Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2024) |

The depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo was an event that took place in 1962, following the formation of the United Suvadive Republic, when Thinadhoo, the wealthiest island at the time was forcefully depopulated and destroyed.[1] Before the ethnic cleansing that took place on the island, there was a population of over 6,000. As many as 4,000 residents of the island were starved or killed.[2]

Background

Havaru Thinadhoo once operated 9 long-haul ships, with Gadhdhoo operating 2 ships, Nilandhoo operating 3 ships, and Dhaandhoo operating 2 ships, bringing the total to 16 ships in Huvadhu.[5] The island was renowned for its frequent trips and its wealth enabled the southern atolls of Maldives to form a nascent thalassocracy.[6]

First rebellion

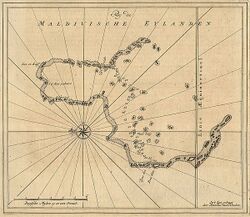

In July 1959 the southernmost atolls consisting of Huvadhu Atoll, Addu Atoll and Fuvahmulah that benefited economically from the British presence, cut ties with the Maldives government and formed an independent state, the United Suvadive Republic with Abdullah Afeef as president and Hithadhoo as its capital. This occurred after Ibrahim Nasir intended to close the RAF Gan and expel the British.[7] Ibrahim Nasir, along with army personnel, subsequently travelled to Thinadhoo on a gunboat and attacked the residents, arresting the alleged leaders of the United Suvadive Republic present at the time.[8] The United Kingdom expressed their disapproval of the Maldivian government due to the violent attack against the residents of Huvadu on August 7, 1959.[9]

Partitioning of Huvadu Atoll

After the first rebellion, Huvadhoo Atoll was partitioned into two administrative regions, Huvadu East and West, which were later renamed Huvadu South and North.[8] Today, these partitions are known as Gaafu Alifu Atoll and Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll.

Second rebellion

All photos and videos related to the incident involving Maldives Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir and Thinadhoo are connected to the first uprising. No public media has been released regarding the second uprising yet. However, it is alleged that Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir had access to videos and images that were captured during the event.[10] The second uprising began as a result of several laws enacted in the Maldives that had a significant impact on the merchants of Havaru Thinadhoo. These laws included increased tariffs and a new payment mechanism for sold items that were required to pass through the Maldives government, resulting in extended delays in payments to merchants in Havaru Thinadhoo. The new structure severely hindered the island's thriving economy.[11] Another cause of the second insurrection was the abusive behavior of Maldives government soldiers who were stationed in Havaru Thinadhoo.[11] Although additional appeals were made to the Maldives government to improve the conditions in Havaru Thinadhoo, no response was received.[11] Karankaa Rasheed, a staff member of the Maldives' People's Majlis (parliament), has stated that no such letter was ever received, and the mission to quell the insurrection was kept a state secret.[11]

Electing the leader of United Suvadive for Thinadhoo

Olha Didi and Hassan Didi, along with Muhammadh Hameed,[12] were among the individuals who were working to improve the conditions in Thinadhoo. However, when they learnt of their imminent detention by the Maldivian authorities, they were in Addu.[11] Discussions were held with Thinadhoo residents who were in Addu, and 190 individuals participated in the voting process. The purpose of the election was to re-establish the United Suvadive Republic and elect a leader from Huvadhoo to head the movement. Olha Didi and Hassan Didi won the election to head the movement, with Olha Didi receiving 140 votes.[11] Olha Didi and Hassan Didi was 19 years old at the time. Another meeting was organized in Addu with Thinadhoo residents, and according to the discussion, on the night of 5 June 1961, supporters of the United Suvadive Republic entered Thinadhoo from the Baraasil side, arrested Maldivian troops and their representatives, and took them as captives to Addu.[11] During a second meeting, Afeef Didi, the president of the United Suvadive Republic in Addu, called for the reinstatement of the United Suvadives in Huvadhoo Atoll.[11]

Turmoil in the south

The second uprising occurred with the re-establishment of the United Suvadive Republic in Thinadhoo. New legislation was passed authorizing the imprisonment, confiscation of all money, and destruction of the houses of anybody who publicly opposed the United Suvadive. The population of Huvadhoo atoll, especially Thinadhoo, was split in their support for the United Suvadive Republic but was hesitant to express their dissent owing to the law. There was internal strife in Thinadhoo before Silvercrest arrived. According to inhabitants of Gaddhoo, supporters of the United Suvadive ransacked the island, ruined its properties, and beat its residents because of their disagreement.[13]

