Saxons, came to the aid of the pope. He feared the capture of Rome by the Lombards and the consequent loss of prestige that would follow. Between 773 and 774 he invaded Italy. Once again the defence of the Locks was ineffective, the fault of the divisions among the Lombards.[34] Charlemagne, having prevailed against a tough resistance, captured the capital of the kingdom, Pavia. Adalgis, the son of Desiderius, found refuge with the Byzantines. Desiderius and his wife were deported to Gaul. Charles then called himself Gratia Dei rex Francorum et Langobardorum ("By the grace of God king of the Franks and the Lombards"), realizing a personal union of the two kingdoms. He maintained the Leges Langobardorum, but reorganized the kingdom on the Frankish model, with counts in place of dukes.

Thus ended Lombard Italy, and nobody can say whether this was, for our country, a fortune or a misfortune. Alboin and his successors were awkward masters, more awkward than Theodoric, so long as they had been barbarians camped on a conquered territory. But now they were assimilating with Italy and could turn it into a Nation, as the Franks were doing in France. But in France there wasn't the Pope. In Italy, there was.

— Indro Montanelli - Roberto Gervaso, L'Italia dei secoli bui

After the Frankish conquest of Langobardia Maior, only the Southern Lombard Kingdom was called Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), as attested in the Norse Runestones.[35]

List of monarchs

Historiographical views

The age of the Lombard kingdom was, especially in Italy, devalued as a long reign of barbarism[36] in the midst of the "Dark Ages". A period of confusion and dispersion, marked by the abandoned ruins of a glorious past and still in search of new identity; see, for example, the verses of Manzoni's Adelchi:

From the mossy atria, from the crumbling Fora,

from the woods, from the flaming strident forges,

from the furrows wet with slave sweat,

a dispersed mob suddenly awoke.

Dagli atri muscosi, dai Fori cadenti,

dai boschi, dall'arse fucine stridenti,

dai solchi bagnati di servo sudor,

un volgo disperso repente si desta.— Alessandro Manzoni, Adelchi, Choir Third Act.

Sergio Rovagnati defines the continuing negative prejudice against the Lombards as "a sort of damnatio memoriae", common to that given often to all the protagonists of the barbarian invasions.[37] The most recent historiographical guidelines, however, have largely reassessed the Lombard era of the history of Italy. The German historian Jörg Jarnut pointed out[38] all the elements that constitute the historical importance of the Lombard kingdom. The historical bipartition of Italy that has, for centuries, directed the North towards Central-Western Europe and the South, instead, to the Mediterranean area dates back to the separation between Langobardia Major and Langobardia Minor, while Lombard law influenced the Italian legal system for a long time, and was not completely abandoned even after the rediscovery of Roman law in the 11th and 12th centuries. Regarding the role played by the Lombards within the emerging Europe, Jarnut[39] shows that, after the decline of the kingdom of the Visigoths and during the period of weakness of the kingdom of the Franks in the Merovingian era, Pavia was about to take a guiding role for the West after determining, by tearing a large part of Italy from the dominance of the Basileus, the final boundary line between the Latin-Germanic West and the Greek-Byzantine East. The rise of the Lombards in Europe was halted, however, by the growing power of the Frankish kingdom under Charlemagne, who inflicted decisive defeats on the last kings of the Lombards. The military defeat, however, did not correspond to a disappearance of the Lombard culture: Claudio Azzara states that "the same Carolingian Italy is configured, in fact, as a Lombard Italy, in the constituent elements of society and culture".[40]

In the arts

Literature

The persistent injury historiography on the "Dark Ages" has long cast shadows on the Lombard kingdom, averting the interest of writers from that period. Few literary works have been set in Italy between the 6th and 8th centuries; between them, relevant exceptions are those of Giulio Cesare Croce and Alessandro Manzoni. More recently the Friulian writer Marco Salvador has devoted a fiction trilogy to the Lombard kingdom.

