History of Berlin

| History of Berlin |

|---|

| Coat of arms of the City of Berlin |

| Margraviate of Brandenburg (1157–1806) |

| Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918) |

| German Empire (1871–1918) |

| Free State of Prussia (1918–1947) |

| Weimar Republic (1919–1933) |

| Nazi Germany (1933–1945) |

| West Germany and East Germany (1945–1990) |

|

| Federal Republic of Germany (1990–present) |

| See also |

The history of Berlin starts with its foundation in the 12th century. It became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1237, and later of Brandenburg-Prussia, and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia grew about rapidly in the 18th and 19th centuries and formed the basis of the German Empire in 1871. The empire would survive until 1918 when it was defeated in World War I. After 1900 Berlin became a major world city, known for its leadership roles in science, the humanities, music, museums, higher education, government, diplomacy and military affairs. It also had a role in manufacturing and finance. During World War II, bombing, artillery, and ferocious street-by-street fighting destroyed large parts of Berlin. Berlin was subsequently divided among the four major Allied powers and for over four decades it encapsulated the Cold War confrontation between West and East. With the reunification of Germany in 1990, Berlin was restored as the capital and as a major world city.

Etymology

The name Berlin is of Slavic origin, formed from a root *berl-/*brl-, enlarged by a suffix -in which is still common in modern Slavic languages. The meaning of the root is somewhat obscure, lacking clear cognates in other languages, but usually interpreted as "bog, swamp", due to similar and obviously Slavic toponyms in Eastern Germany. As early sources mention the name with a definite article ("der Berlin"), it appears to have referred originally to a specific piece of land. Similar to other Slavic-derived German toponyms ending in -in, the name is consistently stressed on this suffix.[1][2] The name of the city's other historic kernel, Kölln, is likely derived from Cologne, called Köln in German, whose name ultimately stems from the Latin colonia "colony, new planned settlement". The prominent role of merchants from the Lower Rhine in the earliest days of the city makes this likely. A derivation from Slavic kol'no, related to a word meaning "stake, pale, post", cannot be completely excluded.[3] Contrary to folk etymology, the name is not related to bears (German sg. Bär), even though the city was allegedly founded by Albert the Bear, the first Margrave of Brandenburg. A relationship between Albert and the coat-of-arms (showing a bear) has not been reliably proven.[4]

Prehistory

The oldest human traces, mainly arrowheads, in the area of later Berlin are dating to the 9th millennium BC. During Neolithic times a large number of villages existed in the area. During the Bronze Age it belonged to the Lusatian culture. For the time around 500 BC the presence of Germanic tribes can be evidenced for the first time in form of a number of villages in the higher situated areas of today's Berlin. After the Semnones left around 200 AD, the Burgundians followed. A large part of the Germanic tribes left the region around 500 AD. In the 7th century Slavic tribes, the later known Hevelli and Sprevane, reached the region. Today their traces can mainly be found at plateaus or next to waters. Their main settlements were today's Spandau and Köpenick. No Slavic traces could be found in the city center of Berlin.[5]

Emerging city (1100–1400)

In the 12th century the region came under German rule as part of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, founded by Albert the Bear in 1157. At the end of the 12th century German merchants founded the first settlements in today's city center, called Berlin around modern Nikolaiviertel and Cölln, on the island in the Spree now known as the Spreeinsel or Museum Island. It is not clear which settlement is older and when they got German town rights. Berlin is mentioned as a town for the first time in 1251 and Cölln in 1261. The year 1237 was later taken as the year of founding as the first recorded mention of Cölln is from that year. The first mention of Berlin dates to 1244 [6] The two settlements formally merged into the town of Berlin-Cölln in 1432.[7] Albert the Bear also bequeathed to Berlin the emblem of the bear, which has appeared on its coat of arms ever since. Between 1373 and 1415, it was part of the Bohemian Crown Lands. By the year 1400 Berlin and Cölln had 8,000 inhabitants. A great town center fire in 1380 damaged most written records of those early years, as did the great devastation of the Thirty Years' War 1618–1648.[8]

Margraviate of Brandenburg (1400–1700)

In 1415, Frederick I became the elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which he ruled until 1440. Subsequent members of the Hohenzollern family ruled until 1918 in Berlin, first as electors of Brandenburg, then as kings of Prussia, and finally as German emperors. When Berlin became the residence of the Hohenzollerns, it had to give up its Hanseatic League free city status. Its main economical activity changed from trade to the production of luxurious goods for the court.

- 1443 to 1451: The first Berliner Stadtschloss was built on the embankment of the river Spree.

- At that time Berlin-Cölln had about 8,000 inhabitants. Population figures rose fast, leading to poverty.

- 1448: The inhabitants of Berlin rebelled in the "Berlin Indignation" against the construction of a new royal palace by Elector Frederick II Irontooth. This protest was not successful, however, and the citizenry lost many of its political and economic privileges.

- 1451: Berlin became the royal residence of the Brandenburg electors, and Berlin had to give up its status as a free Hanseatic city.

- In 1510: 100 Jews were accused of stealing and desecrating hosts. 38 of them were burned to death; others were banished, losing their possessions, only to be returned by later margraves.

- 1530: The Tiergarten park began when Elector Joachim I donated the property for use as a royal game preserve; it was opened to the public in the mid-17th century; it ceased being a hunting park in 1740 when the job of redesigning it in the English landscape style began.[9]

- 1539: The electors and Berlin officially became Lutheran.

- 1540: Joachim II introduced the Protestant Reformation in Brandenburg and secularized church possessions. He used the money to pay for his projects, like building an avenue, the Kurfürstendamm, between his hunting castle Grunewald and his palace, the Berliner Stadtschloss.

- 1576, Bubonic plague killed about 6,000 people in the city.

- Around 1600: Berlin-Cölln had 12,000 inhabitants.

- 1618 to 1648: The Thirty Years' War had devastating consequences for Berlin. A third of the houses were damaged, and the city lost half of its population.

- 1640: Frederick William, known as the "Great Elector", succeeded his father George William as Elector of Brandenburg. Later he initiated a policy of promoting immigration and religious toleration. Over the following decades, Berlin expanded greatly in area and population with the founding of the new suburbs of Friedrichswerder and Dorotheenstadt. During his government Berlin reached 20,000 inhabitants and became significant among the cities in Central Europe for the first time. He also developed a standing army.

- 1647: The boulevard Unter den Linden with six rows of trees was laid down between the Tiergarten park and the Palace.

- 1671: Fifty Jewish families from Austria were given a home in Berlin. With the Edict of Potsdam in 1685, Frederick William invited the French Calvinist Huguenots to Brandenburg. More than 15,000 Huguenots came, of whom 6,000 settled in Berlin. By 1687 they comprise 20% of the population, and many were bankers, industrialists and investors.[10]

- 1674 and after: The Dorotheenstadt was built in a bow of the river Spree, north-west of the Spreeinsel (Spree Island), where the Palace was situated.

