Japanese poetry

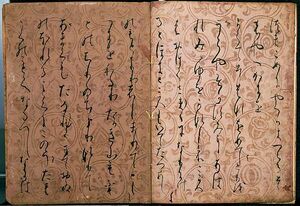

Japanese poetry is poetry typical of Japan, or written, spoken, or chanted in the Japanese language, which includes Old Japanese, Early Middle Japanese, Late Middle Japanese, and Modern Japanese, as well as poetry in Japan which was written in the Chinese language or ryūka from the Okinawa Islands: it is possible to make a more accurate distinction between Japanese poetry written in Japan or by Japanese people in other languages versus that written in the Japanese language by speaking of Japanese-language poetry. Much of the literary record of Japanese poetry begins when Japanese poets encountered Chinese poetry during the Tang dynasty (although the Chinese classic anthology of poetry, Shijing, was well known by the literati of Japan by the 6th century). Under the influence of the Chinese poets of this era Japanese began to compose poetry in Chinese kanshi); and, as part of this tradition, poetry in Japan tended to be intimately associated with pictorial painting, partly because of the influence of Chinese arts, and the tradition of the use of ink and brush for both writing and drawing. It took several hundred years[citation needed] to digest the foreign impact and make it an integral part of Japanese culture and to merge this kanshi poetry into a Japanese language literary tradition, and then later to develop the diversity of unique poetic forms of native poetry, such as waka, haikai, and other more Japanese poetic specialties. For example, in the Tale of Genji both kanshi and waka are frequently mentioned. The history of Japanese poetry goes from an early semi-historical/mythological phase, through the early Old Japanese literature inclusions, just before the Nara period, the Nara period itself (710 to 794), the Heian period (794 to 1185), the Kamakura period (1185 to 1333), and so on, up through the poetically important Edo period (1603 to 1867, also known as "Tokugawa") and modern times; however, the history of poetry often is different from socio-political history.

Japanese poetry forms

Since the middle of the 19th century, the major forms of Japanese poetry have been tanka (the modern name for waka), haiku and shi or western-style poetry. Today, the main forms of Japanese poetry include both experimental poetry and poetry that seeks to revive traditional ways. Poets writing in tanka, haiku and shi may seldom write poetry other than in their specific chosen form, although some active poets are eager to collaborate with poets in other genres. The history of Japanese poetry involves both the evolution of Japanese as a language, the evolution of Japanese poetic forms, and the collection of poetry into anthologies, many by imperial patronage and others by the "schools" or the disciples of famous poets (or religion, in the case of the Bussokusekika). The study of Japanese poetry is complicated by the social context within which it occurred, in part because of large scale political and religious factors such as clan politics or Buddhism, but also because the collaborative aspect which has often typified Japanese poetry. Also, much of Japanese poetry features short verse forms, often collaborative, which are then compiled into longer collections, or else are interspersed within the prose of longer works. Older forms of Japanese poetry include kanshi, which shows a strong influence from Chinese literature and culture.

Kanshi

Kanshi literally means "Han poetry" and it is the Japanese term for Chinese poetry in general as well as the poetry written in Chinese by Japanese poets. Kanshi from the early Heian period exists in the Kaifūsō anthology, compiled in 751.

Waka

Waka is a type of poetry in classical Japanese literature. Unlike kanshi, waka refers to poetry composed in Japanese. Waka is sometimes also used in the more specific and restrictive sense of poetry which is in Japanese and which is also in the tanka form. The Man'yōshū anthology preserves from the eighth century 265 chōka (long poems), 4,207 tanka (short poems), one tan-renga (short connecting poem), one bussokusekika (a poem in the form 5–7–5–7–7–7; named for the poems inscribed on the Buddha's footprints at Yakushi-ji in Nara), four kanshi (Chinese poems), and 22 Chinese prose passages. However, by the time of the tenth-century Kokinshū anthology, waka had become the standard term used for short poems of the tanka form, until more recent times.

Tanka

Tanka is poetry of 31 characters. It is written in the rhythm of 5-7-5-7-7 in Japanese. The tanka form has shown some modern revival in popularity. As previously stated, it used to be called waka.

Collaborative verse

Much traditional Japanese poetry was written as the result of a process of two or more poets contributing verses to a larger piece, such as in the case of the renga form. Typically, the "honored guest" composing a few beginning lines, often in the form of the hokku (which, as a stand-alone piece, eventually evolved into the haiku). This initial sally was followed by a stanza composed by the "host." This process could continue, sometimes with many stanzas composed by numerous other "guests", until the final conclusion. Other collaborative forms of Japanese poetry also evolved, such as the renku ("linked-verse") form. In other cases, the poetry collaborations were more competitive, such as with uta-awase gatherings, in which Heian period poets composed waka poems on set themes, with a judge deciding the winner(s).