Berthold

The figure of Bertoldo/Berthold, a humble and clever farmer from Retorbido, who lived during the reign of Alboin (568-572), inspired many oral traditions throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period. In them the 17th-century scholar Giulio Cesare Croce found inspiration in his Le sottilissime astutie di Bertoldo ("the smart craftiness of Berthold") (1606), to which, in 1608, he added Le piacevoli et ridicolose simplicità di Bertoldino ("The pleasant and ridiculous simplicity of Little Berthold"), about Berthold's son. In 1620, the abbot Adriano Banchieri, poet and composer, produced a further follow-up: Novella di Cacasenno, figliuolo del semplice Bertoldino ("News of Cacasenno, son of simple Little Berthold"). Since then, the three works are usually published in one volume under the title of Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno.

Adelchi

Set during the extreme end of the Lombard kingdom, the Manzonian tragedy Adelchi tells the story of the last king of the Lombards, Desiderius and his children Ermengarde (whose real name was Desiderata) and Adalgis: the first the divorced wife of Charlemagne, and the second the last defender of the Lombard kingdom against the Frankish invasion. Manzoni used the Lombard kingdom as the scene, adjusting its interpretation of the characters (the real centers of the work) and portrayed the Lombards as having a role in paving the way to Italian national unity and independence, while reproducing a then-dominant image of a barbaric period after the classical splendor.

Cinema

Three films were inspired by stories of Croce and Banchieri and set in the initial period of the Lombard kingdom (very freely played):

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1936), directed by Giorgio Simonelli;

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1954), directed by Mario Amendola and Ruggero Maccari;

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1984), directed by Mario Monicelli.

By far the most famous is the last of the three films, which boasted a cast composed of, among others, Ugo Tognazzi (Berthold), Maurizio Nichetti (Little Berthold), Alberto Sordi (fra Cipolla) and Lello Arena (king Alboin).

See also

References

- ↑ (Latin: Regnum Langobardorum; Italian: Regno dei Longobardi; Lombard: Regn di Lombard)

- ↑ "The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500-c. 700" by Paul Fouracre and Rosamond McKitterick (page 8)

- ↑ N. Everett (2003), Literacy in Lombard Italy, c. 568–744 (Cambridge), 170.

- ↑ cf. Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, IV, 37; VI, 24-26 e 52.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), pp. 48–50.

- ↑ or twelve years, according Origo gentis Langobardorum and Chronicle of Fredegar.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 37.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, III, 16.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, III, 35.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Jarnut (1995), p. 44.

- ↑ Martyn, John R. C (2012). Pope Gregory's Letter-Bearers: A Study of the Men and Women who carried letters for Pope Gregory the Great. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-443-83918-1.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 43.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, IV, 41.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 61.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 56.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, IV, 45.

- ↑ "Lombard terms and Latin glosses from the Codex Eporedianus of the Edictum Rothari". Arca. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ In this regard, it is worth mentioning the partition Pepin the Younger divided his kingdom between his two sons Carloman and Charlemagne.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 59.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, IV, 46.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Franco Cardini e Marina Montesano, Storia medievale, pag. 86.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Paolo Diacono, VI, 35.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 97.

- ↑ Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, VI, 49.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 82.

- ↑ Sergio Rovagnati, I Longobardi, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Paul Deacon, Historia Langobardorum, VI, 55.

- ↑ Leges Langobardorum, Ratchis Leges, 14, 1-3.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 101.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 112.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), p. 102.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Jarnut (1995), p. 125.

