Languages of the Comoros

| Languages of the Comoros | |

|---|---|

| File:Mayotte is Comorian (10896486873).jpg Political poster in French in Moroni | |

| Official | Comorian, French and Arabic |

| Recognised | Bushi, Malagasy, Maore |

| Vernacular | Français populaire africain |

| Minority | Swahili |

| Foreign | English |

| Signed | American Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | |

The official languages of the Comoros are Comorian, French and Arabic, as recognized under its 2001 constitution.[1] Although each language holds equal recognition under the constitution, language use varies across Comorian society.[2] Unofficial minority languages such as Malagasy and Swahili are also present on the island with limited usage.[3] According to Harriet Joseph Ottenheimer, a professor of anthropology at Kansas State university, the linguistic diversity of the Comoros is the result of its rich history as part of the Indian maritime trade routes and its periods of Malagasy and French colonial rule.[3]

Official languages

Comorian

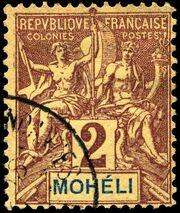

Comorian, or Shikomoro is the most widely spoken language in the country, spoken by 96.9% of the population.[4][5] As a Bantu language, Comorian is closely related to Swahili.[6] Each island has its own dialect of Comorian.[7] The Shingazija dialect is the most widely used variant of Comorian, spoken on Grande Comore (Ngazija) by about 312,000 people. Additionally, the Shimwali dialect is spoken by 29,000 people on Moheli (Mwali) and the Shinzwani dialect is spoken by about 275,000 people on Anjouan (Nzwani).[7][8] Although the dialects have linguistic differences, they all share mutual intelligibility.[7] There is no accepted orthography in the Comorian language.[9] Historically and informally, Comorian was written using a variant of Arabic script, called the Ajami script.[4] Most early academic works written on Comorian are difficult or impossible to obtain because of the lack of written standard.[10] According to John Mugane, professor of African languages at Harvard University, there were extended time gaps ranging from 25 to 30 years throughout the 1900s, which lacked new academic information on the Comorian languages.[11] From the 1600s until the late 1990s, only two dozen publication have included the languages of the Comoros.[7] Many academic publications have only been passing references in other language studies or the accounts of travelers.[7] When Comorian was first identified in the 1880s, there was much debate over whether it was a variant of Swahili or a separate language.[10] But according to Martin Ottenheimer, a professor of anthropology at Kansas State University, grammatical and linguistic differences discovered by French linguists such as Charles Sacleux and Antoine Meillet, have affirmed the distinctiveness of Comorian as a separate language from Swahili.[7] For example, although both languages share similar vocabularies, there is a consistent mutual unintelligibility between Swahili and Comorian.[7] Upon independence from France in 1975, Comorian was sought as an official language, and a Latin-based orthography was demanded by the Comorian government.[9] In particular, both the government and the people of the Comoros sought for a writing system that was distinct from French, whilst resembling its nearby East African nations.[9] Since the 1970s, attempts have been made by both the Comorian government and the University of the Comoros Department of Modern Languages to standardize the Comorian language and integrate it into the education system alongside French and Arabic.[12][9] In 1976, two Latin-based orthographies were proposed by the country's president, Ali Soilihi and the linguist Mohamed Ahmed-Chamang.[10][11] In 1986, a Swahili-based orthography was proposed by Comorian linguist Moinaecha Cheikh.[7] However, the past attempts to introduce a Comorian orthography has failed to gain popularity. Political, historical and ethnic tensions regarding the different dialects of Comorian have been responsible for the failed attempts to provide a written standard for Comorian.[7][2] For example, the orthography proposed by Cheikh was widely unpopular as the writing system was more suited towards the Shingazidja dialect rather than the Shinzwani dialect.[3]

There has been significant debate over which variant of the Comorian language is considered as the national language.[2] According to Martin-Luther University professor Iain Walker, this debate has been largely avoided in Comorian politics, which has contributed to an increasing sociolinguistic disunity between the speakers of each variant.[2]

French

French is the second most spoken language in the Comoros. According to a 2018 report by the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, 216,174 people, or 25.97% of the population, spoke French in the Comoros.[13] The language emerged as a result of French colonisation in the Comoros, lasting from 1841 until independence in 1975.[2] French is considered the language of government and commerce and is acquired through formal, non-Qur’anic education.[4] After independence, the use of the French language was propagated during the administration of the pro-French president, Ahmed Abdallah.[4] The Abdallah administration had reinforced the use of French in education and provided official, French place names in the country.[4] Internationally, the Comoros is recognised as a Francophone nation, and is a full member of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. During the colonial period, French was the main language of instruction across society, including administration, education and trade.[4] Higher education is also dependent on French language ability, as many Comorian students attend universities in France.[14]