Haiku

Haiku is a short verse genre written in one line in Japanese and commonly three lines in English and other languages. It has achieved significant global popularity, having been adapted from Japanese into many other languages. Typical of Japanese haiku is the metrical pattern of 5, 7, and 5 on (also known as morae). Other features include the juxtaposition of two images or ideas with a kireji ("cutting word") between them, and a kigo, or seasonal reference, usually drawn from a saijiki, or traditional list of such words. Many haiku are objective in their depiction of personal experiences.

Japanese poetry anthologies

Much of Japanese poetry has been transmitted historically through published anthologies, many of them with imperial patronage. Important collections are the Man'yōshū, Kokin Wakashū, Shin Kokin Wakashū, and the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

Early history and prehistory

The history of Japanese poetry is tied to the history of Japanese literature, that is in the purely historical sense of having extant written records. However, the early pre-history and mythology of Japan involve or include some references to poetry. And, the earliest preserved works in the Japanese language also preserve some previous poetry from this earlier period.

Mythology

According to Japanese mythology, poetry began, not with people, but with the celestial deities, the goddess Izanami and the god Izanagi. They were said to have walked around the world pillar, and encountered each other. The goddess spoke first, saying the following verse:

- What joy beyond compare

- To see a man so fair!

The male god, angry that the female had spoken first told her to go away and return later. When they again met, the male god spoke first, saying the following verse:

- To see a woman so fair—

- What joy beyond compare![1]

Chinese influence

Chinese literature was introduced into Japan ca the 6th century CE, mostly through the Korean peninsula. Just as the Chinese writing itself, Chinese literature, historical writings, religious scriptures and poetry laid the foundation for Japanese literature proper. Such influence is somewhat comparable to the influence of Latin on the European languages and literature. In the court of Emperor Tenmu (c. 631 – 686) some nobles wrote Chinese language poetry (kanshi). Chinese literacy was a sign of education and most high courtiers wrote poetry in Chinese. Later these works were collected in the Kaifūsō, one of the earliest anthologies of poetry in Japan, edited in the early Heian period. Thanks to this book the death poem of Prince Ōtsu is still extant today.[2] The strong influence of Chinese poetics may be seen in Kakyō Hyōshiki. In the 772 text, Fujiwara no Hamanari attempts to apply phonetic rules for Chinese poetry to Japanese poetry. Many of the Tang Dynasty poets achieved fame in Japan, such as Meng Haoran (Mōkōnen), Li Bo (Ri Haku), and Bai Juyi (Haku Kyo'i). In many cases, when these poets were introduced to Europe and the Americas, the source was via Japan and a Japanese influence could be seen in the pronunciations of the names of the poets, as well as the accompanying critical analysis or commentary upon the poets or their works.

Nara period

The Nara period (710 to 794) began in Japan, in 710, with the move of the Japanese capital moved from Fujiwara (today's Asuka, Nara) to Nara. It was the period when Chinese influence reached a culmination. During the Nara period, Tōdai-ji ("Great Temple of the East") was established together with the creation of the Great Buddha of Nara, by order of Emperor Shōmu. The significant waka poets in this period were Ōtomo no Tabito, Yamanoue no Okura, and Yamabe no Akahito.

Early poems recorded

The oldest written work in Japanese literature is Kojiki in 712, in which Ō no Yasumaro recorded Japanese mythology and history as recited by Hieda no Are, to whom it was handed down by his ancestors. Many of the poetic pieces recorded by the Kojiki were perhaps transmitted from the time the Japanese had no writing. The Nihon Shoki, the oldest history of Japan which was finished eight years later than the Kojiki, also contains many poetic pieces. These were mostly not long and had no fixed forms. The first poem documented in both books was attributed to a kami (god), named Susanoo, the younger brother of Amaterasu. When he married Princess Kushinada in Izumo Province, the kami made an uta, or waka, a poem.

- 八雲立つ 出雲八重垣 妻籠みに 八重垣作る その八重垣を

- Yakumo tatsu / Izumo yaegaki / Tsuma-gomi ni / Yaegaki tsukuru / Sono yaegaki wo

This is the oldest waka (poem written in Japanese) and hence poetry was later praised as having been founded by a kami, a divine creation. The two books shared many of the same or similar pieces but Nihonshoki contained newer ones because it recorded later affairs (up till the reign of Emperor Tenmu) than Kojiki. Themes of waka in the books were diverse, covering love, sorrow, satire, war cries, praise of victory, riddles and so on. Many works in Kojiki were anonymous. Some were attributed to kami, emperors and empresses, nobles, generals, commoners and sometimes enemies of the court. Most of these works are considered collectively as "works of the people", even where attributed to someone, such as the kami Susanoo.