- 1688 and after: The Friedrichstadt was built and settled.

- Around 1700: Many refugees from Bohemia, Poland, and Salzburg had arrived.

Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1871)

In 1701, Elector Frederick III (1688–1701) crowned himself as Frederick I (1701–1713), King in Prussia. He was mostly interested in decorum: he ordered the building of the castle Charlottenburg in the west of the city.[11] He made Berlin the capital of the new kingdom of Prussia.

- 1709: Berlin counted 55,000 inhabitants, of whom 5,000 served in the Prussian Army. Cölln and Berlin were finally unified under the name of Berlin, including the suburbs of Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt, and Friedrichstadt, with 60,000 inhabitants. Berlin and Cölln are on both sides of the river Spree, in today's Mitte borough.

On 1 January 1710, the cities of Berlin, Cölln, Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt, and Friedrichstadt were united as the "Royal Capital and Residence of Berlin".

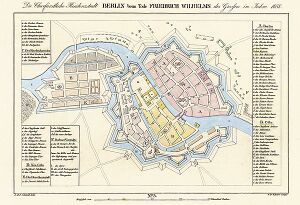

Prussian capital

As Prussia grew, so too did Berlin, and the kings made it the centerpiece of culture and the arts, as well as the Army. Under King Friedrich Wilhelm I (reigned 1713–40), Berlin's growth was encouraged by his determination to build a great military power. More men were needed, so he promoted immigration of Protestants from across Germany as well as France and Switzerland. He introduced universal primary education so that his soldiers could read and write. In 1720 he built the city's first major hospital and medical school, the Charité, now the largest teaching hospital in Europe. The city was now mainly a garrison and an armoury, for the crown heavily subsidised arms manufacturers in the capital, laying the foundations for the mechanics, engineers, technicians, and entrepreneurs who were to turn Berlin into an industrial powerhouse. The old defensive walls and moats were now useless, so they were torn down. A new customs wall (the Zoll- und Akzisemauer) was built further out, punctuated by 14 ornate gates. Inside the gates were parade grounds for Friedrich Wilhelm's soldiers: the Karree at the Brandenburg gate (now Pariserplatz), the Oktagon at the Potsdam gate (now Leipzigerplatz), the Wilhelmplatz on Wilhelmstrasse (abolished in the 1980s) and several others. In 1740, Frederick the Great (Frederick II) began his 46-year reign. He was an enlightened monarch, who patronized Enlightenment thinkers like Moses Mendelssohn. By 1755 the population reached 100,000, including 26,000 soldiers. Stagnation followed under the rule of Frederick William II, 1786–97. He had no use for the Enlightenment, but did develop innovative techniques of censorship and repression of political enemies.

- 1806: French troops marched into Berlin. Berlin was granted self-government and a far reaching military reform was started.

- 1809: The first elections for the Berlin parliament took place, in which only the well-to-do could vote.

- 1810: The Berlin University (now the Humboldt University) was founded. Its first rector was the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

- 1812: Jews were allowed to practice all occupations.

- 1814: The French were defeated in the Sixth Coalition. Economically the city was in good shape. The population grew from 200,000 to 400,000 in the first half of the 19th century, making Berlin the fourth-largest city in Europe.

- 1815: Battle of Waterloo with Prussian troops from Potsdam and Berlin participating. Berlin becomes part of the Province of Brandenburg.

- 1827: Berlin is the capital of the Province of Brandenburg from 1827 to 1843.

- 1848: As in other European cities, 1848 was a revolutionary year in Berlin. Frederick William IV (1840–1861) managed to suppress the revolution. One of his reactions was to raise the income condition to partake in the elections, with the result that only 5% of the citizens could vote. This system would stay in place until 1918.

- 1861: German Emperor Wilhelm I (1861–1888) became the new king. In the beginning of his reign there was hope for liberalization. He appointed liberal ministers and built the city hall, Das Rote Rathaus. The appointment of Otto von Bismarck ended these hopes.

Economic growth

Prussian mercantilist policies supported manufacturing enterprises and Berlin had numerous small workshops. Lacking waterpower, Berlin entrepreneurs were early pioneers in the use of steam engines after 1815. Textiles, clothing, farm equipment, railway gear, chemicals and machinery were especially important; electrical machinery became important after 1880. Berlin's central position after 1850 in the fast-growing German railway network facilitated the supply of raw materials and distribution of manufactures. As the administrative role of the Prussian state grew, so did the highly efficient, well-trained civil service. The bureaucracy and military expanded even faster when Berlin became the capital of unified Germany in 1871. the population grew rapidly, from 172,000 in 1800, to 826,000 in 1870. In 1861, outlying industrial suburbs such as Wedding, Moabit, and several others were incorporated into the city.

Religion

By 1900 about 85% of the people were classified as Protestants, 10% as Roman Catholics and 5% as Jews. Berlin's middle and upper classes were generally devout Protestants. The working classes increasingly became secularized. When workers moved to Berlin the Protestants among them largely abandoned the religious practices of their old villages. The labor unions promoted anticlericalism, and denounced the Protestant churches as aloof from the needs of the working class. However, the Catholic workers remained somewhat closer to their traditional churches, which featured liturgies that were more appealing to workers than wordy intellectual sermons at the Protestant churches. Adult attendance at Sunday church services in the early 20th century was 6% in Berlin, compared to 22% in London and 37% in New York.[12]

Berlin Romanticism

The phase of German Romanticism after Jena Romanticism is often called Berlin Romanticism (see also Heidelberg Romanticism). Notable representatives of the movement include Friedrich Schleiermacher, Wilhelm von Humboldt and Alexander von Humboldt.[13]

German Empire (1871–1918)

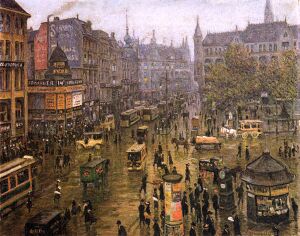

Imperial capital

After the quick victory of an alliance of German states over France in the 1870 war, the German Empire was established in 1871. Bismarck had fought and succeeded in leaving out Austria, Prussia's long standing competitor, and Prussia became the largest and by far most influential state in the new German Empire, and in turn Germany became the most powerful nation in Europe. Wilhelm I became emperor ("Kaiser"). Bismarck became Chancellor and made Berlin the center of European power politics. The imperial government and the military establishment expanded dramatically, bringing together the landed junker nobility, the rich bankers and industrialists, and the most talented scientists and scholars. In 1884 came the parliament building, the Reichstag.[14] Municipal government was handled in two parts. The ministry of police reported to the Prussian government and took control of crime, markets, and fire fighting. The civil government had a mayor appointed by the city council. It comprised 144 members elected in 48 wards by universal manhood suffrage. It handled the water supply and sanitation, streets, hospitals and charitable operations and schools.[15]