Arabic

Although an official language, Arabic is a minority language in the Comoros Islands. Arabic functions as a liturgical language for the country's dominant religion, Islam, adhered to by 95% of the population.[15] Despite being an official language, Arabic is not widely used in the Comoros and it is not reported as a first language (L1) amongst the population.[8] Historically, Arabic was a language of commerce, used for trade in the Comoros for over fifteen hundred years.[4][10] Arabic was first introduced as a result of increased Arabian maritime contact during the slave trade from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century.[4] These influences had persisted with the spread of various Arabic publications such as Al Falaq in neighbouring Tanzania and the Comoros.[16] This led to the emergence of Islam, and the creation of the Koranic School in the 16th century which instructed children in the practices and beliefs of Islam and propagated the use of the Arabic language.[4][6] From the 1970s, the use of Arabic gradually began to separate from religious purposes.[4] The teaching of Arabic as a secular subject and at an advanced level started to gain popularity.[8][4] Arabic languages skills came to be regarded as privilege in Comorian society.[4] But, Arabic language use remains largely assigned to religious purposes. This is primarily due to the lasting importance of the Quranic School in the Comorian education system, existing in Comoros for more than four centuries.[4] The Comoros participates in international delegations tied to promoting Arabic language use.[14] Six Arabo-Islamic colleges and an Institute for Arabic Language were constructed with financial support from the World Islamic League and Kuwait.[4] Similar to French, higher education in the Comoros is tied Arabic language usage, with many Comorian students receiving tertiary education in Arabic-speaking countries.[14] The Comoros is also a member of the Arab League.[4]

Minority languages

Malagasy

According to Ethnologue, Malagasy is a minority language spoken in the Comoros.[17] A dialect of Malagasy called Shibushi is spoken by an estimated 39,000 people in the Comoros Islands.[18] Traces of Malagasy speakers predominantly reside in the islands of Mayotte and Moheli manifesting as small populations of Malagasy-speaking villages[6] The small Malagasy-speaking communities originated from the late 18th century to the early 19th century, with migrants from Madagascar settling in the Comoros. This was the result of the slave trades in Madagascar occurring at this time, as well as the periods of Malagasy rulers on the islands.[6] The presence of the Malagasy language has also influenced the surrounding languages in the archipelago.[3] For example, there is a variant of the Shimwali dialect in Moheli that heavily borrows Malagasy vocabulary.[3]

Swahili

Historically, Swahili served as the lingua franca of the Comoros, used for trade with the Arabic Peninsula, the East African Coast.[7] As a Bantu language, Swahili shares similarities with the Comorian language and is estimated to be spoken by 1% of the population.[7][19] Much of the early history of the Comoros is written in Swahili, using the Arabic script.[4] Many ancient Comorian poems and songs written in Swahili detail key historical events such as the slave trade, and the various battles between the Sultans who once ruled the Comoros.[4] Swahili played a major role for the struggle for independence in the 1960s when Comorians living in Tanzania would support independence by broadcasting messages via radio in Comorian and Swahili to Comorians living in French-colonised Comoros.[19] Kiunguja, a dialect of Swahili, is also spoken in the Comoros, particularly in Grande Comore Islands. This was the result of the migration to the Comoros from Zanzibar in Tanzania during the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution.[6]

Uses

In government and commerce, French is the most widely used language.[6] Since colonisation, education in the Comoros has largely followed the French model where French is used as the language of instruction.[4] A strict French monolingual policy was historically enforced for public schools.[4] Arabic is largely confined to religious, Quranic education and is introduced as early as the age of four or five.[4] In Comorian society, religious parents often insist on their children learning Arabic in Quranic schools before learning French in the public school system.[4] The national education policy has also reinforced the role of French and Arabic as languages of instruction from primary through tertiary education, while Comorian is permitted at the preschool level.[4] French and Arabic are also featured on the Comorian Franc, the official currency of the Comoros. The languages of media are predominantly French and Arabic.[16] Newspapers are only published in two languages, as in the Arabic language Al Watany, and the independent, French language, l’Archipel.[16] On social media, French is the predominant language, with 100% of Comorians in 2014 reported to have used French as their language on Facebook.[20] Historically, French colonial planters and government officials used French to write personal and place names. This has influenced the spelling of place names on maps in the Comoros, many streets use French signage.[4] Each island also holds a French and a Comorian name.[4]