Heian period

The Heian period (794 to 1185) in Japan was one of both extensive general linguistic and mutual poetic development, in Japan. Developments include the Kanbun system of writing by means of adapting Classical Chinese for use in Japan by using a process of annotation, and the further development of the kana writing system from the Man'yōgana of the Nara period, encouraging more vernacular poetry, developments in the waka form of poetry. The Heian era was also one in which developed an increasing process of writing poems (sometimes collaboratively) and collecting them into anthologies, which in the case of the Kokin Wakashū were given a level of prestige, due to imperial patronage.

Waka in the early Heian period

It is thought the Man'yōshū reached its final form, the one we know today, very early in the Heian period. There are strong grounds for believing that Ōtomo no Yakamochi was the final editor but some documents claim further editing was done in the later period by other poets including Sugawara no Michizane. Though there was a strong inclination towards Chinese poetry, some eminent waka poets were active in the early Heian period, including the six best waka poets.

Man'yōshū anthology

Compiled sometime after 759, the oldest poetic anthology of waka is the 20 volume Man'yōshū, in the early part of the Heian period, it gathered ancient works. The order of its sections is roughly chronological. Most of the works in the Man'yōshū have a fixed form today called chōka and tanka. But earlier works, especially in Volume I, lacked such fixed form and were attributed to Emperor Yūryaku. The Man'yōshū begins with a waka without fixed form. It is both a love song for an unknown girl whom the poet met by chance and a ritual song praising the beauty of the land. It is worthy of being attributed to an emperor and today is used in court ritual. The first three sections contain mostly the works of poets from the middle of the 7th century to the early part of the 8th century. Significant poets among them were Nukata no Ōkimi and Kakinomoto no Hitomaro. Kakinomoto Hitomaro was not only the greatest poet in those early days and one of the most significant in the Man'yōshū, he rightly has a place as one of the most outstanding poets in Japanese literature. The Man'yōshū also included many female poets who mainly wrote love poems. The poets of the Man'yōshū were aristocrats who were born in Nara but sometimes lived or traveled in other provinces as bureaucrats of the emperor. These poets wrote down their impressions of travel and expressed their emotion for lovers or children. Sometimes their poems criticized the political failure of the government or tyranny of local officials. Yamanoue no Okura wrote a chōka, A Dialogue of two Poormen (貧窮問答歌, Hinkyū mondōka); in this poem two poor men lamented their severe lives of poverty. One hanka is as follows:

- 世の中を 憂しとやさしと おもへども 飛び立ちかねつ 鳥にしあらねば

- Yononaka wo / Ushi to yasashi to / Omo(h)e domo / Tobitachi kanetsu / Tori ni shi arane ba

- I feel the life is / sorrowful and unbearable / though / I can't flee away / since I am not a bird.

The Man'yōshū contains not only poems of aristocrats but also those of nameless ordinary people. These poems are called Yomibito shirazu (よみびと知らず), poems whose author is unknown. Among them there is a specific style of waka called Azuma-uta (東歌), waka written in the Eastern dialect. Azuma, meaning the East, designated the eastern provinces roughly corresponding to Kantō and occasionally Tōhoku. Those poems were filled with rural flavors. There was a specific style among Azuma-uta, called Sakimori uta (防人歌), waka by soldiers sent from the East to defend Northern Kyushu area. They were mainly waka by drafted soldiers leaving home. These soldiers were drafted in the eastern provinces and were forced to work as guards in Kyūshū for several years. Sometimes their poetry expressed nostalgia for their faraway homeland. Tanka is a name for and a type of poem found in the Man'yōshū, used for shorter poems. The name was later given new life by Masaoka Shiki (pen-name of Masaoka Noboru, October 14, 1867 – September 19, 1902).

Kanshi in the Heian period

In the early Heian period kanshi—poetry written in Chinese by Japanese—was the most popular style of poetry among Japanese aristocrats. Some poets like Kūkai studied in China and were fluent in Chinese. Others like Sugawara no Michizane had grown up in Japan but understood Chinese well. When they hosted foreign diplomats, they communicated not orally but in writing, using kanji or Chinese characters. In that period, Chinese poetry in China had reached one of its greatest flowerings. Major Chinese poets of the Tang dynasty like Li Po were their contemporaries and their works were well known to the Japanese. Some who went to China for study or diplomacy made the acquaintance of these major poets. The most popular styles of kanshi were in 5 or 7 syllables (onji) in 4 or 8 lines, with very strict rules of rhyme. Japanese poets became skilled in those rules and produced much good poetry. Some long poems with lines of 5 or 7 syllables were also produced. These, when chanted, were referred to as shigin – a practice which continues today. Emperor Saga himself was proficient at kanshi. He ordered the compilation of three anthologies of kanshi. These were the first of the imperial anthologies, a tradition which continued till the Muromachi period.