Arrival of Silvercrest

On January 30, 1962, at around 2:30 to 3 PM, the vessel named "Silvercrest", commanded by Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir, arrived at Havaru Thinadhoo.[14] It transported soldiers equipped with five rifles and ten submachine guns.[14] Thinadhoo had constructed a sand wall called "Fasbadi" that was 400 feet long, 4 feet high, and 3 feet wide in anticipation of the arrival of Silvercrest. This bullet-proof wall was situated around the front jetty area.[15] Upon seeing Silvercrest approaching the island, Olha Didi and Hassan Didi urged the people to take cover behind the Fasbadi wall, as he anticipated that the boat might open fire towards the island as it drew closer.[16] The other senior United Suvadive representative for Thinadhoo, Muhammadh Hameed, was not present on the island at the time.[16]

Capturing of dhoani for assault

Before approaching Thinadhoo, Silvercrest chased after a dhoani[lower-alpha 1] carrying men and women who were returning to Thinadhoo after working on the neighboring island of Kaadeddhoo. It is likely that the capture of the dhoani was an attempt to use it to infiltrate Thinadhoo. When the attempt failed, Silvercrest went on to chase four more dhoanis that were returning to Thinadhoo. However, all four attempts failed, and Silvercrest fired warning shots at them, which were ignored. As a result of the gunshots, one of the dhoanis' crew members went into shock and died upon reaching Thinadhoo.[17] When Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir ordered his men to the island, some locals went into shock, vomited, and later died due to the trauma of hearing gunshots and witnessing the destruction of boats and buildings.[10] After failing to capture any of the four dhoanis, Silvercrest intercepted a dhoani approaching from the south of Kaadeddhoo and took it to Thinadhoo along with them.[17]

Shooting at Havaru Thinadhoo

After approaching the island, Silvercrest used loudspeakers to call on the people of Thinadhoo to surrender and to raise the Maldives flag instead of the United Suvadive Republic flag. Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir declared that anyone who complied with these demands would be pardoned. However, following the announcement, Silvercrest opened fire on Thinadhoo. Shocked residents watched as the leaves and branches of breadfruit trees near the Vaaruge (Tax House) splintered, and birds flew away in response to the noise.[18] The shooting resulted in the death of one person and the injury of numerous others.[10][11] Additionally, many died as a result of the shock of witnessing the violence and the subsequent forced relocation.[10]

Sending of captive to demand surrender

After the failed attempts to capture dhoanis, Zakariya Moosa, who was taken hostage from one of the boats, was brought to Thinadhoo to send another warning. He was instructed to swim to the island while holding onto a wooden plank that had been shot multiple times. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir used binoculars to watch the events from Silvercrest. Zakariya Moosa managed to reach Thinadhoo and warned the islanders to surrender and raise the Maldives flag.[18] After arriving on the island, Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir instructed Zakariya Moosa to demand Thinadhoo's surrender and to raise the Maldives flag. Thinadhoo residents and United Suvadive leaders were given the option to surrender by coming to Silvercrest, with the promise of no harm and forgiveness. Zakariya Moosa showed the damaged plank to the residents as a warning. However, while he was still delivering the message, he was seized and imprisoned by United Suvadive supporters in the Thinadhoo food store.[18]

Silvercrest anchoring for the night

Silvercrest used loudspeakers to deliver the warning, and it continued firing towards Thinadhoo until dusk that day. Following sunset, supporters of United Suvadive moved their forces inside Thinadhoo to prevent anyone from announcing their surrender.[19] After firing towards Thinadhoo until dusk, Silvercrest sailed to the nearby island of Maakiri Gala, where it anchored for the night.[19]

Messengers with word of surrender

On the morning following daybreak in Thinadhoo, Havaru Thinadhoo resident Moosa Fathuhi met with two other individuals - Abdul Wahhab from Bansaarige, who was the Secretary at the Atoll Office, and Mohamed Hussain from Maabadeyrige, who was a police officer. Moosa Fathuhi was then under house arrest. During their meeting, Moosa Fathuhi and Wahhab discussed surrender, while Mohamed Hussain attempted to persuade the remaining elders in Thinadhoo to surrender as well. However, his efforts were unsuccessful as the elders were concerned about the potential consequences of the new legislation and feared losing their possessions if they were apprehended by United Suvadive supporters. They refused to travel to Silvercrest.[20] In the evening, Abdul Wahhab and Mohamed Hussain left unnoticed by the United Suvadive Thinadhoo supporters on a small boat called Bokkura, which was headed towards Silvercrest. They were on a mission to surrender on behalf of the residents of the island, following the orders of Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir.[20] As Abdul Wahhab and Mohamed Hussain approached Silvercrest, soldiers who were preparing to fire illuminated the boat. Upon noticing them, the soldiers boarded the boat and brought them to Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir, who interrogated them. It is unclear whether the Thinadhoo residents who surrendered on their behalf were granted a pardon, as they were not informed of their status.[20] After reports surfaced about Abdul Wahhab and Mohamed Hussain's meeting on Silvercrest, United Suvadive supporters in Thinadhoo expressed hostility towards their residences. Both Wahhab and Hussain were willing to attend the meeting as they did not personally own any property in Thinadhoo.[20]