In 1870, the sanitary conditions in Berlin were among the worst in Europe. August Bebel recalled conditions before a modern sewer system was built in the late 1870s:

- "Waste-water from the houses collected in the gutters running alongside the curbs and emitted a truly fearsome smell. There were no public toilets in the streets or squares. Visitors, especially women, often became desperate when nature called. In the public buildings the sanitary facilities were unbelievably primitive....As a metropolis, Berlin did not emerge from a state of barbarism into civilization until after 1870."[16]

The primitive conditions were intolerable for a world national capital, and the Imperial government brought in its scientists, engineers and urban planners to not only solve the deficiencies but to forge the world's model city. A British expert in 1906 concluded that Berlin represented "the most complete application of science, order and method of public life," adding "it is a marvel of civic administration, the most modern and most perfectly organized city that there is."[15] In the meantime, Berlin had become an industrial city with 800,000 inhabitants. Improvements to the infrastructure were needed; in 1896 the construction of the subway (U-Bahn) began and was completed in 1902. The neighborhoods around the city center (including Kreuzberg, Prenzlauer Berg, Friedrichshain and Wedding) were filled with tenement blocks. The surroundings saw extensive development of industrial areas East of Berlin and wealthy residential areas in the South-West. In terms of high culture, museums were being built and enlarged, and Berlin was on the verge of becoming a major musical city. Berlin dominated the German theater scene, with the government-supported Opernhaus and Schauspielhaus, as well as numerous private playhouses included the Lessing and the Deutsches theatres. They featured the modern plays of Ernst von Wildenbruch, Hermann Sudermann, and Gerhart Hauptmann. who managed to work around the puritanical censorship imposed by the Berlin police.[17]

Labour unions

Berlin, with its large numbers of industrial workers by 1871 became the headquarters for most of the national labor organizations, and the favorite meeting place for labor intellectuals. Inside the city, the unions had a turbulent history. The conservative aftermath of the Revolution of 1848 drained their strength, and internal bickering was characteristic of the 1850s and 1860s. Many locals were under the control of reformist, bourgeois leaders who competed with each other and had a negative view of Marxism and socialist internationalism. They concentrated on wages, hours and control of the workplace, and gave little support to national organizations such as the Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeiterverein (ADAV) founded in 1863. By the 1870s, however, the Lassallean ADAV finally gained strength; it joined together with the Social Democratic Worker's Party (SDAP) in 1874. Henceforth the city's labor movement supported radical socialism and gained preeminence within the German labor movement. Germany had universal manhood suffrage after 1871, but the government was controlled by hostile forces, and Chancellor Otto von Bismarck tried to undermine or destroy the union movement.[18]

First World War

The "spirit of 1914" was the enthusiastic support of many of the educated middle- and upper-class elements of the population for the war when it first broke out in 1914.[19] In the Reichstag, the vote for war credits was unanimous, with all the Social Democrats joining in. One professor testified to a "great single feeling of moral elevation of soaring of religious sentiment, in short, the ascent of a whole people to the heights."[20] At the same time, there was a level of anxiety; most commentators predicted the short victorious war – but that hope was dashed in a matter of weeks, as the invasion of Belgium bogged down and the French Army held in front of Paris. The Western Front became a killing machine, as neither army moved more than a ten thousand yards at a time. There had been no preparations before the war, and no stockpiles of essential goods. Industry was in chaos, unemployment soared while it took months to reconvert to munitions productions. In 1916, the Hindenburg Program called for the mobilization of all economic resources to produce artillery, shells, and machine guns. Church bells and copper roofs were ripped out and melted down.[21] Conditions on the homefront worsened month by month, for the British blockade of Germany cut off supplies of essential raw materials and foodstuffs, while the conscription of so many farmers (and horses) reduced the food supply. Likewise, the drafting of miners reduced the main energy source, coal. The textile factories produced Army uniforms, and warm clothing for civilians ran short. The device of using replacement materials, such as paper and cardboard for cloth and leather proved unsatisfactory. Soap was in short supply, as was hot water. Morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink but using the slogan of "sharing scarcity" the Berlin bureaucracy ran an efficient rationing system nevertheless.[22] The food supply increasingly focused on potatoes and bread as it was harder and harder to buy meat. Rationing was installed, and soup kitchens were opened. The meat ration in late 1916 was only 31% of peacetime, and it fell to 12% in late 1918. The fish ration was 51% in 1916, and none at all by late 1917. The rations for cheese, butter, rice, cereals, eggs and lard were less than 20% of peacetime levels.[23] In 1917 the harvest was poor, and the potato supply ran short, and Germans substituted almost inedible turnips; the "turnip winter" of 1917–18 was remembered with bitter distaste for generations.[24] German women were not employed in the Army, but large numbers took paid employment in industry and factories, and even larger numbers engaged in volunteer services. Housewives were taught how to cook without milk, eggs or fat; agencies helped widows find work. Banks, insurance companies and government offices for the first time hired women for clerical positions. Factories hired them for unskilled labor – by December 1917, half the workers in chemicals, metals, and machine tools were women. Laws protecting women in the workplace were relaxed, and factories set up canteens to provide food for their workers, lest their productivity fall off. The food situation in 1918 was better, because the harvest was better, but serious shortages continued, with high prices, and a complete lack of condiments and fresh fruit. Many migrants had flocked into Berlin to work in industry and the government ministries, which made for overcrowded housing. Reduced coal supplies left everyone in the cold. Daily life involved long working hours, poor health, and little or no recreation, as well as increasing anxiety for the safety of loved ones in the Army and in prisoner of war camps. The men who returned from the front were those who had been permanently crippled; wounded soldiers who recovered were sent back to the trenches.[25]

Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

At the end of World War I, monarchy and aristocracy were overthrown and Germany became a republic, known as the Weimar Republic. Berlin remained the capital but faced a series of threats from the far left and far right. In late 1918 politicians inspired by the Communist Revolution in Russia founded the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, KPD). In January 1919 it tried to seize power in the Spartacist revolt. The coup failed and at the end of the month right-wing Freikorps forces killed the Communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. In March 1920 Wolfgang Kapp, founder of the right-wing German Fatherland Party (Deutsche Vaterlands-Partei), tried to bring down the government. The Berlin garrison chose his side, and the government buildings were occupied (the government had already left Berlin). A general strike stopped the putsch being successful. On October 1, 1920: The Greater Berlin Act created "Greater Berlin" (Groß-Berlin) by incorporating several neighboring towns and villages like Charlottenburg, Köpenick or Spandau from the Province of Brandenburg into the city; Berlin's population doubled overnight from about 2 to nearly 4 million inhabitants. In 1922: The foreign minister Walther Rathenau was assassinated in Berlin, and half a million people attended his funeral. The economic situation was bad. Germany owed reparation money after the Treaty of Versailles. The sums were reduced and paid using loans from New York banks. In response to French occupation, the government reacted by printing so much money that inflation was enormous. Especially pensioners lost their savings; everyone else lost their debts. At the worst point of the inflation, one dollar was worth about 4.2 trillion marks. From 1924 onwards the situation became better because of newly arranged agreements with the allied forces, American help, and a sounder fiscal policy. The heyday of Berlin began. It became the largest industrial city on the continent. People like the architect Walter Gropius, physicist Albert Einstein, painter George Grosz and writers Arnold Zweig, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Tucholsky made Berlin one of the major cultural centers of Europe. Brecht spent productive years in Weimar-era Berlin (1930–1933) working with his ‘collective’ on the Lehrstücke. Nightlife bloomed in 1920s Berlin. In 1922 the railway system that connected Berlin to its neighboring cities and villages was electrified and transformed into the S-Bahn, and a year later Tempelhof airport was opened. Berlin was the second biggest inland harbor in the country. All this infrastructure was needed to transport and feed the over 4 million Berliners. Before the 1929 crash, 450,000 people were unemployed. In the same year, the Nazi Party won its first seats in the city parliament. Nazi Propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels became Gauleiter (party district leader) of Berlin in 1926. On July 20, 1932, the Prussian government under Otto Braun in Berlin was dismissed by presidential decree. The republic was nearing its breakdown, under attack by extreme forces from the right and the left. On January 30, 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

Nazi Germany (1933–1945)

By 1931, the Great Depression had severely damaged the city's economy. Politics were in chaos, as militias controlled by the Nazis and the Communists fought for control of the streets. President Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor in January 1933, and the Nazis quickly moved to take complete control of the entire nation. On February 27, 1933, a left-wing radical was alleged to have set afire the Reichstag building (a fire which was later believed to have been set by the Nazis themselves); the fire gave Hitler the opportunity to set aside the constitution. Tens of thousands of political opponents fled into exile or were imprisoned. All civic organizations, except the churches, came under Nazi control. Around 1933, some 160,000 Jews were living in Berlin: one third of all German Jews, 4% of the Berlin population. A third of them were poor immigrants from Eastern Europe, who lived mainly in the Scheunenviertel near Alexanderplatz. The Jews were persecuted from the beginning of the Nazi regime. In March, all Jewish doctors had to leave the Charité hospital. In the first week of April, Nazi officials ordered the German population not to buy from Jewish shops. The 1936 Summer Olympics were held in Berlin and used as a showcase for Nazi Germany (though the Games had been given to Germany before 1933). In order to not alienate the foreign visitors, the "forbidden for Jews" signs were temporarily removed. Nazi rule destroyed Berlin's Jewish community, which numbered 160,000 before the Nazis came to power. After the pogrom of Kristallnacht in 1938, thousands of the city's Jews were imprisoned. Around 1939, there were still 75,000 Jews living in Berlin. The majority of German Jews in Berlin were taken to the Grunewald railway station in early 1943 and shipped in stock cars to death camps such as the Auschwitz, where most were murdered in the Holocaust. Only some 1200 Jews survived in Berlin by hiding. Approximately 800 Jews survived in Berlin's Jewish Hospital. Causes for their survival include bureaucratic infighting, hospital director Dr. Walter Lustig's relationship with Adolf Eichmann, the Nazis' bizarre system for classifying persons of partly Jewish ancestry, German leader Adolf Hitler's ambivalence about how to handle Jews of German descent, and the fact that the Nazis needed a place to treat Jews.[26] Thirty kilometers (19 mi) northwest of Berlin, near Oranienburg, was Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where mainly political opponents, Jews, Poles, Russian prisoners of war, etc. were incarcerated. Tens of thousands died there. In Berlin, Sachsenhausen had 17 subcamps for men and women, including teenagers, near industries, where the prisoners had to work. The prisoners were of various nationalities, including Polish, Jewish, French, Belgian, Czechoslovak, Russian, Ukrainian, Romani, Dutch, Greek, Norwegian, Spanish, Luxembourgish, German, Austrian, Italian, Yugoslavian, Bulgarian, Hungarian.[27] There was also a camp for Sinti and Romani people (see Romani Holocaust),[28] and the Stalag III-D prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs of various nationalities.

Nazi plans

In the late 1930s Hitler and his architect Albert Speer made plans for the new Berlin—a world city or Welthauptstadt Germania.[29] All the projects were to be of gigantic size. Adjacent to the Reichstag, Speer planned to construct the Volkshalle (The People's Hall), 250 m high, with an enormous copper dome. It would be large enough to hold 170,000 people. From the People's Hall, a southbound avenue was planned, the Avenue of Victory, 23 m wide and 5.6 kilometers (3.5 mi) long. At the other end there would have been the new railway station, and next to it Tempelhof Airport. Halfway down the avenue there would have been a huge arch 117 m high, commemorating those fallen during the world wars. With the completion of these projects (planned for 1950), Berlin was to be renamed "Germania."[30] The war postponed all construction, as the city instead built giant concrete towers as bases for anti-aircraft guns. Today only a few structures remain from the Nazi era, such as the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (National Ministry of Aviation), Tempelhof International Airport, and Olympiastadion. Hitler's Reich Chancellery was demolished by Soviet occupation authorities.

Second World War

Initially Berlin was at the extreme range of British bombers and attacks had to be made in clear skies during summer, increasing the risk to the attackers. Better bombers came into service in 1942 but most of the British bombing effort that year was spent in support of the Battle of the Atlantic against German submarines.

- 1940: A token British air-raid on Berlin on 25 August 1940; Hitler responds by ordering the Blitz on London.

- 1943: Polish resistance group Zagra-Lin successfully carries out a series of small bomb attacks.[31]

- 1943: The USAAF strategic bombing force began operations against Berlin. The RAF focused their strategic bombing efforts on Berlin in their "Battle of Berlin" from November. It was halted at the end of March 1944, after 16 mass bombing raids on the capital, due to unacceptable losses of aircraft and crew. By that point about half a million had been made homeless but morale and production was unaffected. About a quarter of the city's population was evacuated. Raids on major German cities grew in scope and raids of over 1,000 4-engined bombers were not uncommon by 1944. (On March 18, 1945 alone, for example, 1,250 American bombers attacked the city).

- 1944: USAAF bombing switched to forcing encounters with the German air force so that it could be defeated by the bombers' fighter escorts. Attacks on Berlin ensured a response from the Luftwaffe, drawing it into a battle where their losses could not be replaced at the same rate as the Allies. RAF focus switched to preparations for the invasion of France but Berlin was still subjected to regular nuisance and diversionary raids by the RAF.