Roei style waka

Roei was a favored style of reciting poetical works at that time. It was a way of reciting in voice, with relatively slow and long tones. Not whole poetic pieces but a part of classics were quoted and recited by individuals usually followed by a chorus. Fujiwara no Kintō (966–1041) compiled Wakan rōeishū ("Sino-Japanese Anthology for Rōei", ca. 1013) from Japanese and Chinese poetry works written for roei. One or two lines were quoted in Wakan rōeishū and those quotations were grouped into themes like Spring, Travel, Celebration.

Waka in the context of elite culture

Kuge refers to a Japanese aristocratic class, and waka poetry was a significant feature of their typical lifestyle, and this includes the nyobo or court ladies. In ancient times, it was a custom for kuge to exchange waka instead of letters in prose. Sometimes improvised waka were used in daily conversation in high society. In particular, the exchange of waka was common between lovers. Reflecting this custom, five of the twenty volumes of the Kokin Wakashū (or Kokinshū) gathered waka for love. In the Heian period the lovers would exchange waka in the morning when lovers parted at the woman's home. The exchanged waka were called Kinuginu (後朝), because it was thought the man wanted to stay with his lover and when the sun rose he had almost no time to don his clothes which had been laid out in place of a mattress (as was the custom in those days). Soon, writing and reciting Waka became a part of aristocratic culture. People recited a piece of appropriate waka freely to imply something on an occasion. In the Pillow Book it is written that a consort of Emperor Murakami memorized over 1,000 waka in Kokin Wakashū with their description. Uta-awase, ceremonial waka recitation contests, developed in the middle of the Heian period. The custom began in the reign of Emperor Uda (r. 887 through 897), the father of Emperor Daigo (r. 897 through 930) who ordered the compilation of the Kokin Wakashū. It was 'team combat' on proposed themes grouped in similar manner to the grouping of poems in the Kokin Wakashū. Representatives of each team recited a waka according to their theme and the winner of the round won a point. The team with the higher overall score won the contest. Both winning poet and team received a certain prize. Holding Uta-awase was expensive and possible only for Emperors or very high ranked kuge. The size of Uta-awase increased. Uta-awase were recorded with hundreds of rounds. Uta-awase motivated the refinement of waka technique but also made waka formalistic and artificial. Poets were expected to create a spring waka in winter or recite a poem of love or lamentation without real situations. Emperor Ichijō (980–1011) and courts of his empresses, concubines and other noble ladies were a big pool of poets as well as men of the courts. The Pillow Book (begun during the 990s and completed in 1002) and Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 978 – c. 1014 or 1025), from the early 11th century of the Heian period, provide us with examples of the life of aristocrats in the court of Emperor Ichijō and his empresses. Murasaki Shikibu wrote over 3,000 tanka for her Tale of Genji in the form of waka her characters wrote in the story. In the story most of those waka were created as an exchange of letters or a conversation. Many classic works of both waka and kanshi were quoted by the nobles. Among those classic poets, the Chinese Tang-dynasty poet Bai Juyi (Po Chü-i) had a great influence on the culture of the middle Heian period. Bai Juyi was quoted by both The Pillow Book and Tale of Genji, and his A Song of unending Sorrow (長恨歌), whose theme was a tragic love between the Chinese Emperor and his concubine, inspired Murasaki Shikibu to imagine tragic love affairs in the Japanese imperial court in her Tale of Genji.

Fujiwara no Teika

Fujiwara no Teika (1162 to 1241) was a waka poet, critic, scribe and editor of the late Heian period and the early Kamakura period. Fujiwara no Teika had three lines of descendants: the Nijō, Reizei family and Kyōgoku family. Besides that, various members of the Fujiwara family are noted for their work in the field of poetry.

Kokin Wakashū anthology

In the middle of the Heian period Waka revived with the compilation of the Kokin Wakashū. It was edited on the order of Emperor Daigo. About 1,000 waka, mainly from the late Nara period till the contemporary times, were anthologized by five waka poets in the court including Ki no Tsurayuki who wrote the kana preface (仮名序, kanajo) The Kana preface to Kokin Wakashū was the second earliest expression of literary theory and criticism in Japan (the earliest was by Kūkai). Kūkai's literary theory was not influential, but Kokin Wakashū set the types of waka and hence other genres which would develop from waka. The collection is divided into twenty parts, reflecting older models such as the Man'yōshū and various Chinese anthologies. The organisation of topics is however different from all earlier models, and was followed by all later official collections, although some collections like the Kin'yō Wakashū and Shika Wakashū reduced the number of parts to ten. The parts of the Kokin Wakashū are ordered as follows: Parts 1–6 covered the four seasons, followed by congratulatory poems, poetry at partings, and travel poems. The last ten sections included poetry on the 'names of things', love, laments, occasional poems, miscellaneous verse, and finally traditional and ceremonial poems from the Bureau of Poetry. The compilers included the name of the author of each poem, and the topic (題 dai) or inspiration of the poem, if known. Major poets of the Kokin Wakashū include Ariwara no Narihira, Ono no Komachi, Henjō and Fujiwara no Okikaze, apart from the compilers themselves. Inclusion in any imperial collection, and particularly the Kokin Wakashū, was a great honour.

