Llywelyn ab Iorwerth

| Llywelyn ab Iorwerth | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Aberffraw Lord of Snowdon | |

| |

| King of Gwynedd | |

| Reign | 1195–1240 |

| Predecessor | Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd |

| Successor | Dafydd ap Llywelyn |

| Born | c. 1173[1] Dolwyddelan |

| Died | 11 April 1240 Aberconwy Abbey |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Joan, Lady of Wales |

| Issue |

|

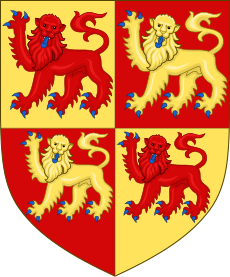

| House | Aberffraw |

| Father | Iorwerth Drwyndwn |

| Mother | Marared ferch Madog |

Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (pronounced [ɬəˈwɛlɪn ab ˈjɔrwɛrθ], c. 1173 – 11 April 1240), also known as Llywelyn the Great (Welsh: Llywelyn Fawr, [ɬəˈwɛlɪn vaʊ̯r]; Latin: Leolinus Magnus), was a medieval Welsh ruler. He succeeded his uncle, Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd, as King of Gwynedd in 1195. By a combination of war and diplomacy, he dominated Wales for 45 years. During Llywelyn's childhood, Gwynedd was ruled by two of his uncles, who split the kingdom between them, following the death of Llywelyn's grandfather, Owain Gwynedd, in 1170. Llywelyn had a strong claim to be the legitimate ruler and began a campaign to win power at an early age. He was sole ruler of Gwynedd by 1200 and made a treaty with King John of England that year. Llywelyn's relations with John remained good for the next ten years. He married John's natural daughter Joan in 1205, and when John arrested Gwenwynwyn of Powys in 1208, Llywelyn took the opportunity to annex southern Powys. In 1210, relations deteriorated, and John invaded Gwynedd in 1211. Llywelyn was forced to seek terms and to give up all lands east of the River Conwy but was able to recover them the following year in alliance with the other Welsh princes. He allied himself with the barons who forced John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. By 1216, he was the dominant power in Wales, holding a council at Aberdyfi that year to apportion lands to the other princes. Following King John's death, Llywelyn concluded the Treaty of Worcester with his successor, Henry III, in 1218. During the next fifteen years, Llywelyn was frequently involved in fights with Marcher lords and sometimes with the king, but also made alliances with several major powers in the Marches. The Peace of Middle in 1234 marked the end of Llywelyn's military career, as the agreed truce of two years was extended year by year for the remainder of his reign. He maintained his position in Wales until his death in 1240 and was succeeded by his son Dafydd ap Llywelyn.

Early life

Llywelyn was born about 1173, the son of Iorwerth Drwyndwn and the grandson of Owain Gwynedd, who had been ruler of Gwynedd until his death in 1170.[2] He was probably born at Dolwyddelan the royal manor of Nantconwy,[3] though not in the present Dolwyddelan Castle, which was built by Llywelyn himself. He may have been born in the old castle which occupied a rocky knoll on the valley floor.[4][ll 1] Little is known about his father, Iorwerth Drwyndwn, who died when Llywelyn was an infant. There is no record of Iorwerth having taken part in the power struggle between some of Owain Gwynedd's other sons following Owain's death, although he was the eldest surviving son. There is a tradition that he was disabled or disfigured in some way that excluded him from power.[5] John Edward Lloyd states that Iorwerth was killed in battle at Pennant Melangell, in Powys, in 1174 during the wars deciding the succession following the death of his father.[3][6] By 1175, Gwynedd had been divided between two of Llywelyn's uncles. Dafydd ab Owain held the area east of the River Conwy and Rhodri ab Owain held the west. Dafydd and Rhodri were the sons of Owain by his second marriage to Cristin verch Goronwy. This marriage was not considered valid by the church as Cristin was Owain's first cousin, a degree of relationship which according to Canon law prohibited marriage. The chronicler Gerald of Wales refers to Iorwerth Drwyndwn as the only legitimate son of Owain Gwynedd.[7][ll 2] Following Iorwerth's death, Llywelyn was, at least in the eyes of the church, the legitimate claimant to the throne of Gwynedd.[7] Llywelyn's mother was Marared, occasionally anglicised to Margaret, daughter of Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys. There is evidence that after Iorwerth's death Marared married into the Corbet family of Caux in Shropshire, and Llywelyn may have spent part of his childhood there.[8] There is in existence a grant of land from Llywelyn ab Iorwerth to the monastery of Wigmore, in which Llywelyn indicates his mother was a member of the house of Corbet.[9]

Rise to power 1188–1199

In his account of his journey around Wales in 1188, Gerald mentions that the young Llywelyn was already in arms against his uncles Dafydd and Rhodri:

Owen, son of Gruffyth, prince of North Wales, had many sons, but only one legitimate, namely, Iorwerth Drwyndwn, which in Welsh means "flat-nosed", who had a son named Lhewelyn. This young man, being only twelve years of age, began, during the period of our journey, to molest his uncles David and Roderic, the sons of Owen by Christiana, his cousin-german; and although they had divided amongst themselves all North Wales, except the land of Conan, and although David, having married the sister of king Henry II, by whom he had one son, was powerfully supported by the English, yet within a few years the legitimate son, destitute of lands or money (by the aid of divine vengeance), bravely expelled from North Wales those who were born in public incest, though supported by their own wealth and by that of others, leaving them nothing but what the liberality of his own mind and the counsel of good men from pity suggested: a proof that adulterous and incestuous persons are displeasing to God.[7][ll 3]

In 1194, with the aid of his cousins Gruffudd ap Cynan[ll 4] and Maredudd ap Cynan, he defeated Dafydd at the Battle of Aberconwy at the mouth of the River Conwy.[3] Rhodri died in 1195, and his lands west of the Conwy were taken over by Gruffudd and Maredudd, while Llywelyn ruled the territories taken from Dafydd east of the Conwy.[10] In 1197, Llywelyn captured Dafydd and imprisoned him. A year later Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury, persuaded Llywelyn to release him, and Dafydd retired to England, where he died in May 1203. Wales was divided into Pura Wallia, the areas ruled by the Welsh princes, and Marchia Wallia, ruled by the Anglo-Norman barons. Since the death of Owain Gwynedd in 1170, Rhys ap Gruffydd had made the southern kingdom of Deheubarth the strongest of the Welsh kingdoms, and had established himself as the leader of Pura Wallia. After Rhys died in 1197, fighting between his sons led to the splitting of Deheubarth between warring factions. Gwenwynwyn, prince of Powys Wenwynwyn, tried to take over as leader of the Welsh princes, and in 1198, raised a great army to besiege Painscastle, which was held by the troops of William de Braose, 4th Lord of Bramber. Llywelyn sent troops to help Gwenwynwyn, but in August Gwenwynwyn's force was attacked by an army led by the justiciar, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, 1st Earl of Essex, and heavily defeated.[11] Gwenwynwyn's defeat gave Llywelyn the opportunity to establish himself as the leader of the Welsh. In 1199, he captured the important castle of Mold, Flintshire and was apparently using the title "prince of the whole of North Wales" (Latin: tocius norwallie princeps).[12] Llywelyn was probably not in fact master of all Gwynedd at this time since it was his cousin Gruffudd ap Cynan who promised homage to King John for Gwynedd in 1199.[13]

Reign as Prince of Gwynedd

Consolidation 1200–1209

Gruffudd ap Cynan ab Owain Gwynedd died in 1200 and left Llywelyn the undisputed ruler of Gwynedd. In 1201, he took Eifionydd and Llŷn from Maredudd ap Cynan on a charge of treachery.[13] In July, the same year Llywelyn concluded a treaty with King John of England. This is the earliest surviving written agreement between an English king and a Welsh ruler, and under its terms, Llywelyn was to swear fealty and do homage to the king. In return, it confirmed Llywelyn's possession of his conquests and allowed cases relating to lands claimed by Llywelyn to be heard under Welsh law.[14] Llywelyn made his first move beyond the borders of Gwynedd in August 1202 when he raised a force to attack Gwenwynwyn ab Owain Cyfeiliog of Powys, who was now his main rival in Wales. The clergy intervened to make peace between Llywelyn and Gwenwynwyn and the invasion was called off. Elise ap Madog, lord of Penllyn, had refused to respond to Llywelyn's summons to arms and was stripped of almost all his lands by Llywelyn as punishment.[15] Llywelyn consolidated his position in 1205 by marrying Joan, Lady of Wales, the natural daughter of King John.[3] He had previously been negotiating with Pope Innocent III for leave to marry his uncle Rhodri's widow, daughter of Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles. However, this proposal was dropped.[16][ll 5] In 1208, Gwenwynwyn of Powys fell out with King John who summoned him to Shrewsbury in October and then arrested him and stripped him of his lands. Llywelyn took the opportunity to annex southern Powys and northern Ceredigion and rebuild Aberystwyth Castle.[17] In the summer of 1209 he accompanied John on a campaign against King William the Lion, Scotland.[18]