- March 1945: The RAF begins 36 consecutive nights of bombing by its fast de Havilland Mosquito medium bombers (from around 40 to 80 each night). British bombers dropped 46,000 tons of bombs; the Americans dropped 23,000 tons. By May 1945, 1.7 million people (40%) had fled.[32]

- April 1945: Berlin was the main objective for Allied armies. The Race to Berlin refers to the competition of Allied generals during the final months of World War II to enter Berlin first. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower halted Anglo-American troops on the Elbe River, primarily because the Soviets made their capture of the city a high national priority in terms of prestige and revenge. The Red Army converged on Berlin with several Fronts (Army Groups). Hitler remained in supreme command and imagined that rescue armies were on the way; he refused to consider surrender.

The Battle of Berlin itself has been well chronicled.[33]

- April 30, 1945: Hitler committed suicide in the Führerbunker underneath the Reich Chancellery. Resistance continued, though most of the city was in Soviet hands by that point.

- May 2, 1945: Berlin finally capitulated.

- Hundreds of thousands of women were subjected to rape by Soviet soldiers.[34]

Destruction of buildings and infrastructure was nearly total in parts of the inner city business and residential sectors. The outlying sections suffered relatively little damage. This averages to one fifth of all buildings, and 50% in the inner city.

West and East Germany (1945–1990)

By war's end up to a third of Berlin had been destroyed by concerted Allied air raids, Soviet artillery, and street fighting. The so-called Stunde Null—zero hour—marked a new beginning for the city. Greater Berlin was divided into four sectors by the Allies under the London Protocol of 1944, as follows:

- the American sector (210.8 km2[35]), consisting of the boroughs of Neukölln, Kreuzberg, Tempelhof, Schöneberg, Steglitz, and Zehlendorf; (see: commandants of Berlin American Sector)

- the British sector (165.5 km2[35]), consisting of the boroughs of Tiergarten, Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorf, and Spandau; (see: commandants of Berlin British Sector)

- the French sector (110.8 km2),[35] consisting of the boroughs of Wedding and Reinickendorf; (See: commandants of Berlin French Sector)

- the Soviet sector (402.8 km2)[35]), consisting of the boroughs of Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg, Pankow, Weißensee, Friedrichshain, Lichtenberg, Treptow, and Köpenick; (see: commandants of Berlin Soviet Sector).

The Soviet victors of the Battle of Berlin immediately occupied all of Berlin. They handed the American, British and French sectors (later known as West Berlin) to the American and British Forces in July 1945: the French occupied their sector later. Berlin remained divided until reunification in 1990.[36] The Soviets used the period from May 1945 to July 1945 to dismantle industry, transport and other facilities in West Berlin, including removing railway tracks, as reparations for German war damage in the Soviet Union. This practice continued in East Berlin and the Soviet occupation zone after 1945. Conditions were harsh, and hundreds of thousands of refugees from the east kept pouring in. Residents depended heavily on the black market for food and other necessities.[37] Berlin's unique situation as a city half-controlled by Western forces in the middle of the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany made it a natural focal point in the Cold War after 1947. Though the city was initially governed by a Four Power Allied Control Council with a leadership that rotated monthly, the Soviets withdrew from the council as east–west relations deteriorated and began governing their sector independently. The council continued to govern West Berlin, with the same rotating leadership policy, though now involving only France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. East Germany chose East Berlin as its capital when the country was formed out of the Soviet occupation zone in October 1949; however, this was rejected by Western allies, who continued to regard Berlin as an occupied city that was not legally part of any German state. In practice, the government of East Germany treated East Berlin as an integral part of the nation. Although half the size and population of West Berlin, it included most of the historic center. By the establishment of the Oder-Neisse line and the complete expulsion of the German inhabitants east of this line, Berlin lost its traditional hinterlands of Farther Pomerania and Lower Silesia. West Germany, formed on 23 May 1949 from the American, British, and French zones, had its seat of government and de facto capital in Bonn, although Berlin was symbolically named the de jure West German capital in West German Basic Law (Grundgesetz). West Berlin de jure remained under the rule of the Western Allies, but for most practical purposes was treated as a part of West Germany; however, the residents did not hold West German passports.[citation needed]

Blockade and airlift

In response to Allied efforts to fuse the American, French, and British sectors of western Germany into a federal state, and to a currency reform undertaken by Western powers without Soviet approval, the Soviets blocked ground access to West Berlin on 26 June 1948, in what became known as the "Berlin Blockade". The Soviet goal was to gain control of the whole of Berlin. The American and British air forces engaged in a massive logistical effort to supply the western sectors of the city through the Berlin Airlift, known by West Berliners as "die Luftbrücke" (the Air Bridge). The blockade lasted almost a year, ending when the Soviets once again allowed ground access to West Berlin on 11 May 1949.[38] As part of this project, US Army engineers expanded Tempelhof Airport. Because sometimes the deliveries contained sweets and candy for children, the planes were also nicknamed "Candy Bombers".[39]

The June 17 Uprising

With Stalin dead, the KGB chief Lavrenti Beria jockeyed for power in the Kremlin, putting forth the goal of German reunification. His plan was to set up a workers' demonstration that would allow the Kremlin to remove hardliner Walter Ulbricht and begin a program of economic concessions to the workers. The plan failed when the demonstrations assumed a mass character. The strike against poor wages and working conditions overnight became a workers' revolution for democratic rights. On 17 June, the Soviets used their tanks to restore order. This failure delayed German unification and contributed to the fall of Beria. It started when 60 construction workers building the showpiece Stalin-Allee in East Berlin went on strike on 16 June 1953, to demand a reduction in recent work-quota increases. They called for a general strike the next day, 17 June. The general strike and protest marches turned into rioting and spread throughout East Germany. The East German police failed to quell the unrest. It was forcibly suppressed by Soviet troops, who encountered stiff resistance from angry crowds across East Germany, and responded with live ammunition. At least 153 people were killed in the suppression of the uprising.[40][41] The continuation of the street "Unter den Linden" on the western side of the Brandenburg Gate was renamed Straße des 17. Juni in honor of the uprising, and 17 June was proclaimed a national holiday in West Germany. The 50th anniversary of 17 June 1953 in 2003 was marked by reflection on the role of memory in creating a national identity for a unified Germany.

Berlin Wall

Loshitzky depicts the role of the Berlin Wall as a symbol of the Cold War, détente, and the collapse of the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. She divides the history of the Wall into six major stages: the erection of the Wall (1961); the period of the "geography of fear" from the Cold War; the period of détente; the short period of glasnost and perestroika; the fall of the Wall (1989); and after the Wall.[42] On August 13, 1961, the Communist East German government started to build a wall, physically separating West Berlin from East Berlin and the rest of East Germany, as a response to massive numbers of East German citizens fleeing into West Berlin as a way to escape. The wall was built overnight with no warning. This separated families for as long as the wall was up. The East German government called the Wall the "anti-fascist protection wall". The tensions between East and West were exacerbated by a tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie on 27 October 1961. West Berlin was now a de facto part of West Germany, but with a unique legal status, while East Berlin remained part of East Germany.