- ↑ 2. Runriket - Täby Kyrka Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, an online article at Stockholm County Museum, retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ cf. Azzara (2002), p. 135

- ↑ Rovagnati (2003), p. 1

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Jarnut (1995), pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Azzara (2002), p. 138

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Chronicle of Fredegar, Pseudo-Fredegarii scholastici Chronicarum libri IV cum continuationibus in Monumenta Germaniae Historica SS rer. Mer. II, Hanover 1888

- Gregory of Tours, Gregorii episcopi Turonensis Libri historiarum X (Historia Francorum) in Monumenta Germaniae Historica SS rer. Mer. I 1, Hanover 1951

- Leges Langobardorum (643-866), ed. F. Beyerle, Witzenhausen 1962

- Marius Aventicensis, Chronica a. CCCCLV-DLXXXI. edited Theodor Mommsen in Monumenta Germaniae Historica AA, XI, Berlin 1894

- Origo gentis Langobardorum, ed. G. Waitz in Monumenta Germaniae Historica SS rer. Lang.

- Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum (Storia dei Longobardi, Lorenzo Valla/Mondadori, Milan 1992)

Historiographical literature

- Chris Wickham (1981). Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society, 400–1000. MacMillan Press.

- Azzara, Claudio; Gasparri, Stefano, eds. (2005). Le leggi dei Longobardi: storia, memoria e diritto di un popolo germanico (in italiano) (2 ed.). Roma: Viella. ISBN 88-8334-099-X.

- Azzara, Claudio (2002). L'Italia dei barbari (in italiano). Bologna: Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-08812-1.

- Paolo Delogu. Longobardi e Bizantini in Storia d'Italia, Torino, UTET, 1980. ISBN 88-02-03510-5.

- Bandera, Sandrina (2004). Declino ed eredità dai Longobardi ai Carolingi. Lettura e interpretazione dell'altare di S. Ambrogio (in italiano). Morimondo: Fondazione Abbatia Sancte Marie de Morimundo.

- Bertelli, Carlo; Gian Pietro Broglio (2000). Il futuro dei Longobardi. L'Italia e la costruzione dell'Europa di Carlo Magno (in italiano) (Skira ed.). Milano. ISBN 88-8118-798-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bertolini, Ottorino (1972). Roma e i Longobardi (in italiano). Roma: Istituto di studi romani. BNI 7214344.

- Bognetti, Gian Piero (1957). L'Editto di Rotari come espediente politico di una monarchia barbarica (in italiano). Milano: Giuffre.

- Cardini, Franco; Marina Montesano (2006). Storia medievale (in italiano). Firenze: Le Monnier. ISBN 88-00-20474-0.

- Gasparri, Stefano (1978). I duchi longobardi (in italiano). Roma: La Sapienza.

- Jarnut, Jörg (1995) [1982]. Storia dei Longobardi (in italiano). Translated by Guglielmotti, Paola. Torino: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-13658-5.

- Montanelli, Indro; Roberto Gervaso (1965). L'Italia dei secoli bui (in italiano). Milano: Rizzoli.

- Mor, Carlo Guido (1930). "Contributi alla storia dei rapporti fra Stato e Chiesa al tempo dei Longobardi. La politica ecclesiastica di Autari e di Agigulfo". Rivista di storia del diritto italiano (Estratto).

- Neil, Christie (1997). I Longobardi. Storia e archeologia di un popolo (in italiano). Genova: ECIG. ISBN 88-7545-735-2.

- Possenti, Paolo (2001). Le radici degli italiani. Vol. II: Romania e Longobardia (in italiano). Milano: Effedieffe. ISBN 88-85223-27-3.

- Rovagnati, Sergio (2003). I Longobardi (in italiano). Milano: Xenia. ISBN 88-7273-484-3.

- Tagliaferri, Amelio (1965). I Longobardi nella civiltà e nell'economia italiana del primo Medioevo (in italiano). Milano: Giuffrè. BNI 6513907.

- Tabacco, Giovanni (1974). Storia d'Italia. Vol. I: Dal tramonto dell'Impero fino alle prime formazioni di Stati regionali (in italiano). Torino: Einaudi.

- Tabacco, Giovanni (1999). Egemonie sociali e strutture del potere nel medioevo italiano (in italiano). Torino: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-49460-0.