Sunrise and preparation for attack

Wahhab and Hussain transported all of the remaining prisoners, who had been captured earlier by Silvercrest, to Thinadhoo in the Bokkura. Subsequently, troops and Ibrahim Nasir's aides boarded the Dhoani, which was under their control. The Prime Minister ordered Wahhab and Hussain to board the Dhoani with the military and his subordinates.[20]

Torching of Arumaadhu Odis (large ships)

The Dhoani, accompanied by the troops and others, sailed towards Havaru Thinadhoo. As it approached the island, it set fire to a large ship called "Fathuhul Mubarak," which was anchored outside and belonged to Havaru Thinadhoo Naib Ismail Didi. Onlookers near the jetty area in Thinadhoo witnessed the burning of the ship.[15] Subsequently, all the large ships (Arumaadhu Odi) anchored on the outskirts of Thinadhoo were destroyed by fire. These included:[15]

- Arumaadhu Odi "Barakathul Rahman" owned by Mudim Hussain Thakurufaan

- Arumaadhu Odi "Fathuhul Majeed" owned by Muhammad Kaleyfaan

- Naalu Bethelli (large boat) named "Ganima" owned by Abubakuru Katheeb Kaleyfaan

- Naalu Baththeli (large boat) owned by Addu Hithadhoo Finifenmaage Abdullah Afeef

Attacking from ashore

As the Dhoani and the troops approached Thinadhoo, Abdul Wahhab and Mohamed Hussain received orders to plunge into the shallow waters and employ a rope to pull the Dhoani towards the island. Using a megaphone, the troops then demanded surrender and hoisting of the Maldive flag instead of the Suvadive flag. It was promised that forgiveness would be granted to everyone if these actions were carried out. Subsequently, submachine guns were fired into the air. Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir's directives were adhered to without hesitation.[15] As the Dhoani approached the area near Fasbadi in Havaru Thinadhoo, people from the outer wall threw stones at it. Despite the commotion, the troops persisted in firing while exhorting the populace to raise the Maldives flag.[15] At the jetty area in Havaru Thinadhoo, the flag of the United Suvadive Republic was raised atop a 40-foot-long flagpole. Upon Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir's demand for surrender, the flag was secured with a rope to prevent its easy removal.[15]

Attempt to untie the Suvadive flag

Abdul Wahhab attempted to climb the flagpole and untie the flag, but he was repeatedly pelted with stones by United Suvadive supporters, preventing him from completing the task. Meanwhile, the troops on the Dhoani continued to fire at Thinadhoo.[15] After the Dhoani and its troops reached the other side of the Fasbadi wall, the people throwing rocks at them were no longer shielded by it. They ran to a nearby school called "Madursathul Ameer Ibrahim" without the protection of the wall. Most of them stayed outside, but a few sought refuge inside the school. The leaders of the United Suvadive Republic of Thinadhoo ordered the arrest of some of the town's residents who opposed them within the school.[15]

Another messenger with word of surrender

At this point, Havaru Thinadhoo Moosa Fathuhy, a respected islander, waded into the shallow water and declared the surrender of the islanders to the Dhoani. When Annabeel Muhammadh Imaddhudheen, who was on board the Dhoani with the army, gave the command to approach, Fathuhy moved closer to the Dhoani.[15]

Assault in Thinadhoo. Burning of haruges (boat shelters)

The soldier responsible for setting fire to the ships earlier also disembarked on Thinadhoo and proceeded to set Olha Didi Katheeb, the boat shelter of Thinadhoo Katheebs, on fire. The fire consumed the Haruge completely and also destroyed the haruges of Katti Ibrahimbe and Moosa Fathuhy.[10]