The western sectors of Berlin were now completely separated from the surrounding territory of East Berlin and East Germany. It was possible for Westerners to pass from one to the other only through strictly controlled checkpoints. For most Easterners, travel to West Berlin or West Germany was no longer possible. During the Wall's existence there were around 5,000 successful escapes into West Berlin; 136 people were officially killed trying to cross (see List of deaths at the Berlin Wall) and around 200 were seriously injured. The sandy soil under the Wall was both a blessing and a curse for those who attempted to tunnel their way to West Berlin and freedom. Although it was easy to dig through quickly, it was also more prone to collapse.

When the first stone blocks were laid down at Potsdamer Platz in the early hours of August 13, US troops stood ready with ammunition and watched the wall being built, stone by stone. The US military with West Berlin police kept Berliners 300 meters away from the border. President John F. Kennedy and the United States Congress decided not to interfere and risk armed conflict. They conveyed their protest to Moscow, and Kennedy sent his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, together with Lucius D. Clay, the hero of the Airlift to the city.[43] Massive demonstrations took place in West Berlin. Almost two years later, on June 26, 1963, John F. Kennedy visited West Berlin and gave a much-acclaimed speech in front of the Schöneberg City Hall in which he said, "Ich bin ein Berliner"– "I am a Berliner". This was meant to demonstrate America's lasting solidarity with the city as a Western island in Soviet satellite territory.[44] Much Cold War espionage and counter-espionage took place in Berlin, against a backdrop of potential superpower confrontation in which both sides had nuclear weapons set for a range that could hit Germany. In 1971, the Four-Power Agreement on Berlin was signed. While the Soviet Union applied the oversight of the four powers only to West Berlin, the Western Allies emphasized in a 1975 note to the United Nations their position that four-power oversight applied to Berlin as a whole. The agreement guaranteed access across East Germany to West Berlin and ended the potential for harassment or closure of the routes. As many businesses did not want to operate in West Berlin due to its physical and economic isolation from the outside, the West German government subsidized any businesses that did operate in West Berlin.

Student movement

In the 1960s, West Berlin became one of the centers of the German student movement. West Berlin was especially popular with young German left-wing radicals, as young men living in West Berlin were exempted from the obligatory military service required in West Germany proper: the Kreuzberg district became especially well known for its high concentration of young radicals. The Wall afforded unique opportunities for social gatherings. The physical wall was set some distance behind the actual sector border, up to several meters behind in some places. The West Berlin police were not legally allowed to enter the space between the border and the wall, as it was technically in East Berlin and outside their jurisdiction: many people took the opportunity to throw loud parties in this space, with the West Berlin authorities powerless to intervene. In 1968 and after, West Berlin became one of the centers of the student revolt; in particular, the Kreuzberg borough was the center of many riots.[45]

750th anniversary

-

Logo commemorating Berlin's 750th anniversary

-

Fireworks over Berlin on January 1, 1987, in recognition of the city's 750th anniversary

-

U.S. President Ronald Reagan, speaking before Brandenburg Gate on June 12, 1987, demands the Kremlin free Berlin and "Tear down this wall!"[46]

-

Communist leader Erich Honecker speaks on October 23, 1987, in commemoration of the city's 750th anniversary.

Federal Republic of Germany (1990–today)

Reunification

The Fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 ended the 28-year-long division of Berlin. On the morning of 9 November 1989, SED member Günter Schabowski announced at a press conference that border restrictions would be lifted between East and West Berlin. Although the conditions of the press release had been intended to be only temporary, Schabowski gave the impression that all restrictions would be lifted immediately, leading to large crowds forming on the eastern side of the border. Overwhelmed by the unexpected pressure, at 11:30 PM, border guards eventually allowed crowds from East Berlin to cross the frontier at the Bornholmer Strasse crossing.[47] People of East and West Berlin climbed up and danced on the wall at the Brandenburg Gate in scenes of celebration broadcast worldwide. The checkpoints never closed again, and was soon on its way to demolition, with countless Berliners and tourists wielding hammers and chisels to secure souvenir chunks.

Capital

After the fall of Communism in Europe, on 3 October 1990 Germany and Berlin were both reunited. By then the Wall had been almost completely demolished, with only small sections remaining. Various impacts of partition on Berlin were removed in subsequent months – the ghost stations of Berlin U-Bahn were reopened and the Berlin S-Bahn which had been operated by the east German Deutsche Reichsbahn also in the west (until 1984) and consequently boycotted and neglected in the west was refurbished and traffic on the Berlin ring railway resumed along its full length in 2002. Still, many S-Bahn lines shut down during partition are not yet rebuilt as of 2020. In June 1991 the German Parliament, the Bundestag, voted to move the (West) German capital back from Bonn to Berlin. The decision was reached after 10 hours of debate. In the voting Berlin won by a narrow margin: 338 for, 320 against. Berlin once more became the capital of a unified Germany.[48] In 1999 federal ministries and government offices moved back from Bonn to Berlin, but most employees in the ministries still work in Bonn. Also in 1999, about 20 government authorities moved from Bonn to Berlin, as planned in the compensation agreement of 1994, the Berlin/Bonn Act.[49] Berlin has been targeted by terrorists on several occasions; the most severe incident being a vehicle-ramming attack in 2016 that killed 13 and injured 55.[50] The number of Arabic speakers in Berlin could be higher than 150,000. There are at least 40,000 Berliners with Syrian citizenship, third only behind Turkish and Polish citizens. The 2015 refugee crisis made Berlin Europe's capital of Arab culture.[51] However, Berlin has the largest Turkish community outside of Turkey, resulting from immigration from Turkey in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.[52] In 2022, Berlin's former Tegel airport was re-opened as a refugee center.[53] Berlin is among the cities in Germany that have received the biggest amount of refugees after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. As of November 2022, estimated 85,000 Ukrainian refugees were registered in Berlin,[54] making Berlin the most popular destination of Ukrainian refugees in Germany.[55] In April 2023, Berlin got its first conservative mayor, Kai Wegner of CDU, in more than two decades.[56] Today, Berlin has become a global city for international affairs, young business founders, creative industries, higher education services, corporate research, popular media and diverse cultural tourism.[57] Population-wise, Berlin became one of the most rapidly growing urban centers in Europe after 2010, much of which has been due to immigration.

-

Reconstructed Reichstag becomes seat of Bundestag in 1999.

-

The 2006 FIFA World Cup Final was held in Berlin.

-

A. Merkel & J. Barroso in 2007

-

Humboldt University wins the German Excellence Initiative in 2012.