Setback and recovery 1210–1217

In 1210, relations between Llywelyn and King John deteriorated. John Edward Lloyd suggests that the rupture may have been due to Llywelyn forming an alliance with William de Braose, 4th Lord of Bramber, who had fallen out with the king and had been deprived of his lands.[19] While John led a campaign against de Braose and his allies in Ireland, an army led by Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, and Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, invaded Gwynedd. Llywelyn destroyed his own castle at Deganwy and retreated west of the River Conwy. The Earl of Chester rebuilt Deganwy, and Llywelyn retaliated by ravaging the Earl's lands.[20][21] John sent troops to help restore Gwenwynwyn to the rule of southern Powys. In 1211, John invaded Gwynedd with the aid of almost all the other Welsh princes, planning according to Brut y Tywysogion "to dispossess Llywelyn and destroy him utterly".[22] The first invasion was forced to retreat, but in August that year John invaded again with a larger army, crossed the River Conwy and penetrated Snowdonia.[23] Bangor was burnt by a detachment of the royal army and the Bishop of Bangor captured. Llywelyn was forced to come to terms, and by the advice of his council sent his wife Joan to negotiate with the king, her father.[24] Joan was able to persuade her father not to dispossess her husband completely, but Llywelyn lost all his lands east of the River Conwy.[25] He also had to pay a large tribute in cattle and horses and to hand over hostages, including his illegitimate son Gruffudd and was forced to agree that if he died without a legitimate heir by Joan, all his lands would revert to the king.[26] This was the low point of Llywelyn's reign, but he quickly recovered his position. The other Welsh princes, who had supported King John against Llywelyn, soon became disillusioned with John's rule and changed sides. Llywelyn formed an alliance with Gwenwynwyn of Powys and the two main rulers of Deheubarth, Maelgwn ap Rhys and Rhys Gryg, and rose against John. They had the support of Pope Innocent III, who had been engaged in a dispute with John for several years and had placed his kingdom under an interdict. Innocent III released Llywelyn, Gwenwynwyn and Maelgwn from all oaths of loyalty to John and lifted the interdict in the territories which they controlled. Llywelyn was able to recover all Gwynedd apart from the castles of Deganwy and Rhuddlan within two months in 1212.[27] John planned another invasion of Gwynedd in August 1212. According to one account, he had just commenced by hanging some of the Welsh hostages given the previous year when he received two letters. One was from his daughter Joan, Llywelyn's wife, the other from William I of Scotland (William the Lion), and both warned him in similar terms that if he invaded Wales his magnates would seize the opportunity to kill him or hand him over to his enemies.[28] The invasion was abandoned, and in 1213, Llywelyn took the castles of Deganwy and Rhuddlan.[29] Llywelyn made an alliance with Philip II Augustus of France,[30] then allied himself with the barons who were in rebellion against John, marching on Shrewsbury and capturing it without resistance in 1215.[31] When John was forced to sign Magna Carta,[3] Llywelyn was rewarded with several favourable provisions relating to Wales, including the release of his son, Gruffudd, who had been a hostage since 1211.[32] The same year, Ednyfed Fychan was appointed seneschal of Gwynedd and was to work closely with Llywelyn for the remainder of his reign.[33] Llywelyn had now established himself as the leader of the independent princes of Wales, and in December 1215, led an army which included all the lesser princes to capture the castles of Carmarthen, Kidwelly, Llanstephan, Cardigan and Cilgerran. Another indication of his growing power was that he was able to insist on the consecration of Welshmen to two vacant sees that year, Iorwerth, as Bishop of St Davids, and Cadwgan of Llandyfai, as Bishop of Bangor.[34] In 1216, Llywelyn held a council at Aberdyfi to adjudicate on the territorial claims of the lesser princes, who affirmed their homage and allegiance to Llywelyn. J. Beverley Smith comments: "The leader in military alliance assumed the role of lord, his erstwhile allies were now his vassals."[35] Gwenwynwyn of Powys changed sides again that year and allied himself with King John. Llywelyn called up the other princes for a campaign against him and drove him out of southern Powys once more.[3] Gwenwynwyn died in England later that year, leaving an underage heir. King John also died that year, and he also left an underage heir in King Henry III with a minority government set up in England.[36] In 1217, Reginald de Braose of Brecon and Abergavenny, who had been allied to Llywelyn and married his daughter, Gwladus Ddu, was induced by the English crown to change sides. Llywelyn responded by invading his lands, first threatening Brecon, where the burgesses offered hostages for the payment of 100 marks, then heading for Swansea where Reginald de Braose met him to offer submission and to surrender the town. He then continued westwards to threaten Haverfordwest where the burgesses offered hostages for their submission to his rule or the payment of a fine of 1,000 marks.[37][38]