Influence of Kokin Wakashū

The Kokin Wakashū is the first of the Nijūichidaishū, the 21 collections of Japanese poetry compiled at Imperial request. It was the most influential realization of the ideas of poetry at the time, dictating the form and format of Japanese poetry until the late nineteenth century. The primacy of poems about the seasons pioneered by the Kokin Wakashū continues even today in the haiku tradition. The Japanese preface by Ki no Tsurayuki is also the beginning of Japanese criticism as distinct from the far more prevalent Chinese poetics in the literary circles of its day. (The anthology also included a traditional Chinese preface authored by Ki no Tomonori.) The idea of including old as well as new poems was another important innovation, one which was widely adopted in later works, both in prose and verse. The poems of the Kokin Wakashū were ordered temporally; the love poems, for instance, depict the progression and fluctuations of a courtly love-affair. This association of one poem to the next marks this anthology as the ancestor of the renga and haikai traditions.

Period of cloistered rule

The period of cloistered rule overlapped the end of the Heian period and the beginning of the Kamakura period. Cloistered rule (Insei) refers to an emperor "retiring" into a monastery, while continuing to maintain a certain amount of influence and power over worldly affairs, and yet retaining time for poetry or other activities. During this time the Fujiwara clan was also active both politically and poetically. The period of cloistered rule mostly Heian period but continuing into the early Kamakura period, in or around the 12th century, some new movements of poetry appeared.

Imayō in the period of cloistered rule

First a new lyrical form called imayō (今様, modern style, a form of ryūkōka) emerged. Imayō consists of four lines in 8–5 (or 7–5) syllables. Usually it was sung to the accompaniment of instrumental music and dancing. Female dancers (shirabyōshi) danced to the accompaniment of imayō. Major works were compiled into the Ryōjin Hishō (梁塵秘抄) anthology. Although originally women and commoners are thought to be proponents of the genre, Emperor Go-Shirakawa was famed for his mastery of imayō.

Waka in the period of cloistered rule

Some new trends appeared in waka. There were two opposite trends: an inclination to the contemporary, modern style and on the other hand a revival of the traditional style. Both trends had their schools and won the honor to compile imperial anthologies of waka. Fujiwara no Shunzei and his son Fujiwara no Teika were the leaders of the latter school.

Renga in the period of cloistered rule

Also in this period for the first time renga were included in the imperial anthologies of waka. At that time, renga was considered a variant of waka. The renga included were waka created by two persons only, quite unlike the later style which featured many stanzas.

Kamakura period

The Kamakura period (1185–1333) is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 AD in Kamakura, by the first shōgun Minamoto no Yoritomo. The period is known for the emergence of the samurai, the warrior caste, and for the establishment of feudalism in Japan.

Shin Kokin Wakashū anthology

In the late period rule by cloistered Emperors, or the early Kamakura period (1185–1333), Emperor Go-Toba (1180–1239), who had abdicated, ordered the compilation of the eighth imperial anthology of waka, the Shin Kokin Wakashū. Go-Toba himself joined the team of editors. Other editors included Fujiwara no Teika and Kamo no Chōmei.

Later Imperial waka anthologies

The Kamakura period influence continued after the end of the actual period: after the Shin Kokin Wakashū, fourteen waka anthologies were compiled under imperial edict: the 13 Jūsandaishū (十三代集) and the Shin'yō Wakashū (c. 1381). These anthologies reflected the taste of aristocrats (and later, warriors) and were considered the ideal of waka in each period. Moreover, anthologizing served as a proof of cultural legitimacy of the patrons and often had political connotations.[3]

Nanboku-chō period

The Nanboku-chō period (1334–1392) is also known as the "Northern and Southern Courts period". Poetic movements included Renga developments, such as the publication of the Tsukubashū – the first imperial anthology of renga, in about 1356. There were various Renga poets, critics and theories, such as the development of shikimoku (renga rules) and Sōgi. Haikai no renga appears – as a parody of renga Shinseninutusukbashu. Noh play and poetry began to develop. There was influence from waka and other poetry, and Noh play reading as verse.

Renga

Renga is a collaborative verse form between two or more poets. Tsukubashū, the first imperial anthology of renga, was published in about 1356. This lent imperial prestige to this form of verse.