-

Skyline in 2013

Land Changes of Berlin

Potsdamer Platz which had been a central traffic and commerce hub in the 1920s but heavily impacted by the wall during partition became one of Europe's biggest building sites and is now once again one of Berlin's most representative addresses.[58] The museums on Museum Island were renovated and are once again museums of world renown. The Palast der Republik, the former seat of East Germany's parliament was torn down to make way for the Humboldt Forum, a reconstruction of the former Stadtschloss (City Palace) on that site.[59] The traffic infrastructure of Berlin became another post unification priority, leading to the shutdown of Tempelhof Airport in 2008,[60] the opening of a new Berlin Hauptbahnhof in 2006,[61] and finally the long delayed opening of Berlin Brandenburg Airport in 2020 accompanied by the shutdown of Tegel Airport.[62] The Central bus station ZOB Berlin which opened in the 1960s has undergone renovations which began in 2016. The renovation was expected to last until September 2022.[63]

Historical population

Population since 1400:[needs update]

- 1400: 8,000 inhabitants (Berlin and Kölln)

- 1600: 16,000

- 1618: 10,000

- 1648: 6,000

- 1709: 60,000 (union with Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichstadt)

- 1755: 100,000

- 1800: 172,100

- 1830: 247,500

- 1850: 418,700

- 1880: 1,124,000

- 1900: 1,888,000

- 1925: 4,036,000 (1920 enlargement of the territory)

- 1942: 4,478,102

- 2003: 3,388,477

- 2007: 3,402,312

- 2012: 3,543,000

- 2018: 3,605,000

See also

- Timeline of Berlin

- History of Germany

- List of Commandants of Berlin Sectors

- List of films set in Berlin

- List of people from Berlin

References

- ↑ Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch. Berlin: De Gruyter. 2012. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-11-018908-7.

- ↑ Cobbers, Arnt (2008). Kleine Berlin-Geschichte: vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart (2nd ed.). Berlin: Jaron. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-89773-142-4.

- ↑ Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch. Berlin: De Gruyter. 2012. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-11-018908-7.

- ↑ Schwenk, Herbert (1997). Berliner Stadtentwicklung von A bis Z. Berlin: Edition Luisenstadt.

- ↑ Horst Ulrich et al., Besiedlung des Berliner Raums, in: Berlin Handbuch (Berlin 1992), pp. 127–128.

- ↑ "Berlin.de". Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ↑ Bernd Stöver (2013). Berlin: A Short History. C.H.Beck. p. 98. ISBN 978-3-406-65633-0.

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis pp 41-50

- ↑ Elizabeth Heekin Bartels, "Berlin's Tiergarten: Evolution of an Urban Park," Journal of Garden History (1982) 2#2 p143+

- ↑ Alexandra Richie, Faust's Metropolis (1998) p 55

- ↑ Rudolf G. Scharmann, Charlottenburg Palace: Royal Prussia in Berlin (2005)

- ↑ Hugh McLeod, Piety and Poverty: Working-class Religion in Berlin, London and New York 1870–1914 (1996)

- ↑ Helmut Thielicke, Modern Faith and Thought, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990, p. 174.

- ↑ Gerhard Masur, Imperial Berlin (1990)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ashworth, Philip Arthur; Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 785–791.

- ↑ Cited in David Clay Large, Berlin (2000) pp 17-18

- ↑ William Grange (2006). Historical Dictionary of German Theater. Scarecrow Press. pp. 63–4. ISBN 978-0-8108-6489-4.

- ↑ Carl E. Schorske, German social democracy, 1905–1917: The development of the Great Schism (1955)

- ↑ Schweinoch, Oliver; Scriba, Arnulf (24 November 2022). "Das "August-Erlebnis"" [The "August Experience"]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in Deutsch). Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ↑ Roger Chickening, Imperial Germany and the World War, 1914–1918 (1998) p. 14

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis pp 272-75

- ↑ Keith Allen, "Sharing scarcity: Bread rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914-1923," Journal of Social History, (Winter 1998) 32#2 pp 371-93 in JSTOR

- ↑ David Welch, Germany, Propaganda and Total War, 1914–1918 (2000) p.122

- ↑ Chickering, Imperial Germany pp 140-145

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis pp 277-80

- ↑ Daniel B. Silver, "REFUGE IN HELL: How Berlin's Jewish Hospital Outlasted the Nazis" (2004)

- ↑ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume I. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 1268–1291. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ↑ "Lager für Sinti und Roma in Berlin-Marzahn". Bundesarchiv.de (in Deutsch). Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ↑ Roger Moorhouse, "Germania," History Today (March 2012), 62#3 pp 20-25

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis, pp 470-73

- ↑ Dunkle Welten: Bunker, Tunnel und Gewölbe unter Berlin, Dietmar Arnold, Frieder Salm, page 120, 2007

- ↑ Richard Overy, The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied Air War Over Europe 1940–1945 (2014) pp 301, 304

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis, pp 547-603; A. Beevor, The Fall of Berlin (2003) excerpt; Cornelius Ryan, The Last Battle (1966) excerpt; Earl Ziemke Battle for Berlin: End of the Third Reich (1968); Karl Bahm Berlin 1945: The Final Reckoning (2001) excerpt; Peter Antill and Peter Dennis, Berlin 1945: End of the Thousand Year Reich (2005) excerpt

- ↑ A Woman in Berlin is a personal account of survival by originally-anonymous journalist Marta Hillers.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Steinberg p. 1063

- ↑ Philip Broadbent and Sabine Hake, eds. Berlin: Divided City, 1945–1989 (Berghahn Books; 2010)

- ↑ Paul Steege, Black Market, Cold War: Everyday Life in Berlin, 1946–1949 (2008)

- ↑ Daniel F. Harrington, Berlin on the Brink: The Blockade, the Airlift, and the Early Cold War (2012)

- ↑ Andrei Cherny, Candy Bombers: The Untold Story of the Berlin Airlift and America's Finest Hour (2008)

- ↑ Christian F. Ostermann; Malcolm Byrne (January 2001). Uprising in East Germany, 1953. Central European University Press. pp. 35–45. ISBN 9789639241572.

- ↑ Jonathan Sperber, "17 June 1953: Revisiting a German Revolution" German History (2004) 22#4 pp 619-643.

- ↑ Yosefa Loshitzky, "Constructing and deconstructing the wall," Clio (1997) 26#3 pp 275-296

- ↑ Daum, Kennedy in Berlin (2008), pp. 51‒57.

- ↑ Daum, Kennedy in Berlin (2008), pp. 147‒156, 223‒226.

- ↑ Richie, Faust's Metropolis (1998) pp 777-80

- ↑ Daum, Kennedy in Berlin (2008), pp. 209‒210.

- ↑ NDR Fernsehen,'Schabowskis Zettel' (in German) https://www.ndr.de/geschichte/chronologie/wende/Guenter-Schabowski-Der-Zettel-und-der-Mauerfall,schabowskiszettel100.html. Retrieved 12 May 2022

- ↑ "From Bonn to Berlin: Seventy Years of the FRG". AGI.

- ↑ "When Did Germany's Capital Move to Berlin?". ThoughtCo.