Use of Comorian

Outside of administration, education and commerce, French and Arabic are not widely spoken.[11] Instead, Comorian is the most widely spoken language, confined largely to informal and oral purposes.[2] This is because, during the French colonial period, Comorian language use was forbidden in schools as it was not considered a suitable medium of instruction.[4] Under the French model of education, Comorian language use by students were often met with severe punishments.[4] The use of Comorian is also restricted by the lack of stable writing form that has complicated Comorian language use in education.[12] Despite the lack of written standard, Comorian is still used for administrative purposes to a limited extent.[4] In October 1974, the French National Assembly passed a resolution, requiring that the referendum bill be published in both French and Comorian and the Arabic script was used for the Comorian documentation.[4] Comorian is also becoming increasingly present in education, with many schools teaching grammar on the local Comorian dialects.[4] In January 1978, the Comorian government had reformed primary schools to cater to religious education in Arabic and nursery education in Comorian.[4] Since 2009, there has been an ongoing debate in the Comorian Government for Comorian as a language of instruction alongside French and Arabic.[12] Amongst the different variants of Comorian, the Shingazidja is considered the most commonly used dialect, due to the population of Grande Comore Island being the largest in the archipelago.[3] Shingazidja was used for the 1974 French and Comorian language referendum bill.[3] The preference towards Shingazidja however, has contributed to the growing language disunity amongst the Comorian variants.[9][2]

Multilingualism

Multilingualism is prevalent in the Comoros with a diverse language repertoire.[19][21] The potential language repertoire of a Comorian can consist of at least one of the Comorian dialects, French, Arabic, Malagasy and Swahili.[19] Most of the population speaks at least two of the three official languages in addition to the minority languages.[22] Code-switching is frequently used for socialising purposes, in particular, with the Comorian youth.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ "Comoros's Constitution of 2001 with Amendments through 2009"(PDF). Retrieved 18 May 2020

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Walker, Iain (2011). "What Came First, The Nation or the State? Political Process in the Comoro Islands". Africa. 77 (4): 586. doi:10.3366/afr.2007.77.4.582. ISSN 0001-9720.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Joseph Ottenheimer, Harriet (2001). "Spelling Shinzwani: Dictionary construction and orthographic choice in the Comoro Islands". Written Language & Literacy. 4 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1075/wll.4.1.03jos. ISSN 1387-6732.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 Bakar, Abdourahim Said (1988). "Small Island Systems: a case study of the Comoro Islands". Comparative Education. 24 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1080/0305006880240203. ISSN 0305-0068.

- ↑ "Union des Comores". Tlfq.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Ottenheimer, M. (1971). Domoni: Formal Analysis And Ethnography Of A Comoro Island Community (Order No. 7120225). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (302537456).

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Ottenheimer, Martin; Ottenheimer, Harriet Joseph (1976). "The Classification of the Languages of the Comoro Islands". Anthropological Linguistics. 8 (9): 405-406.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (2016). Africa : an encyclopedia of culture and society. Santa Barbara, California. pp. 260–264. ISBN 978-1-59884-665-2. OCLC 900016532.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Ottenheimer, Harriet J. (2012). "Ideology and Orthography". Études Océan Indien (48). doi:10.4000/oceanindien.1521. ISSN 0246-0092

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Ottenheimer, Martin; Ottenheimer, Harriet Joseph (1976). "The Classification of the Languages of the Comoro Islands". Anthropological Linguistics. 8 (9): 408-409.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 The linguistic typology and representation of African languages. Mugane, John M., Annual Conference on African Linguistics (33rd : 2002 : Ohio University). Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press. 2003. ISBN 1-59221-155-0. OCLC 53881176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 The impact of language policy and practice on children’s learning: Evidence from Eastern and Southern Africa (PDF) (Report). UNICEF. p. 26.

- ↑ Estimation des populations francophones dans le monde en 2018 (PDF) (in French). ODSEF. 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2020

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sellström, Tor (2015-05-26). "Africa In the Indian Ocean. Islands Ebb and Flow". doi10.1163/9789004292499 ISBN 978-90-04-29249-9.

- ↑ Full, W. (2006), "Comoros: Language Situation", Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Elsevier, pp. 685–686, doi:10.1016/b0-08-044854-2/04879-3, ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1, retrieved 2020-05-18

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Arab media : globalization and emerging media industries. Mellor, Noha, 1969-, ʻĀyish, Muḥammad ʻIṣām., Dajani, Nabil H., Rinnawi, Khalil. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-7456-4534-6. OCLC 731216190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Comoros at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- ↑ Frawley, William (2003). International encyclopedia of linguistics. Frawley, William, 1953- (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-19-513977-1. OCLC 51478240.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Waldburger, Daniela (2013). The Plurilingual Repertoire of the Comorian Community in Marseille: Remarks on Status and Function Based on Selected Sociolinguistic Biographies (PDF). pp. 262–263. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ "Citizen Engagement and Public Services in the Arab World: The Potential of Social Media" (PDF). Mohammed Bin Rashid School of Government. 25 June 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ottenheimer, Harriet, 1941- (January 2018). The anthropology of language : an introduction to linguistic anthropology. Pine, Judith M. S. (Fourth ed.). Boston, MA. ISBN 978-1-337-57100-5. OCLC 1020345071.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Frawley, William (2003). International encyclopedia of linguistics (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513977-1. OCLC 51478240.