Sengoku period

The Sengoku period literally derives its name from the Japanese for "warring states". It was a militarily and politically turbulent period, with nearly constant military conflict which lasted roughly from the middle of the 15th century to the beginning of the 17th century, and which during which there were also developments in renga and waka poetry.

Pre-modern (Edo/Tokugawa)

In the Pre-modern or Edo period (1602–1869) some new styles of poetry developed. One of greatest and most influential styles was renku, (also known as haikai no renga, or haikai), emerging from renga in the medieval period. Matsuo Bashō was a great haikai master and had a wide influence on his contemporaries and later generations. Bashō was also a prominent writer of haibun, a combination of prose and haiku, one famous example being his Oku no Hosomichi (or, The Narrow Road to the Interior). The tradition of collaboration between painters and poets had a beneficial influence on poetry in the middle Edo period. In Kyoto there were some artists who were simultaneously poets and painters. Painters of the Shujo school were known as good poets. Among such poet-painters the most significant was Yosa Buson. Buson began his career as a painter but went on to become a master of renku, too. He left many paintings accompanied by his own haiku poems. Such combination of haiku with painting is known as haiga. Waka underwent a revival, too, in relation to kokugaku, the study of Japanese classics. Kyōka (mad song), a type of satirical waka was also popular. One poetry school of the era was the Danrin school.

Hokku

Hokku renga, or of its later derivative, renku (haikai no renga).[4] From the time of Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), the hokku began to appear as an independent poem, and was also incorporated in haibun (in combination with prose).

Haikai

Haikai emerged from the renga of the medieval period. Matsuo Bashō was a noted proponent. Related to hokku formally, it was generically different. In the late Edo period, a master of haikai, Karai Senryū made an anthology. His style became known as senryū, after his pseudonym. Senryū is a style of satirical poetry whose motifs are taken from daily life in 5–7–5 syllables. Anthologies of senryū in the Edo period collect many 'maeku' or senryū made by ordinary amateur senryū poets adding in front of the latter 7–7 part written by a master. It was a sort of poetry contest and the well written senryū by amateurs were awarded by the master and other participants.

Modern and contemporary

A new wave came from the West when Japan was introduced to European and American poetry. This poetry belonged to a very different tradition and was regarded by Japanese poets as a form without any boundaries. Shintai-shi (New form poetry) or Jiyu-shi (Freestyle poetry) emerged at this time. They still relied on a traditional pattern of 5–7 syllable patterns, but were strongly influenced by the forms and motifs of Western poetry. Later, in the Taishō period (1912 to 1926), some poets began to write their poetry in a much looser metric. In contrast with this development, kanshi slowly went out of fashion and was seldom written. As a result, Japanese men of letters lost the traditional background of Chinese literary knowledge. Originally the word shi meant poetry, especially Chinese poetry, but today it means mainly modern-style poetry in Japanese. Shi is also known as kindai-shi (modern poetry). Since World War II, poets and critics have used the name gendai-shi (contemporary poetry). This includes the poets Kusano Shinpei, Tanikawa Shuntarō and Ishigaki Rin. As for the traditional styles such as waka and haiku, the early modern era was also a time of renovation. Yosano Tekkan and later Masaoka Shiki revived those forms. The words haiku and tanka were both coined by Shiki. They laid the basis for development of this poetry in the modern world. They introduced new motifs, rejected some old authorities in this field, recovered forgotten classics, and published magazines to express their opinions and lead their disciples. This magazine-based activity by leading poets is a major feature of Japanese poetry even today. Some poets, including Yosano Akiko, Ishikawa Takuboku, Hagiwara Sakutarō wrote in many styles: they used both traditional forms like waka and haiku and new style forms. Most Japanese poets, however, generally write in a single form of poetry.

Haiku

Haiku derives from the earlier hokku. The name was given by Masaoka Shiki (pen-name of Masaoka Noboru, October 14, 1867 – September 19, 1902).

Tanka

Tanka is poetry of 31 characters. The name for and a type of poem found in the Heian era poetry anthology Man'yōshū. The name was given new life by Masaoka Shiki (pen-name of Masaoka Noboru, October 14, 1867 – September 19, 1902).