- ↑ "Aftermath of the Terror Attack on Breitscheid Platz Christmas Market: Germany's Security Architecture and Parliamentary Inquiries | George C. Marshall European Center For Security Studies". www.marshallcenter.org.

- ↑ "Berlin: Inside Europe's capital of Arab culture". Middle East Eye.

- ↑ "How Berlin Became the World's Second Turkish..." Culture Trip. 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Refugee shelter expanded at ex-airport to prepare for Ukrainian influx". euronews. 9 November 2022.

- ↑ "Berlin to create 10,000 extra beds for Ukrainian refugees – DW – 11/20/2022". dw.com.

- ↑ "Survey of Ukrainian War Refugees". Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community.

- ↑ Marsh, Sarah; Rinke, Andreas; Marsh, Sarah (27 April 2023). "Berlin gets first conservative mayor in more than two decades". Reuters.

- ↑ "Is Berlin an example for Australian capital cities?". DAVID CHARLES. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ "Potsdamer Platz – Panorama Point Berlin". Panoramapunkt Berlin.

- ↑ "Completed Humboldt Forum opens in Berlin – DW – 09/16/2022". dw.com.

- ↑ "Tempelhof Airport". www.europeremembers.com.

- ↑ "Berlin's New Train Station Opens After Knifeman's Rampage – DW – 05/28/2006". dw.com.

- ↑ "On 31 October 2020 Berlin Brandenburg Airport opened". Website of the Federal Government | Bundesregierung. 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "2023 Guide to Berlin Central Bus Station: Flixbus, Location, Access and Hotels – Berlin Tourist Information". 11 June 2020.

Bibliography

Published before 1945

- Ashworth, Philip Arthur; Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 785–791.

- "Berlin", Northern Germany (5th ed.), Coblenz: Karl Baedeker, 1873, OCLC 5947482; famous guidebook

- Nathaniel Newnham Davis (1911), "Berlin", The Gourmet's Guide to Europe (3rd ed.), London: Grant Richards

- Vizetelly, Henry. Berlin Under the New Empire: Its Institutions, Inhabitants, Industry, Monuments, Museums, Social Life, Manners, and Amusements (2 vol. London, 1879) online volume 2

Published Since 1945

- Bell, Kristy. The Undercurrents: A Story of Berlin (2022), cultural and literary history excerpt

- Broadbent, Philip, and Sabine Hake, eds. Berlin: Divided City, 1945–1989 (Berghahn Books; 2010), 211 pages. Essays by historians, art historians, literary scholars, and others on perceptions and representations of the city.

- Colomb, Claire. Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) 368 pp.

- Daum, Andreas W. (2008). Kennedy in Berlin. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85824-3.

- Davis, Belinda J. (2000). Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin.

- Emerson, Charles. 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War (2013) compares Berlin to 20 major world cities on the eve of World War I; pp 59–77.

- Friedrich, Thomas. Hitler's Berlin: Abused City (2012) excerpt and text search

- Gehler, Michael. Three Germanies: West Germany, East Germany and the Berlin Republic (2011) excerpt and text search

- Hake, Sabine. Topographies of Class: Modern Architecture and Mass Society in Weimar Berlin (2008)

- Harrington, Daniel F. Berlin on the Brink: The Blockade, the Airlift, and the Early Cold War (U Press of Kentucky, 2012).

- Harrison, Hope M. "Berlin and the Cold War Struggle over Germany." in The Routledge Handbook of the Cold War (Routledge, 2014) pp. 56–73.

- Harrison, Hope M. After the Berlin Wall: Memory and the making of the new Germany, 1989 to the present (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- Kellerhoff, Sven Felix. Hitlers Berlin (2005)

- Krause, Scott H., Stefanie Eisenhuth, and Konrad H. Jarausch, eds. Cold War Berlin: Confrontations, Cultures, and Identities (Bloomsbury, 2021).

- Large, David Clay. Berlin (2000) 736pp; scholarly general history since 1870

- Lees, Andrew. "Berlin and Modern Urbanity in German Discourse, 1845–1945," Journal of Urban History (1991) 17#2 pp 153–78.

- Long, Andrew. Berlin in the Cold War: Volume 2: The Berlin Wall 1959‒1961 (2021)

- MacDonogh, Giles . Berlin: A Portrait of Its History, Politics, Architecture, and Society (1999)

- McKay, Sinclair. Berlin: Life and Loss in the City That Shaped the Century (2022) excerpt, popular history 1919 to 1989.

- Moorhouse, Roger. Berlin at War: Life and Death in Hitler's Capital 1939‒1945 (2011)

- Newman, Kitty. Macmillan, Khrushchev and the Berlin Crisis, 1958–1960 (Routledge, 2007).

- Paret, Peter (1989). The Berlin Secession: Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06774-5.

- Prowe, Diethelm. "Berlin: Catalyst and Fault Line of German-American Relations in the Cold War" in The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War 1945–1968, ed. Detlef Junker, (German Historical Institute, 2004) pp 165–171.

- Richie, Alexandra. Faust's Metropolis: A History of Berlin (1998), 1168 pp scholarly history; excerpt and text search; emphasis on 20th century.

- Richter, Hedwig. "Transnational Reform and Democracy: Election Reforms in New York City and Berlin Around 19001." The Journal Of The Gilded Age And Progressive Era 15.2 (2016): 149-175. online

- Smith, Jean Edward. The defense of Berlin (1963), covers US & Britain 1945 to 1962, with emphasis on later period.

- Steinberg, S. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1950 (87 ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-27079-4.

- Stöver, Bernd (2013). Berlin: A Short History. C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-65633-0.

- Tusa, Ann. The Last Division: A History of Berlin, 1945–1989 (1997)

- Verheyen, Dirk. United city, divided memories?: Cold War legacies in contemporary Berlin (Lexington Books, 2010).

- Windsor, Philip. "The Berlin Crises" History Today (June 1962) Vol. 6, p375-384, summarizes the series of crises 1946 to 1961; online.

- Winter, Jay, and Jean-Louis Robert, eds. Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914–1919 (2 vol. 1999, 2007), 30 chapters 1200pp; comprehensive coverage by scholars vol 1 excerpt; vol 2 excerpt and text search

Guidebooks

- Maik Kopleck: PastFinder Berlin 1933–1945. Traces of German History – A Guidebook (Pastfinder). Ch. Links Verlag; 2nd Ed. 2007, 978-3861533634 (Original title: Stadtführer zu den Spuren der Vergangenheit. Also available in French: Guide touristique sur les traces du passé)

- Maik Kopleck: PastFinder Berlin 1945–1989. 2011, 978-9889978839

External links

- Vintage Berlin: The Reunited City Archived 2010-11-22 at the Wayback Machine - slideshow by Life magazine

- http://www.weimarberlin.com/ A website about Berlin during the Weimar years (1919–1933)