Treaty of Worcester and border campaigns 1218–1229

Following King John's death Llywelyn concluded the Treaty of Worcester with his successor Henry III in 1218.[3] This treaty confirmed him in possession of all his recent conquests. From then until his death Llywelyn was the dominant force in Wales, though there were further outbreaks of hostilities with marcher lords, particularly the Marshal family and Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent, and sometimes with the king. Llywelyn built up marriage alliances with several of the Marcher families. One daughter, Gwladus Ddu ("Gwladus the Dark"), was already married to Reginald de Braose of Brecon and Abergavenny, but with Reginald an unreliable ally Llywelyn married another daughter, Marared, to John de Braose of Gower, Reginald's nephew. He found a loyal ally in Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, whose nephew and heir, John of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon, married Llywelyn's daughter Elen ferch Llywelyn in about 1222. Following Reginald de Braose's death in 1228, Llywelyn also made an alliance with the powerful Roger Mortimer of Wigmore when Gwladus Ddu married as her second husband Ralph de Mortimer.[39] Llywelyn was careful not to provoke unnecessary hostilities with the crown or the Marcher lords; for example, in 1220, he compelled Rhys Gryg to return four commotes in South Wales to their previous Anglo-Norman owners.[40] He built a number of castles to defend his borders, most thought to have been built between 1220 and 1230. These were the first sophisticated stone castles in Wales; his castles at Criccieth, Deganwy, Dolbadarn, Dolwyddelan and Castell y Bere are among the best examples.[41] Llywelyn also appears to have fostered the development of quasi-urban settlements in Gwynedd to act as centres of trade.[42] Hostilities broke out with William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke in 1220. Llywelyn destroyed the castles of Narberth and Wiston, burnt the town of Haverfordwest and threatened Pembroke Castle, but agreed to abandon the attack on payment of £100. In early 1223, Llywelyn crossed the border into Shropshire and captured Kinnerley and Whittington castles. The Marshals took advantage of Llywelyn's involvement here to land near St David's in April with an army raised in Ireland and recaptured Cardigan and Carmarthen without opposition. The Marshals' campaign was supported by a royal army which took possession of Montgomery.[3] Llywelyn came to an agreement with the king at Montgomery in October that year. Llywelyn's allies in South Wales were given back lands taken from them by the Marshals and Llywelyn himself gave up his conquests in Shropshire.[43] In 1228, Llywelyn was engaged in a campaign against Hubert de Burgh, who was Justiciar of England and Ireland and one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. Hubert had been given the lordship and castle of Montgomery by the king and was encroaching on Llywelyn's lands nearby. The king raised an army to help Hubert, who began to build another castle in the commote of Ceri. However, in October the royal army was obliged to retreat and Henry agreed to destroy the half-built castle in exchange for the payment of £2,000 by Llywelyn. Llywelyn raised the money by demanding the same sum as the ransom of William de Braose, Lord of Abergavenny, whom he had captured in the fighting.[44]

Marital problems 1230

Following his capture, William de Braose decided to ally himself to Llywelyn, and a marriage was arranged between his daughter Isabella and Llywelyn's heir, Dafydd ap Llywelyn. At Easter 1230, William visited Llywelyn's court. During this visit, he was found in Llywelyn's chamber together with Llywelyn's wife Joan. On 2 May, de Braose was hanged; Joan was placed under house arrest for a year. The Brut y Tywysogion chronicler commented:

- "That year William de Braose the Younger, Lord of Abergavenny, was hanged by the lord Llywelyn in Gwynedd after he had been caught in Llywelyn's chamber with the king of England's daughter, Llywelyn's wife."[45]

A letter from Llywelyn to William's wife, Eva Marshal, written shortly after the execution enquires whether she still wishes the marriage between Dafydd and Isabella to take place.[46] The marriage did go ahead, and the following year Joan was forgiven and restored to her position as princess. Until 1230, Llywelyn had used the title princeps Norwalliæ "Prince of North Wales", but from that year he changed his title to "Prince of Aberffraw and Lord of Snowdon".[3][ll 6] He was, however, more concerned with the reality of power rather than its appearance. He never claimed or used the title "Prince of Wales" despite his authority extending over other rulers in Wales.[47]

Final campaigns and the Peace of Middle 1231–1240

In 1231, there was further fighting. Llywelyn was becoming concerned about the growing power of Hubert de Burgh. Some of his men had been taken prisoner by the garrison of Montgomery and beheaded, and Llywelyn responded by burning Montgomery, Powys, New Radnor, Hay, and Brecon before turning west to capture the castles of Neath and Kidwelly. He completed the campaign by recapturing Cardigan Castle.[48] King Henry retaliated by launching an invasion and built a new castle at Painscastle, but was unable to penetrate far into Wales.[49] Negotiations continued into 1232 when Hubert was removed from office and later imprisoned. Much of his power passed to Peter de Rivaux, including control of several castles in south Wales. William Marshal had died in 1231, and his brother Richard had succeeded him as Earl of Pembroke. In 1233, hostilities broke out between Richard Marshal and Peter de Rivaux, who was supported by the king. Llywelyn made an alliance with Richard, and in January 1234 the earl and Llywelyn seized Shrewsbury.[3] Richard was killed in Ireland in April, but the king agreed to make peace with the insurgents.[50] The Peace of Middle, agreed on 21 June, established a truce of two years with Llywelyn, who was allowed to retain Cardigan and Builth.[3] This truce was renewed year by year for the remainder of Llywelyn's reign.[51]