Contemporary Poetry

Japanese Contemporary Poetry consists of poetic verses of today, mainly after the 1900s. It includes vast styles and genres of prose including experimental, sensual, dramatic, erotic, and many contemporary poets today are female. Japanese contemporary poetry like most regional contemporary poem seem to either stray away from the traditional style or fuse it with new forms. Because of a great foreign influence Japanese contemporary poetry adopted more of a western style of poet style where the verse is more free and absent of such rules as fixed syllable numeration per line or a fixed set of lines. In 1989 the death of Emperor Hirohito officially brought Japan’s postwar period to an end. The category of "postwar", born out of the cataclysmic events of 1945, had until that time been the major defining image of what contemporary Japanese poetry was all about (The New Modernism, 2010). For poets standing at that border, poetry had to be reinvented just as Japan as a nation began reinventing itself. But while this was essentially a sense of creativity and liberation from militarist oppression, reopening the gates to new form and experimentation, this new boundary crossed in 1989 presented quite a different problem, and in a sense cut just as deeply into the sense of poetic and national identity. The basic grounding “postwar”, with its dependence on the stark differentiation between a Japan before and after the atomic bomb, was no longer available. Identity was no longer so clearly defined (The New Modernism, 2010) In 1990, a most loved and respected member of Japan’s avant-garde and a bridge between Modernist and Post-Modern practice unexpectedly died. Yoshioka Minoru, the very embodiment of what the postwar period meant to Japanese poetry, had influenced virtually all of the younger experimental poets, and received the admiration even of those outside the bounds of that genre (The New Modernism, 2010). The event shocked and dazed Japan’s poetry community, rendering the confusion and loss of direction all the more graphic and painful. Already the limits of “postwar” were being exceeded in the work of Hiraide Takashi and Inagawa Masato. These two poets were blurring the boundary between poetry and criticism, poetry and prose, and questioning conventional ideas of what comprised the modern in Japan (The New Modernism, 2010). Statistically there are about two thousand poets and more than two hundred poetry magazines in Japan today. The poets are divided into five groups: (1) a group publishing the magazine, Vou, under the flag of new humanism; (2) Jikon or time, with neo-realism as their motto, trying to depict the gap between reality and the socialistic ideal as simply as possible; (3) the Communist group; (4) Rekitei or progress, mixing Chinese Han poetry and the traditional Japanese lyric, and (5) Arechi or waste land (Sugiyama, 254). The Western poets who appeal to the taste of poetry lovers in Japan are principally French: Verlaine, Paul Valéry, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire; and Rainer Maria Rilke is also a favorite (Sugiyama, 255). English poetry is not very popular except among students of English literature in the universities, although Wordsworth, Shelley, and Browning inspired many of the Japanese poets in the quickening period of modern Japanese poetry freeing themselves from the traditional tanka form into a free verse style only half a century ago (Sugiyama, 256). In more recent women’s poetry, one finds an exploration of the natural rhythms of speech, often in a specifically feminine language rather than a high, literary form, as well as the language of local dialects (The New Modernism, 2010). All of these strategies are expressions of difference, whether sexual or regional, and map out shifting fields of identity in modern Japan against a backdrop of mass culture where these identities might otherwise be lost or overlooked.

List of Japanese Contemporary Poets

- Fujiwara Akiko

- Takashi Hiraide

- Toshiko Hirata

- Iijima Kōichi

- Inagawa Masato

- Park Kyong-Mi

- Sagawa Chika

- Itō Hiromi

- Wago Ryōichi

- Yagawa Sumiko

- Yoshioka Minoru

- Takagai Hiroya

See also

Various other Wikipedia articles refer to subjects related to Japanese poetry:

Anthologies

- Category:Japanese poetry anthologies

- Kaifūsō, oldest published kanshi collection

- List of Japanese poetry anthologies

- Man'yōshū, Nara period anthology

- Nijūichidaishū, 21 imperial waka anthologies

- Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, collection of 100 poems by 100 poets selected by Fujiwara no Teika

Important poets (premodern)

- Kakinomoto no Hitomaro

- Ariwara no Narihira

- Ono no Komachi

- Izumi Shikibu

- Murasaki Shikibu

- Saigyō

- Fujiwara no Teika

- Sōgi

- Matsuo Bashō

- Yosa Buson

- Yokoi Yayū

- Kobayashi Issa

Important poets (modern)

- Yosano Akiko

- Kyoshi Takahama

- Masaoka Shiki

- Taneda Santōka

- Takamura Kōtarō

- Ishikawa Takuboku

- Hagiwara Sakutarō

- Kenji Miyazawa

- Noguchi Yonejirō

- Tanikawa Shuntarō

- Ibaragi Noriko

- Tarō Naka

- Kitahara Hakushū

Influences and cultural context

- Buddhist poetry, major religious-based genre, with significant Japanese contributions

- Classical Chinese poetry, big influence on early Japanese poetry

- Japanese aesthetics

- Tang poetry, referring to poetry typical of the 618–907 poems

- Karuta, type of poetry card game

- Iroha-garuta, based in the "Iroha" poem

- Uta-garuta, generally based on the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu one-hundred waka poems