Surrendering by hoisting the Maldives flag goes unheeded

After setting the Haruges on fire and firing at the island, the Dhoani headed towards the main jetty. However, they ceased firing when they noticed the Maldives flag being raised and the United Suvadive Republic flag being lowered. Ali Rasheed, a resident of Havaru Thinadhoo Diamond Villa, was responsible for this action. According to Ali Rasheed, he had attempted to lower the flag earlier, but was unable to do so due to gunfire exchanged between the "Madursathul Ameer Ibrahim" building and the location of the flagpole. Once the Dhoani and the troops left the area, he finally had the opportunity to climb the pole.[10]

Continued assault and arrival of Ibrahim Nasir to Thinadhoo

Following a brief cessation to lower the United Suvadive flag, the shooting recommenced. Shortly after, Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir arrived on Thinadhoo.[10]

Depopulation and destruction

Upon his arrival, Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir ordered the evacuation of Havaru Thinadhoo by dusk.[10][21] The command was executed by dispatching soldiers across the island.[10] During the depopulation, soldiers forced all the residents of the island, including women, children, and the elderly, to stand in shallow water up to their necks. The island was then plundered and its resources were depleted. According to survivors, many people died due to the aftermath of the incident.[22] The population of Thinadhoo was approximately 6,000, and the destruction of boats made it challenging for them to leave the island.[21] After the evacuation of the island, all the properties on the island were burned and destroyed.[10][23] After the depopulation, the Maldives government's official publication "Viyafaari Miyadhu" declared that "Havaru Thinadhoo island had no more inhabitants or houses."[24] Havaru Thinadhoo residents were subjected to imprisonment, torture, and systematic abuse, including rape.[25] Under dubious circumstances, several leaders of the United Suvadive Republic and numerous others died while in prison in Thinadhoo.[8]

Aftermath

Before its depopulation in 1959, Thinadhoo was estimated to have a population of around 6,000 people.[21] By the time relocation began on August 22, 1966, it was estimated that there were only about 1,800 individuals remaining on the island. During an event commemorating the 55th anniversary of Thinadhoo's re-population, the Mayor of Addu commented that the forced evacuation of the island's inhabitants was one of the most brutal events in Maldivian history.[26]

Transitional justice

The situation is being investigated by the Ombudsperson's Office for Transitional Justice.[27] Abdul Salaam Arif, the Chief Ombudsperson, has stated that it will be difficult to uncover the truth if the investigation into the Thinadhoo case is solely focused on its depopulation.[27] He stated that the office explored various venues for the hearing and ultimately decided to expand the scope of public testimony, noting that if the investigation solely focused on the depopulation of Thinadhoo, it would be challenging to uncover the truth.[27]

Thinadhoo council demands

The Thinadhoo Council has requested that the building previously owned by former Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir, which was seized by the state, be renamed as "GDh. Thinadhoo Velaanaage" as a form of compensation.[27] The Thinadhoo Council has made several requests, including renaming the confiscated building of former Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir as "GDh. Thinadhoo Velaanaage" as a form of restitution. Additionally, they have requested a formal apology from the state to the Thinadhoo people, the restoration of violated rights, and the seizure of 50% of income from the assets of those responsible, to be given as restitution to the Thinadhoo people for their lifetimes.[27]

Presidential apology for past actions

In a notable statement made by President Ibrahim Solih, he addressed the historical context of this depopulation, saying, "I must say, the administration treated the people like no administration should. This is something we must apologize for, even today. I apologize, as the head of government." This statement reflects an acknowledgment of the past government's actions and a commitment to addressing the issues related to the depopulation of Thinadhoo.[28]

Notes

- ↑ Boat

External links

- Abdul Haadhee Gdh, Thinandhoo . Recorded on Sept 2011. އަބްދުލް ހާދީ on YouTube

- Rasheedha Ibrahim: GDh Thinadhoo; Recorded on Sept 2011 ރަޝީދާ އިބްރާހިމް on YouTube

- Mohammed Hameed VP, Gdh Atoll Council. GDh Thinadhoo. Recorded on Sept 2011. މުހައްމަދު ހަމީދު on YouTube

- Aishath GDh Thinadhoo. Recorded on Sept 2011. އާއިޝަތު on YouTube

- Muneera, GDh Thinadhoo. Recorded on Sept 2011 .މުނީރާ on YouTube

- Aishath Didi, GDh Thinadhoo . Recorded on Sept 2011. އައިޝަތު ދީދީ on YouTube

- Ahmed Thakurufaan Kalo Beyya, GDh Thinadhoo. Recorded on Sept 2011. އަހުމަދު ތަކުރުފާނު on YouTube

- Aimina Faan, GDh Thinadhoo Recorded on Sept 2011 .އައިމިނާ ފާނު on YouTube

- Ahmedbe Kalo, GDh Thinadhoo . Recorded on Sept 2011 . އަހުމަދުބެކަލޯ on YouTube

References

- ↑ ޢަފީފު, ޢަޒީޒާ; Afeef, Azeez (17 August 2020). "އައްޒަގެ ދިރާސީ ބަސް: ސުވަދުންމަތީ މީހުންގެ ނުތަނަވަސްކަމުގެ ފެށުން". Digital repository of The Maldives National University. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28.