Death and aftermath

Arrangements for the succession

In his later years, Llywelyn devoted much effort to ensuring that his only legitimate son, Dafydd, would follow him as ruler of Gwynedd and amended Welsh law as followed in Gwynedd.[52][ll 7] Llywelyn's amendment to Welsh law favouring legitimate children in a Church sanctioned marriage mirrored the earlier efforts of the Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, in designating Gruffydd ap Rhys II as his heir over those of his illegitimate eldest son, Maelgwn ap Rhys. In both cases, favouring legitimate children born in a Church sanctioned marriage would facilitate better relations between their sons and the wider Anglo-Norman polity and Catholic Church by removing any "stigma" of illegitimacy. Dafydd's older but illegitimate brother, Gruffudd, was therefore excluded as the primary heir of Llywelyn, though would be given lands to rule. This was a departure from Welsh custom, which held that the eldest son was his father's heir regardless of his parents' marital status.[54][ll 8][ll 9] In 1220, Llywelyn induced the minority government of King Henry to acknowledge Dafydd as his heir.[57] In 1222, he petitioned Pope Honorius III to have Dafydd's succession confirmed. The original petition has not been preserved, but the Pope's reply refers to the "detestable custom... in his land whereby the son of the handmaiden was equally heir with the son of the free woman and illegitimate sons obtained an inheritance as if they were legitimate." The Pope welcomed the fact that Llywelyn was abolishing this custom.[58] In 1226, Llywelyn persuaded the Pope to declare his wife Joan, Dafydd's mother, to be a legitimate daughter of King John, again in order to strengthen Dafydd's position, and in 1229, the English crown accepted Dafydd's homage for the lands he would inherit from his father.[3][57] In 1238, Llywelyn held a council at Strata Florida Abbey where the other Welsh princes swore fealty to Dafydd.[57] Llywelyn's original intention had been that they should do homage to Dafydd, but the king wrote to the other rulers forbidding them to do homage.[59] Additionally, King Llywelyn arranged for his son Dafydd to marry Isabella de Braose, eldest daughter of William de Braose. As William de Braose had no male heir, Llywelyn strategized that the vast de Braose holdings in South Wales would pass to the heir of Dafydd with Isabella. Gruffudd was given an appanage in Meirionnydd and Ardudwy but his rule was said to be oppressive, and in 1221 Llywelyn stripped him of these territories.[60] In 1228, Llywelyn imprisoned him, and he was not released until 1234. On his release, he was given part of Llŷn to rule. His performance this time was apparently more satisfactory, and by 1238, he had been given the remainder of Llŷn and a substantial part of Powys.[61]

Death and the transfer of power

Joan died in 1237 and Llywelyn appears to have suffered a paralytic stroke the same year.[62] From this time on, his heir Dafydd took an increasing part in the rule of the kingdom. Dafydd deprived his half-brother Gruffudd of the lands given him by Llywelyn and later seized him and his eldest son Owain and held them in Criccieth Castle. The chronicler of Brut y Tywysogion records that in 1240, "the lord Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Prince of Wales, son of Owain Gwynedd, a second Achilles, died having taken on the habit of religion at Aberconwy, and was buried honourably."[63] Llywelyn died at the Cistercians abbey of Aberconwy, which he had founded and was buried there.[3] This abbey was later moved to Maenan, becoming the Maenan Abbey, near Llanrwst, and Llywelyn's stone coffin can now be seen in St Grwst's Church, Llanrwst. Among the poets who lamented his passing was Einion Wan:

True lord of the land – how strange that today

He rules not o'er Gwynedd;

Lord of nought but the piled up stones of his tomb,

Of the seven-foot grave in which he lies.[ll 10]

Dafydd succeeded Llywelyn as Prince of Gwynedd, but King Henry was not prepared to allow him to inherit his father's position in the remainder of Wales. Dafydd was forced to agree to a treaty greatly restricting his power and was also obliged to hand his half-brother Gruffudd over to the king, who now had the option of using him against Dafydd. Gruffudd was killed attempting to escape from the Tower of London in 1244. This left the field clear for Dafydd, but Dafydd himself died with illegitimate and underage issue in 1246 and was eventually succeeded by his nephew, Gruffudd's son, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Historical assessment

Llywelyn dominated Wales for more than 40 years and was one of only two Welsh rulers to be called "the Great", the other being his ancestor Rhodri the Great (Rhodri Mawr). The first person to give Llywelyn the title "the Great" seems to have been his near contemporary, the English chronicler Matthew Paris.[65][ll 11] John Edward Lloyd gave the following assessment of Llywelyn:

"Among the chieftains who battled against the Anglo-Norman power his place will always be high if not indeed the highest of all, for no man ever made better or more judicious use of the native force of the Welsh people for adequate national ends; his patriotic statesmanship will always entitle him to wear the proud style of Llywelyn the Great".[64]

David Moore gives a different view:

"When Llywelyn died in 1240, his principatus of Wales rested on shaky foundations. Although he had dominated Wales, exacted unprecedented submissions and raised the status of the Prince of Gwynedd to new heights, his three major ambitions – a permanent hegemony, its recognition by the king, and its inheritance in its entirety by his heir – remained unfulfilled. His supremacy, like that of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, had been merely personal in nature, and there was no institutional framework to maintain it either during his lifetime or after his death."[67]

Children

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Llywelyn married Joan, natural daughter of John, King of England, in 1205. Llywelyn and Joan had three identified children in the records, but in all probability had more, as Llywelyn's children were fully recognized during his marriage to Joan whilst his father-in-law, King John, was alive. Little is known of Llywelyn's mistress, Tangwystl Goch. His union with her was not recognised by the church. She was the daughter of Llywarch "Goch."[3][68][69] After Joan's death, Llywelyn took Eva the daughter of Fulk FitzWarin as his wife. As well as children from his marriage to Joan, he also had children out of wedlock to a Welsh concubine.[70] The following are recorded in contemporary or near-contemporary records: Children by Joan:[3][71][69]