- Wabi-sabi, a Japanese world view or aesthetic

- Winter Days, multimedia (movie) version of Bashō's eponymous renku

Poetry forms and concepts

Major forms

- Haikai, includes various subgenres

- Kanshi, Chinese verse adopted and adapted in Japan

- Renga, collaborative poetry genre, the hokku (later haiku) was the opening verse

- Renku, collaborative poetry genre, genre developed from renga

- Shigin, oral recitation (chanting) of poetry in Japanese or Chinese, with our without audience

- Tanka, traditional short poetic form, related to waka

- Waka, traditional short poetic form, related to tanka

Miscellaneous forms and genres

- Death poem, poem written immediately prior to and in anticipation of the death of the author

- Dodoitsu, four lines with 7–7–7–5 "syllable" structure

- Haibun, prose-verse combined literature

- Haiga, verse-painting combined art form

- Imayō, lyrical poetry form, an early type of ryūkōka

- Iroha, a particular poem using Japanese characters uniquely and sequentially

- Kyōshi, a minor form derived from comic Chinese verse

- Renshi, modern form of collaborative verse

- Ryūka, poetry (originally songs) from the Okinawa Islands

- Senryū, haikai-derived form

- Yukar, a form of epic poetry originating in the oral tradition of the Ainu people

- Zappai, another haikai-derived form

- Gogyōshi,a style of Japanese poem that consists of a title and five lines

- Gogyōka,a five-line, untitled, Japanese poetic form.

Concepts

- Honkadori, allusive references to previous poems

- Category:Japanese literary terms, general list of Japanese literary terms, many applying to poetry

- List of kigo (saijiki), allusive phrases of seasonal connotation, often used in haiku

- On (Japanese prosody), syllabic analysis

Japanese literature

- Category:Japanese literary terms

- Monogatari

- Uta monogatari, form of monogatari emphasizing waka poems mixed with the prose

- The Tales of Ise, prime uta monogatari example

Japanese language

Reference lists

- List of Japanese poem anthologies (Japanese Literature article section "Poetry")

- List of Japanese language poets

- List of National Treasures of Japan (writings)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (writings: Chinese books)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (writings: Japanese books)

Category tree

| To display all pages, subcategories and images click on the "►": |

|---|

Notes

- ↑ Graves, 393: his translation.

- ↑ Konishi Jin'ichi. A History of Japanese Literature: The Archaic and Ancient Ages. Princeton, NJ : Princeton Univ. Pr., 1984, pp. 310–23. ISBN 978-0-691-10146-0

- ↑ Huey, Robert. (1997: 170–192) "Warriors and the Imperial Anthology" in The Origins of Japan's Medieval World: courtiers, clerics, warriors, and peasants in the fourteenth century. Ed. by Jeffrey P Mass, Stanford, Calif. : Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-2894-2. For the list of the Jūsandaishū, see the Nijūichidaishū article.

- ↑ Blyth, Reginald Horace. Haiku. Volume 1, Eastern culture. The Hokuseido Press, 1981. ISBN 0-89346-158-X p123ff.

References

- Graves, Robert (1948 [1983]). The White Goddess: Amended and Enlarged Edition. New York, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Sugiyama, Yoko. "The Waste Land and Contemporary Japanese Poetry". Comparative Literature. Vol 13, No. 3 Summer, 1961 Oregon, Duke University Presspp. 254–256 Found at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1769001> May 20, 2011

- Selland, Eric. "The Landscape of Identity: Poetry and the Modern in Japan". The New Modern. Ed. 2004. Litmus Press. Found at <http://ericselland.wordpress.com/2010/03/10/the-landscape-of-identity-poetry-and-the-modern-in-japan/> May 19, 2011

- Nakayasu, Sawako. "Contemporary Japanese Poetry in English Translation". Ed. Factorial Press. Found at <https://web.archive.org/web/20110722054625/http://www.factorial.org/Database/database.html> May 20, 2011

Works and collections

The largest anthology of haiku in Japanese is the 12-volume Bunruihaiku-zenshū (Classified Collection of Haiku) compiled by Masaoka Shiki, completed after his death, which collected haiku by seasonal theme and sub-theme. It includes work dating back to the 15th century. The largest collection of haiku translated into English on any single subject is Cherry Blossom Epiphany by Robin D. Gill, which contains some 3,000 Japanese haiku on the subject of the cherry blossom.< Gill, Robin D. Cherry Blossom Epiphany, Paraverse Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-9742618-6-7 > H. Mack Horton's translation of the 16th-century Journal of Sōchō, by a pre-eminent renga poet of the time, won the 2002 Stanford University Press Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature.< Stanford University Press Awards >

Further reading

- Miner, Earl Roy, Hiroko Odagiri, and Robert E. Morrell. (1985). The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature. Princeton :Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00825-7

- Miner, Earl Roy, and Robert H. Brower. (1968). An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0636-0; OCLC 232536106