- ↑ UC, Press. "The Maldives: new stresses in an Old Nation".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Romero-Frias, Xavier (2016). "Rules for Maldivian trading ships travelling abroad (1925) and a sojourn southern Ceylon". Politeja (40): 67–84. JSTOR 24920196.

- ↑ Bernard, Koechlin (1979). "Notes sur l'histoire et le navire long-courrier, odi, aujourd'hui disparu, des Maldives". Archipel (in français). 18: 293. doi:10.3406/arch.1979.1516.

- ↑ ޢަފީފު, ޢަޒީޒާ; Afeef, Azeeeza (10 August 2020). "އައްޒަގެ ދިރާސީ ބަސް: ސުވަދުންމަތީ މީހުން އަރުމާދު އޮޑީގައި ކުރި ވިޔަފާރި ދަތުރު!". Digital repository of The Maldives National University. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28.

- ↑ Koechlin, Bernard (1979). "Notes sur l'histoire et le navire long-courrier, odi, aujourd'hui disparu, des Maldives". Archipel. 18: 288. doi:10.3406/arch.1979.1516.

- ↑ "The Sun never sets on the British Empire". gan.philliptsmall.me.uk. 17 May 1971. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "United Suvadive Republic". Maldives Royal Family. Archived from the original on 2002-11-01.

- ↑ "The Month in Review". Current History. 37 (218): 245–256. 1959. doi:10.1525/curh.1959.37.218.245. JSTOR 45310340.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 6" [Story of the Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo - 6]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Shafeega, Aminath (November 2009). 1950 ge aharuge thereygai dhekunuge thin atholugai ufehdhi bagaavaaiy: G. Dh havaru thinadhoo meehunge dhauru. Saruna (Thesis). Archived from the original on 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Mohammed Hameed VP, Gdh Atoll Council. GDh Thinadhoo. Recorded on Sept 2011. މުހައްމަދު ހަމީދު. Retrieved 2024-05-10 – via www.youtube.com.

- ↑ Afeef, Azeeza (2 November 2020). "އައްޒަގެ ދިރާސީ ބަސް: ސުވާދީބު ދައުލަތުގައި ހުވަދު އަތޮޅާއި ފުވައްމުލަކުގެ ބައިވެރިވުން އޮތީ ކިހާ މިންވަރަކަށް؟" [Azza's Study: What was the extent of Fuvahmulah and Havaru Atoll in the Suvadive Republic?]. Aafathis (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "ހަވަރުތިނަދޫން މީހުންބޭލުމުގެތެރެއިން - 1" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 1]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 27 September 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 5" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 5]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "ހަވަރުތިނަދޫން މީހުންބޭލި ވާހަކަ" [Story of the Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo residents]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 4 December 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 1" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 1]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 2" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 2]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 3" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 3]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "ހަވަރު ރިނަދޫ މީހުންބޭލިވާހަކަ - 4" [Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo's residents - 4]. Galehiri (in ދިވެހިބަސް). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Maloney, C (1976). "The Maldives: New Stresses in an Old Nation". Asian Survey. 16 (7): 654–671. doi:10.2307/2643164. JSTOR 2643164.

- ↑ Ali, Zueshan. "Thinadhoo revolution, bloodbath and peace" (PDF). Saruna - Maldives National University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-05.

- ↑ Lonely Planet, 1997. p. 163.

- ↑ Shafeega, Aminath (November 2009). 1950 ge aharuge thereygai dhekunuge thin atholugai ufehdhi bagaavaaiy: G. Dh havaru thinadhoo meehunge dhauru. Saruna (Thesis). Archived from the original on 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Mohamed, Ibrahim. Adaptive capacity of islands of the Maldives to climate change (PDF) (Thesis). James Cook University.

- ↑ "The depopulation of Thinadhoo was "Genocide": Addu Mayor". 11 September 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Mohamed, Naizak (Aug 10, 2022). "Thinadhoo depopulation case: Scope for testimonies from public expanded". Sun. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ↑ "Thinadhoo designated as a city". Sun. 30 August 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.