- Dafydd ap Llywelyn (c. 1212–1246) married Isabella de Braose;

- Gwladus Ddu (1206–1251);[72][ll 12]

- Elen ferch Llywelyn (1207–1253), married (1) John of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and (2) Robert II de Quincy;

- Susanna ferch Llywelyn (died after November 1228);[69][ll 13]

- Marared (Margaret) ferch Llywelyn (died after 1268), married John de Braose in 1219,[75][69] and had issue.[76] Secondly (c. 1232) Walter III de Clifford;[3]

- Elen (the younger) ferch Llywelyn, Countess of Mar, possibly identical with Susanna (born before 1230; died after 16 February 1295).[77][ll 14][ll 15]

Children by Tangwystl Goch,[78] (died c. 1198):[citation needed]

- Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, became a hostage of King John;[79][ll 16]

- Gwenllian, married William de Lacy, son of Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath.[3][81][82]

Children whose parentage is uncertain:[citation needed]

- Angharad ferch Llywelyn (c. 1212–1256), probable daughter by Joan; married Maelgwn Fychan;[citation needed]

- Tegwared y Bais Wen ap Llywelyn (c. 1215), a son by a woman named Crysten in some sources, a possible twin of Angharad.[83][84]

Family tree

The family tree of Llywelyn the Great's lineal descendants from his birth in the late 12th century until the end of the family dynasty of Gwynedd in the late 14th century:[85]

| Llywelyn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd ap Llywelyn 1200–1244 | Dafydd ap Llywelyn 1212–1240–1246 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Goch ap Gruffudd d. 1282 | Llywelyn ap Gruffudd 1223–1246–1282 | Dafydd ap Gruffudd 1238–1282–1283 | Rhodri ap Gruffudd 1230–1315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gwenllian of Wales 1282–1337 | Llywelyn ap Dafydd 1267–1283–1287 | Owain ap Dafydd 1275–1287–1325 | Tomas ap Rhodri 1300–1325–1363 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Lawgoch 1330–1378 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cultural allusions

A number of Welsh poems addressed to Llywelyn by contemporary poets such as Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr, Dafydd Benfras and Llywarch ap Llywelyn (better known under the nickname Prydydd y Moch) have survived. Very little of this poetry has been published in English translation.[ll 17] Llywelyn has continued to figure in modern Welsh literature. The play Siwan (1956, English translation 1960) by Saunders Lewis deals with the finding of William de Braose in Joan's chamber and his execution by Llywelyn. Another well-known Welsh play about Llywelyn is Llywelyn Fawr by Thomas Parry. Llywelyn is the main character or one of the main characters in several English-language novels:

- Raymond Foxall (1959) Song for a Prince: The Story of Llywelyn the Great covers the period from King John's invasion in 1211 to the execution of William de Braose.

- Sharon Kay Penman's (1985) Here Be Dragons is centred on the marriage of Llywelyn and Joan. Dragon's Lair (2003) by the same author features the young Llywelyn before he gained power in Gwynedd. Llywelyn further appears in Penman's novel Falls the Shadow (1988).

- Edith Pargeter (1960–1963) "The Heaven Tree Trilogy" features Llywelyn, Joan, William de Braose, and several of Llywelyn's sons as major characters.

- Gaius Demetrius (2006) Ascent of an Eagle tells the story of the early part of Llywelyn's reign.

The story of the faithful hound Gelert, owned by Llywelyn and mistakenly killed by him, is also considered to be fiction. "Gelert's grave" is a popular tourist attraction in Beddgelert but is thought to have been created by an 18th century innkeeper to boost the tourist trade. The tale itself is a variation on a common folktale motif.[ll 18]

Notes

- ↑ According to one genealogy, Llywelyn had a brother named Adda, but there is no other record of him.

- ↑ Maelgwn ab Owain Gwynedd was Iorwerth's full brother, but presumably he was dead by the time Giraldus wrote.

- ↑ Giraldus says that Llywelyn was only twelve years of age at this time, which would mean that he was born about 1176. However, most historians consider that he was born about 1173

- ↑ This Gruffudd ap Cynan should not be confused with Gruffudd ap Cynan the late 11th and early 12th century king of Gwynedd, Llywelyn's great-grandfather

- ↑ One letter from the Pope suggests that Llywelyn may have been married previously, to an unnamed sister of Earl Ranulph of Chester in about 1192, but there appears to be no confirmation of this.

- ↑ The version of the Welsh laws preserved in Llyfr Iorwerth, compiled in Gwynedd during Llywelyn's reign, claims precedence for the ruler of Aberffraw, the ancient court, over the rulers of the other Welsh kingdoms. See Aled Rhys William (1960) Llyfr Iorwerth: a critical text of the Venedotian code of mediaeval Welsh law

- ↑ A history of Wales[53] 2004 reprint, also look up, pp. 347, 369 and note 64, 82, 164

- ↑ According to Hubert Lewis, though not explicitly codified as such, the Edling or Heir apparent, was by convention, custom and practice the eldest son of the lord and entitled to inheirit the position and title as "head of the family" from the father. Effectively primogeniture with local variations. However, all sons were provided for out of the lands of the father and in certain circumstances, so too were daughters. Additionally, sons could claim maternal patrimony through their mother in certain circumstances.

- ↑ There was provision in Welsh law for the selection of a single edling or heir by the ruler, for the succession which created a family struggle.[55] For a discussion of this, see Stephenson.[56]

- ↑ Translated by Lloyd [64]

- ↑ Quote from Rolls Series [66]

- ↑ She married (1) Reginald de Braose and (2) Ralph de Mortimer,[72] with whom she had 3 sons including Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Mortimer of Wigmore, and a daughter.[73]

- ↑ King Henry III of England granted the upbringing of "L. princeps Norwallie et Johanna uxor sua et... soror nostra Susannam filiam suam" to "Nicholao de Verdun et Clementie uxori sue" by order dated 24 November 1228. Her birth date is estimated on the assumption that Susanna was under marriageable age, but older than an infant, at the time. It has been suggested that this Clemence, wife of Nicholas of Verdun was her maternal grandmother and that Susanna was the daughter of Llywelyn who married Máel Coluim II, Earl of Fife in 1230, and was the mother of his children, including Colban, Earl of Fife;[74]

- ↑ She married firstly Máel Coluim II, Earl of Fife,[77] son of Duncan Macduff of Fife and wife Alice Corbet, and secondly (after 1266) Domhnall I, Earl of Mar (son of William, Earl of Mar and first wife Elizabeth Comyn of Buchan).

- ↑ Elen and Domhall's daughter, Isabella of Mar, married Robert the Bruce and had one child by him, Marjorie Bruce, who was the mother of the first Stewart monarch, Robert II of Scotland. There is, however, a genealogical problem as the Elen who was widowed in 1266 seems to have been too young to be the same woman who married Máel Coluim II in 1230. Her older children with Domhall came of age in the 1290s. If they were the same person, this would have placed her childbearing years way past her 50s. As a solution, it has been later claimed that she was the daughter of Dafydd ap Llywelyn instead of Llywelyn himself. Nevertheless, this is not corroborated by her wedding date of 1230. Alternatively, British medievalist Kathryn Hurlock proposes that Susanna was the daughter Llywelyn who married Máel Coluim II, and that she predeceased him, which would make his widow Elen an entirely different person, unrelated to Llywelyn the Great and his family.[74]

- ↑ (c. 1196–1244) He was Llywelyn's eldest son. He married Senena, daughter of Caradoc ap Thomas of Anglesey. Their sons included Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, who for a period occupied a position in Wales comparable to that of his grandfather, and Dafydd ap Gruffudd who ruled Gwynedd briefly after his brother's death.[80]

- ↑ In praise of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth by Llywarch ap Llywelyn has been translated by Joseph P. Clancy (1970) in The earliest Welsh poetry.

- ↑ See D. E. Jenkins (1899). Beddgelert: Its Facts, Fairies and Folklore. Friends of St Mary's Church. pp. 56–74. ISBN 0953515214. for a detailed discussion of the Beddelgert dog legend.

References

- ↑ Brough, Gideon; Marsden, Richard (2011). "Llywelyn the Great (c. 1173–1240)". The Encyclopedia of War. doi:10.1002/9781444338232.wbeow367. ISBN 9781405190374.

- ↑ Bartrum 1966, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 (Pierce 1959)

- ↑ Lynch 1995, p. 156.

- ↑ Maund 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ Lloyd, J. E. (1959). The Dictionary of Welsh Biography Down to 1940. Blackwell Group. p. 417.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 The historical works of Giraldus Cambrensis, p. 403, at Google Books

- ↑ Maund 2006, p. 186.

- ↑ Caley 1830, pp. 497–498.

- ↑ Maund 2006, p. 187.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 585–586.

- ↑ Davies 1992, p. 239.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 (Moore 2005, p. 109)

- ↑ Davies 1992, p. 294.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 613–614.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 616–617.

- ↑ Davies 1992, pp. 229, 241.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 622–623.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, p. 631.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, p. 632.

- ↑ Maund 2006, p. 192.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 154.

- ↑ Maund 2006, p. 193.

- ↑ Williams 1860, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Gater, Dilys (1991). The Battles of Wales (1st ed.). Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-86381-178-4.

- ↑ Davies 1992, p. 295.

- ↑ Williams 1860, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Pryce 2005, p. 445.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 162.

- ↑ Moore 2005, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 165.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, p. 646.

- ↑ Dwnn, Lewys (1846). Samuel Rush Meyrick (ed.). The Heraldic Visitation of Wales, Vol. I,. p. xiv.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 167.

- ↑ Smith, J. Beverley (1998). Llywelyn ap Gruffudd: Prince of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7083-1474-6.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 649–651.

- ↑ Davies 1992, p. 242.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 652–653.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 645, 657–658.

- ↑ Davies 1992, p. 298.

- ↑ Lynch 1995, p. 135.

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales (Reprint ed.). Penguin Books. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-140-14581-6.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 661–663.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 667–670.

- ↑ Williams 1860, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Pryce 2005, pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Carpenter 2020, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 673–675.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, pp. 675–676.

- ↑ Powicke 1962, pp. 51–55.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, p. 681.

- ↑ John Edward Lloyd (2004). A history of Wales: from the Norman invasion to the Edwardian conquest (Reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. pp. 297, 362. ISBN 0760752419.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911.

- ↑ The Ancient Laws of Wales at Google Books

- ↑ Williams 1860, pp. 393–413.

- ↑ Stephenson 1984, pp. 138–141.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 (Davies 1992, p. 249)

- ↑ Pryce 2005, pp. 414–415.

- ↑ Carr 1995, p. 60.

- ↑ Williams 1860, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Lloyd 1911, p. 692.

- ↑ Stephenson 1984, p. xxii.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 198.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Lloyd 1911, p. 693.

- ↑ Paris, Matthew (1880). H. R. Luard (ed.). Chronica Majora. Vol. 5. London. p. 718.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Carr 1995.

- ↑ Moore 2005, p. 126.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, pp. 83, 86, 89–91.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 "JOAN (SIWAN) (died 1237), princess and diplomat". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ↑ (Lee)

- ↑ Turvey 2010, pp. 86, 90.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Turvey 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Ian Mortimer. "The Medieval Mortimer Family" (PDF). mortimer.co.uk. pp. 15–16.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Hurlock 2009.

- ↑ Williams 1860, p. 305.

- ↑ "BRAOSE BREOS, BRAUSE, BRIOUSE, BREWES, etc.) family.". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Hurlock 2009, pp. 352–355.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, p. 83.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, pp. 83, 85.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, pp. 99–105.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, pp. 83, 86.

- ↑ "LACY (DE) – lords of Ewyas, Weobley and Ludlow.". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ↑ Bartrum, Peter C. (1974). Welsh Genealogies, A.D. 300–1400. University of Wales Press.

- ↑ Mosley, Charles (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th ed., 3 vol. Delaware: Genealogical books. p. 4183.

- ↑ Turvey 2010, p. 13.

Sources

- Caley, John; Ellis, Henry; et al., eds. (1830). Monasticon Anglicanum. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. Monasticon Anglicanum (1846) at Google Books

- Hoare, Richard (1908). Giraldus Cambrensis: The Itinerary through Wales; Description of Wales. Everyman's Library. ISBN 0-460-00272-4.

Translated by R. C. Hoare

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 7–13.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "LLYWELYN ap IORWERTH". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pryce, Huw, ed. (2005). The Acts of Welsh Rulers, 1120–1283. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1897-3.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 831.

- Williams, John (1860). Brut y Tywysogion or The Chronicle of the Princes (Reprint ed.). London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts.

Caradoc of Llancarfan

- Bartrum, Peter C., ed. (1966). Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts. University of Wales Press.

- Carpenter, David (2020). Henry III: The Rise to Power and Personal Rule, 1207–1258. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300238358.

- Carr, A. D. (1995). Medieval Wales. Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-54773-1.

- Davies, R. R. (1992). The age of conquest : Wales, 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-167814-1. OCLC 1301799492.

- Hurlock, Kathryn (28 October 2009). "The Welsh Wife of Malcolm, Earl of Fife (d. 1266): An Alternative Suggestion". The Scottish Historical Review. 88 (2): 352–355. doi:10.3366/e0036924109000900.

- Jones-Pierce, T. (1962). Caernarvonshire Historical Society Transactions. Vol. 23.

Aber Gwyn Gregin

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911). A History of Wales, from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Vol. II (Reprint Vol. 2 of 2 ed.). Longmans, Green & Co. ISBN 978-1-334-06136-3.

- Lynch, Frances M. B. (1995). Gwynedd (A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales). The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-701574-6.

- Maund, Kari L. (2006). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords, and Princes (3rd ed.). Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2973-1.

- Moore, David (2005). The Welsh Wars of Independence. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3321-9.

- Powicke, Maurice (1962) [1953]. The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307 (Oxford History of England) (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821708-4.

- Stephenson, David (1984). The Governance of Gwynedd. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-0850-9. OL 22379507M.

- Turvey, Roger (2010). Twenty-One Welsh Princes. Conwy: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 9781845272692.

- Weis, Frederick Lewis (1992). Ancestral Roots of Certain American Colonists Who Came to America before 1700. Genealogical Publishing Com. pp. 27, 29A–27, 29A–28, 132C–29, 176B–27, 177, 184A–9, 236–237, 246–30, 254–28, 254–29, 260–31. ISBN 0806313676.

- Williams, G. A. (1964). "The Succession to Gwynedd, 1238–1247". archaeologydataservice.ac.uk: 393–413.

Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, XX (1962–1964)

External links

- "Llywelyn the Great" (PDF). cadw.gov.wales. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2021.

- "Llywelyn ab Iorwerth". bbc.co.uk.

- "Brut y Tywysogion". library.wales (First ed.). University of Wales Press.

Peniarth MS. 20

- Impression from Llywelyn's Great Seal

- A stone corbel from Llywelyn's castle at Deganwy, thought to be a likeness of Llywelyn Fawr, ab Iorwerth